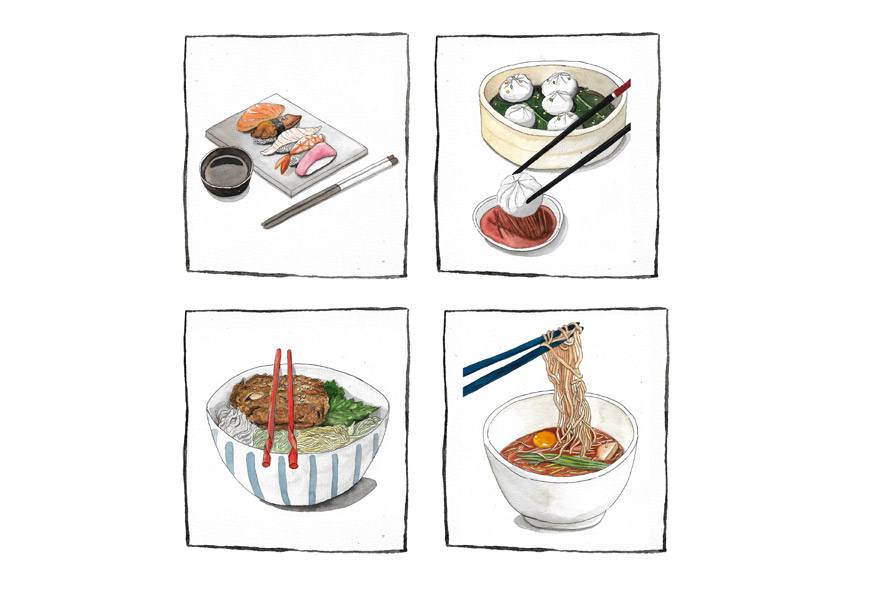

The first time you slurped a fresh oyster in a city by the sea. The juicy mango that stains your chin and your t-shirt every summer. The taste of a cold, refreshing beer on a hot, carefree holiday. Food memories have the power to transport you back in time to a specific moment.

Chef Anumitra Ghosh Dastidar puts these memories down as an ‘edible archive’. “When we eat something, it enters our edible archive,” she says, when we meet her at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Anumitra, who also has a PhD in Cognitive Linguistics, refers to a concept of how ideas get stored in the mind and body. It’s the edible archive — which each of us carries — that determines how you react to a food you enjoy or despise even 10 years after you first tasted it.

It’s this concept that sparked Edible Archives — a project that spotlights indigenous rice — which Anumitra has curated with caterer and author Prima Kurien for the Biennale. “I have eaten [a lot of] rice so there are all these entries in my edible archive,” Anumitra says. With the project, she uses her own experiences — gathered during her years as a chef at Diva in Delhi, in Japanese, Thai and Italian restaurants in Southeast Asia, South Africa and India, and on her travels — to serve wholesome meals centred around a single variety of indigenous rice. Visitors partaking of the experience end up having the meal entering their own edible archive, thereby creating a collective, shared edible archive. Shalini Krishan, an editor who’s also part of the Edible Archives team, explains that the space functions as a food lab of sorts as well. “Chefs can come from different parts of the country and cook with rice that they’ve never seen before,” she says. “So, with a particular rice, which might be typically used in a temple or for a sweet dish, someone may decide that they want to cook pork with it or they want to make papad out of it.”

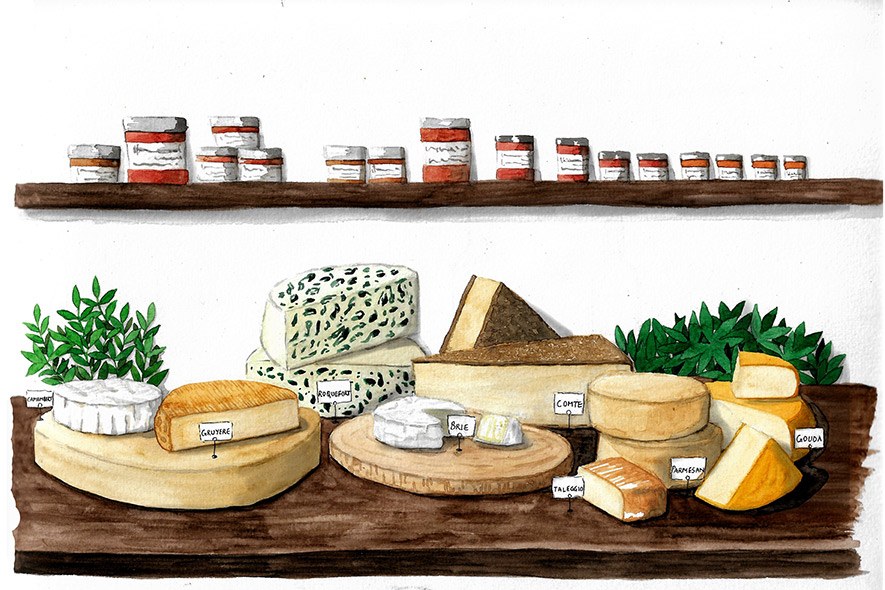

As Indians, rice is almost a part of our DNA. But in the last 60-odd years, there have been significant shifts in our consumption of rice. Where there were once numerous indigenous varieties across the country, markets today stock homogenised grains. What’s also fairly problematic is the kind of rice that has come to be popular. Growing basmati, for instance, involves a lot of groundwater. “If you think about what it’s doing to the environment, it’s very interesting and scary,” explains Anumitra. “It’s not a rain-fed rice, so as long as you’re having it in small quantities, it’s perfectly fine. But after globalisation, there was a middle-class boom, where the disposable income went up, and all the ‘special’ things were not special anymore. It became everyday because you could afford it. We forget that this has an effect on the environment too.”

Even when local varieties are popular, there are distinct favourites as well, Anumitra points out. In Mumbai, for instance, there’s a big market for surti kolam. In Bengaluru, on the other hand, sona masuri is common. Comparatively, even though there are numerous varieties, only about a dozen reach the cities.

When it comes to cooking for herself, Anumitra keeps it simple. While friends have described her house as an “ingredient museum”, it’s fragrant white rice that bags the comfort-food honour for her. She rattles off names of small-grain scented rice varieties that make the cut — gobindobhog, ambemohar, seeraga samba, radhatilak, kalonunia — and explains that it’s a meal of cooked rice, lightly blanched seasonal vegetables, very good ghee, salt and green chilli, with perhaps, a fried fish.

By the time the Biennale is over, Anumitra expects to have cooked around 30 indigenous varieties of rice, a feat considering how rare some of these grains are. The project has been using single-origin rice, which is grains sourced from one specific farm. Among the many kinds that have been showcased is thavala kannan from Wayanad, which blooms open like a frog eye, as well as pokkali (grown in the coastal regions of central Kerala), which is almost entirely flood resistant.

At Edible Archives, you can choose a vegetarian meal or add in a non-veg component — both come neatly plated in a clay pot. It’s simple fare, that’s high on flavour and lets the ingredients shine, something that Anumitra is conscious of as well. “Whatever ingredient I work with, I first try to understand what the traditional way of cooking it is. If something is traditionally done in a certain way, there is thousands of years of history behind it, and I can’t deny that,” she says. “I don’t use much spices, I don’t overdo anything. Whatever ingredient you’re tasting, you have to take the memory of that ingredient with you,” she says.

Edible Archives is at the Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018-19. Cabral Yard, Fort Kochi. Until March 29. Follow the project on Instagram here.

Fabiola Monteiro is Senior Editor at Paper Planes. She’s on Instagram at @fabiolamonteiro and on Twitter at @thefabmonteiro.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.