Apart from the undoubtedly delectable cuisine, my hometown Hyderabad has a lot to offer. A spot I would recommend any visitor to make time for is the Telangana Mahila Viswavidyalayam — formerly and popularly known as University College for Women — in Osmania University. I pass by it regularly, and on each occasion, I make my way through the bustle, owing to its busy location in Koti — a hub for small businesses — where bookstores selling used books attract crowds of students. As I meander through a tree-laden path in the campus, I spot the building that was once the British Residency, but now houses the educational institute for women.

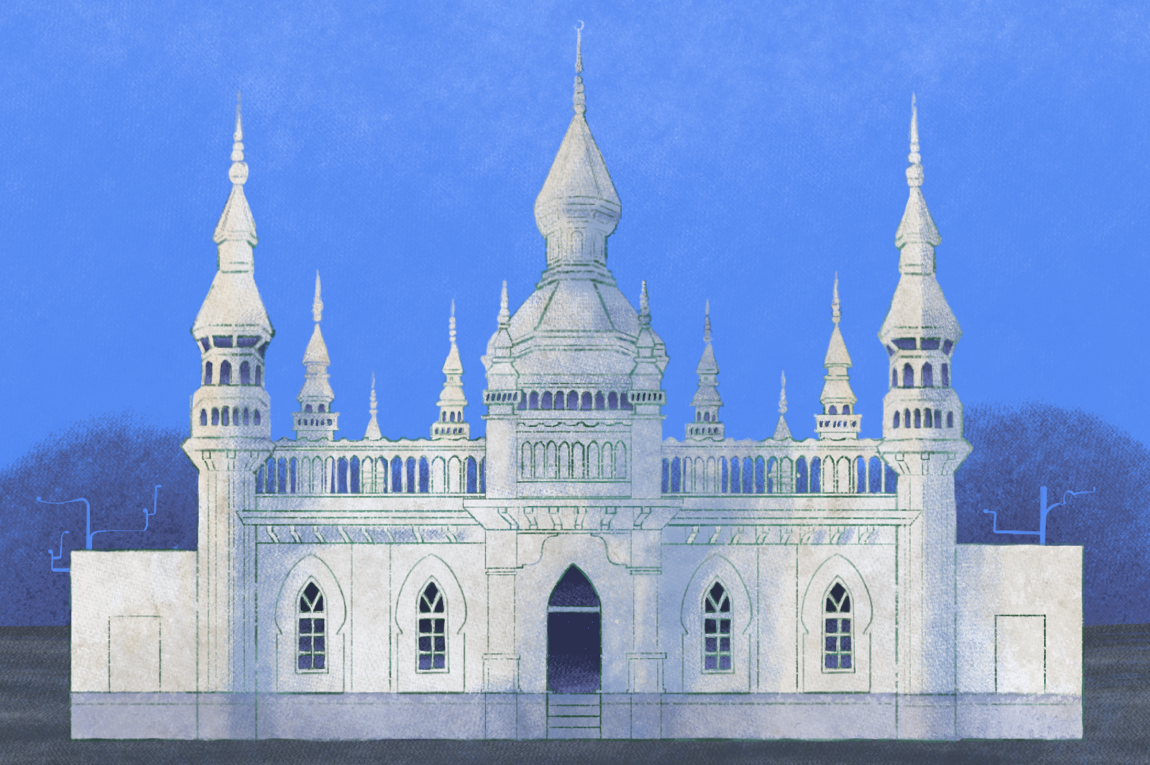

The British Residency was built after the Nizams and the British signed the Subsidiary Alliance treaty in 1798, which formally allowed the British to station their troops in Hyderabad. As part of their Residency system, the British would place Residents — agents of indirect rule — in Indian states. The then British Resident in Hyderabad and an officer of the East India Company, James Achilles Kirkpatrick, wished to build a grand Residency, and consulted Lt Samuel Russell of the Madras Engineers to design it. It is believed to have been built between 1803 and 1806 under the supervision of Kirkpatrick at a cost covered by Nizam Ali Khan, Asaf Jah II. Its Palladian style of architecture not only established a powerful representation of the British rule in Hyderabad, but also suited Kirkpatrick’s lifestyle. Its southern facade faces the Musi River — I can only imagine how lovely it would have been to stroll around there back then.

Kirkpatrick is also remembered for his love for a Hyderabadi noblewoman, Khair un-Nissa, who he later married. Historian William Dalrymple’s 2002 book White Mughals narrates the tale of the scale model of the Residency at the back of the complex — it is believed to have been built by Kirkpatrick as a token of his love for Khair un-Nissa. She lived in her bibi ghar (women’s house) separately under the purdah system — which segregated men and women — disallowing her to explore the Residency as a whole. The model was Kirkpatrick’s way of presenting the building to her in its entirety.

As I stand in front of the structure, I am struck by the opulence of the 21 marble stairs flanked by two lions on either side, which lead to 40-feet-high Corinthian pillars and the porch. I find it difficult to imagine that it was in a state of ruin nearly two decades ago, after which the World Monuments Fund worked to restore it. It only became accessible to the public early last year, in January 2023.

The facade is truly stunning — as the intricate stucco patterns draw my attention, I also notice the British Royal Coat of Arms on the pediment at the entrance. According to conservation architect B Sarath Chandra, who worked on restoring the Residency, the typical features of the Palladian style of architecture can be seen in the elevated plinth, grand flight of steps, colonnade of pillars with Doric and Corinthian columns supporting the crown cornice and pediment, and the spatial organisation of the building. Lime plaster and mud mortar were used as native building materials, alongside traditional Indian craft techniques. This facade resembles not only the Government House in Kolkata, but also the White House in Washington DC, owing to similar architectural styles.

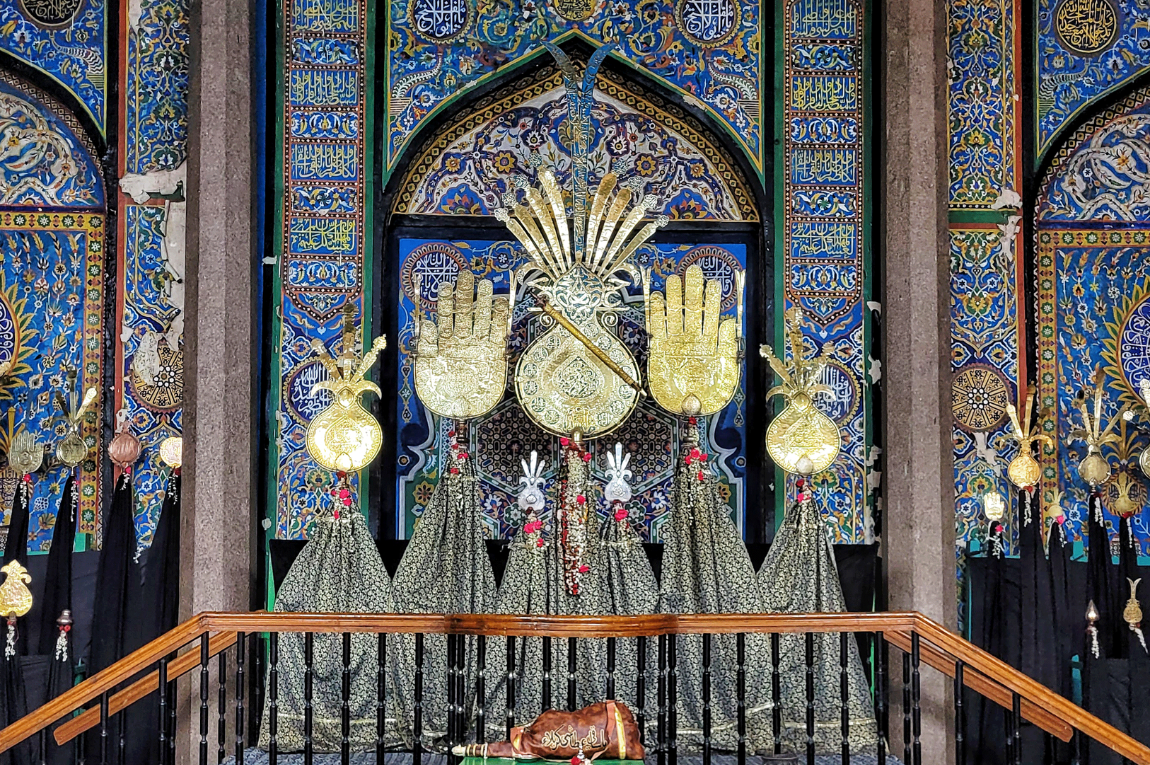

I step into what I regard as the Residency’s main draw — and a prominent location in White Mughals — the Durbar Hall. It features Burmese teakwood flooring, and chandeliers that are believed to have been imported from London. The papier mache ceiling in the hall, which was beautifully repaired over two years, is a sight to behold. Sarath tells me that the original ceiling was most probably done in the late Victorian period, and mostly manufactured in England before it was assembled at site, and that perhaps, it is the only such ceiling of this scale in India. “We used different strategies ranging from authentic reconstruction, high-definition digital printing, original process of fixing the papier mache panels to the suspended wooden truss, etc,” he says as he explains his restoration strategies.

The British Residency stands tall with an imposing shadow against the local landscape — it reminds me of the foreign rule that subsequently shaped many aspects of India, which continue to reflect across the city even today.

Find your way to the former British Residency in Hyderabad via Google Maps here.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Kavitha Yarlagadda is an independent journalist based in Hyderabad. She is passionate about writing, sustainability and nature, and likes to write about social and environmental issues. She is on Instagram at @kavithawrites.