Over a year ago, on a cold winter night in the quaint, hippie village of Dharamkot in Himachal Pradesh, I had my first tête-à-tête with the Lego-like structures of the Himalayas. It was December 31, and with a bunch of strangers who were as hopeful about the new year as I was, we ushered in 2022 at my friend Nidhi’s rented stone-and-wood house, which was set for demolition. The temperature neared zero degrees, but inside, the house was astoundingly warm, with high-spirited drunken belly laughs filling the air. In a rather emotional moment, Nidhi expressed disdain for her landlord, who was going to pull the house down to make way for a concrete building instead — a bed-and-breakfast space that would bring him big money.

Thanks to a writing project, I soon landed the opportunity to learn more about this dying Himalayan architectural technique called kath kuni. The term is derived from two Sanskrit words — kashtth meaning ‘wood’ and kona meaning ‘corner’. Owing to their cementless construction, one might assume that kath kuni houses are flimsy, but history reveals otherwise.

Kath kuni structures have sheltered Himachalis from the rain, wind, sun, landslides and earthquakes for centuries. The construction can be spotted in a variety of buildings — from ancient castles (the popular Naggar Castle in Kullu, for instance) and temples, to darbargadhs (old royal residences) and kots (forts), to residential dwellings and granaries. Meander around Kullu–Manali, Tirthan, Chamba or Shimla, and you’ll see several kath kuni structures set against exquisite natural landscapes.

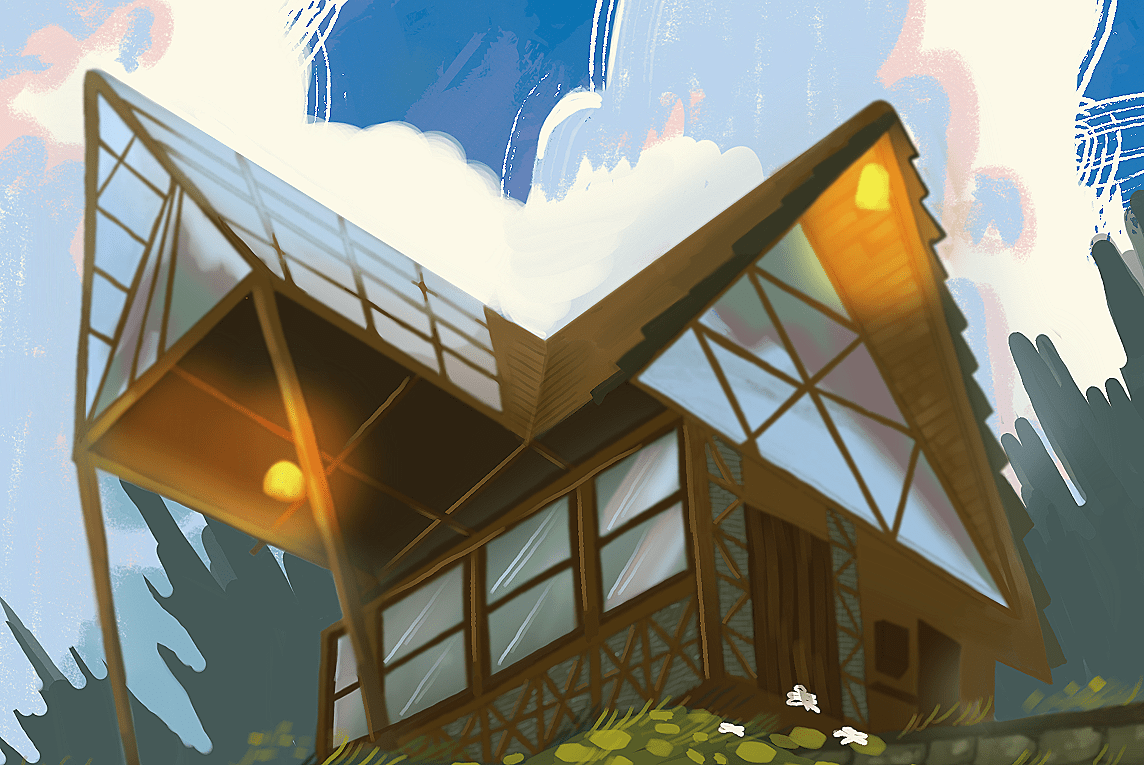

Easily recognisable by its layered interlocking of flat-stacked grey stones and earth-toned planks of deodar wood, kath kuni is widely touted for its earthquake-resistant design. In fact, the building technique came to light when officers from the Geological Survey of India noticed the lack of damage to these structures after the deadly earthquake that shook Kangra in 1905.

In the months to follow, I’d learn that kath kuni is a product of adaptation and genius — one that accounts for the region’s unforgiving weather and delicate ecology while being deeply tied to its cultural practices. I’d also come to the harsh realisation that our goal of existing in harmony with nature seems like a distant one, even in the Himalayas.

On a quest to indulge my curiosity, I made my way to Chehni in Tirthan Valley — possibly the only Himachali village that doesn’t house a single concrete building till date. Once there, I was introduced to the science and ingenuity behind kath kuni. A present-day mistri (mason) told me that the structures’ remarkably low centre of gravity, thick slate roofs and flexible, adjustable walls are the perfect recipe for earthquake resistance. Moreover, raised podiums of stone blocks keep snow and water from seeping into the house, whereas the mud plaster helps to trap heat in the harsh Himalayan winters.

I also visited Chachogi in Kullu district, where I was invited into a century-old kath kuni home by Mohini, a young mother clinging to the hope that her daughter, and several generations to come, will continue living in that very house. Mohini explained that the main door is constructed low, so as to have people bow at the entrance and pay reverence to the household deity, whose carvings adorn the door frames. While open space on the bottom floor allows residents to house their cattle, the upper storeys make for the living quarters since they’re a lot warmer.

Mohini went on to point to a dilapidated building, more like a heap of rotten wood. She told me that the kath kuni structure used to be their house — beautiful, modest and a crucible of memories. However, it collapsed about seven years ago, when the shifting of slates and stones caused water to trickle through the roof. Mohini and her family now use that wood to light fires during the cold months.

It is apparent that the possible demise of kath kuni is underway. Around almost every cluster of kath kuni structures, steel rods now jut out of cement roofs as visible markers of modernity. The few people that can, and do care enough to preserve the craft, are doing so by means of organisations and initiatives such as NORTH, led by local architect Rahul Bhushan. However, increasing prices of wood, corrupt government officials, and the ever-changing shifts in lifestyles and value systems continue to be big threats to the survival of kath kuni. Moreover, the widespread, ill-informed belief that concrete houses are stronger is only worsening things.

Walking around the villages of Himachal Pradesh, I pondered over the uncertain future of indigenous practices like kath kuni. After all, everything — including ingenious ways of dwelling — is bound to adapt to the modernised, evolving world we now live in.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Tarang Mohnot is a freelance writer and journalist. While she travels extensively, she finds it hard not to revisit the Himalayas — over and over again. She is on Instagram at @tarangmohnot.