Chennai has always been home. Moving away for college came with having to confront change, but my campus in Sonipat, Haryana, offered a sense of security and protection. On my trips home, I began to feel a disorienting uneasiness, which loomed larger when I returned to the city for my internship. Slowly, I found solace in work; my internship involved learning and writing about heritage in Chennai. I would go for early morning heritage walks around some of the most pleasing areas in the city, soaking in its wondrous art and history.

The walks were mostly attended by students, couples vacationing in the city, and heritage enthusiasts. One of the walks we went on was along Kamarajar Salai, a road running parallel to the Marina Beach. The road comprises an array of historically relevant structures such as the All India Radio premises and the office of the Director-General of Police, and is considered the cradle of Indo-Saracenic architecture. The style is a unique amalgamation of Islamic and Hindu elements, and the buildings we explored on our walk included Presidency College, the Public Works Department, Chepauk Palace and the Senate House, in that order. While each has its own enthralling story, they are tied together by a clutch of common architectural features. In India, colonial architecture began its revolution in the 1750s by establishing governmental and public embellishments in order to substantiate the Crown’s authority.

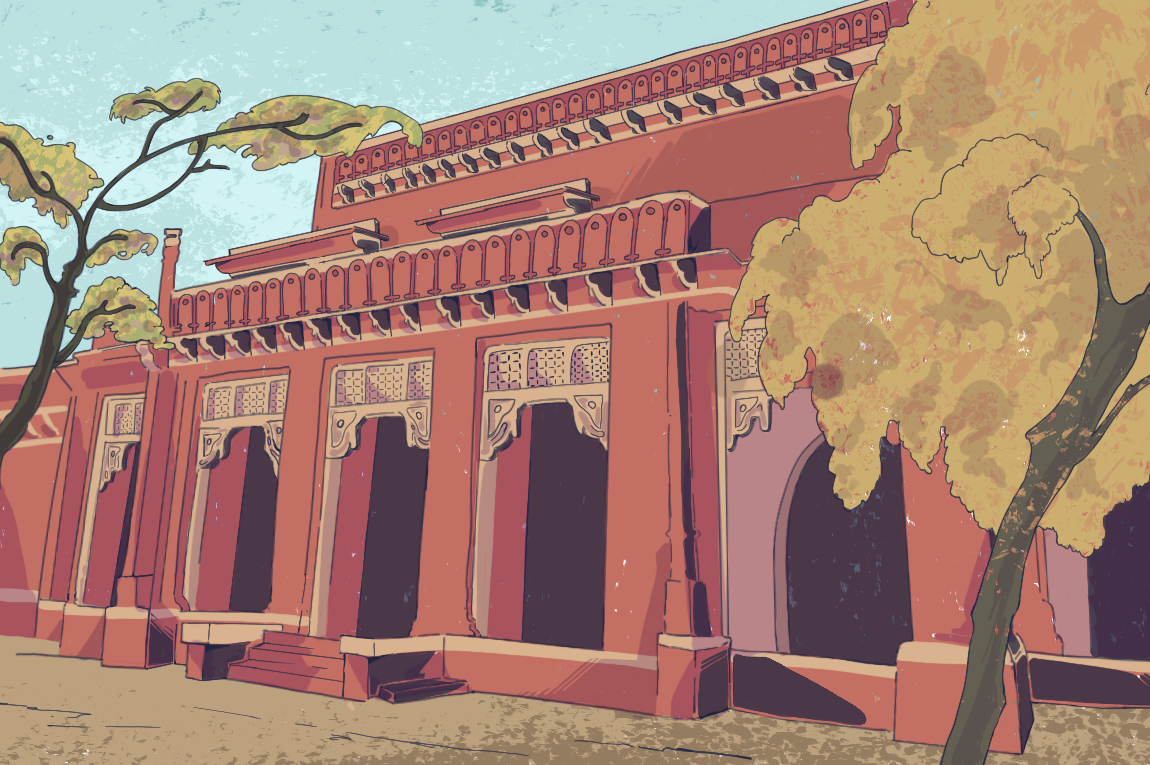

Ashmitha Athreya, Head of Operations at Madras Inherited — an initiative working towards generating awareness about the city’s history and heritage — explained to me how proximity to the port made the Marina an ideal location to build structures that would leave a lasting impression upon traders and merchants. The buildings were planned so that the power and influence of the Raj shone through. This led to the birth of the Indo-Saracenic style, evocative of a bygone era, characterised by classic red bricks, minarets, turrets, arches and majestic staircases.

The Senate House, located towards the northern end of the Marina beach, was built to function as the administrative hub of the University of Madras, and designed by British architect Robert Chisholm. Construction was completed in the late 1870s. It consists of four towers decorated with stained glass, walls painted in earthy tints, a convocation hall, and meeting rooms with high ceilings and porticos. Brick shells and lime mortar were carefully procured to make roofs with exquisite designs. The premises, however, are currently not in use.

The Public Works Department of Tamil Nadu, a five-minute walk from the Senate House, is also one of Chisholm’s constructions, initiated by Lord Dalhousie in 1858. Over the years, the Department has smoothly kept in pace with ever-changing structural and organisational overhauls. The portion of the building facing the Chepauk Palace has borrowed from European components, while the side facing the coast mirrors temple architecture. Sharp sunshades, verandah arches and wooden jaalis were adopted to suit the climate in south India, further substantiating styles that represented a confluence of cultures.

In 1864, Chisholm, then a young architect, won a design competition, landing him the opportunity to significantly shape the face of Madras by building the Presidency College. As an affirmation of the ideologies of the government, architectural historian Philip Davies, in his 1985 book Splendours of the Raj, describes the Presidency College as having been designed to sympathise with the nearby Chepauk Palace, and Chisholm’s Senate House as “a more ambitious Saracenic exercise.” Regardless, chunam, a fine plaster, was used to cement the interiors of the edifice of the college, which was opened in 1870.

Lastly, the structure that undoubtedly lent momentum to the Indo-Saracenic style in Madras is the Chepauk Palace, home to the nawabs of the Carnatic. The oldest among these establishments and the most dramatic, it was built by an engineer, Paul Benfield, in 1768, and is said to be the first Indo-Saracenic building of India. The splendours of the palace are upheld by four different facets — Humayun Mahal, Dhiwani Khana, Naubat Khana and Khalsa Mahal. The palace is undergoing restoration according to Ashmitha, and will hopefully be open to the public thereafter.

As I quietly observed the morning sunlight on the classic red brick walls, nothing felt amiss. In the grand scheme of things, it is a miracle that these buildings continue to survive. Their grandiose makes my problems feel tiny and fixable, and all of this was perhaps some reassurance that Chennai doesn’t have to be a city I run away from.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Neeraja Srinivasan is currently studying English and Creative Writing at Ashoka University. She is on Instagram at @neerajaaaaaa.