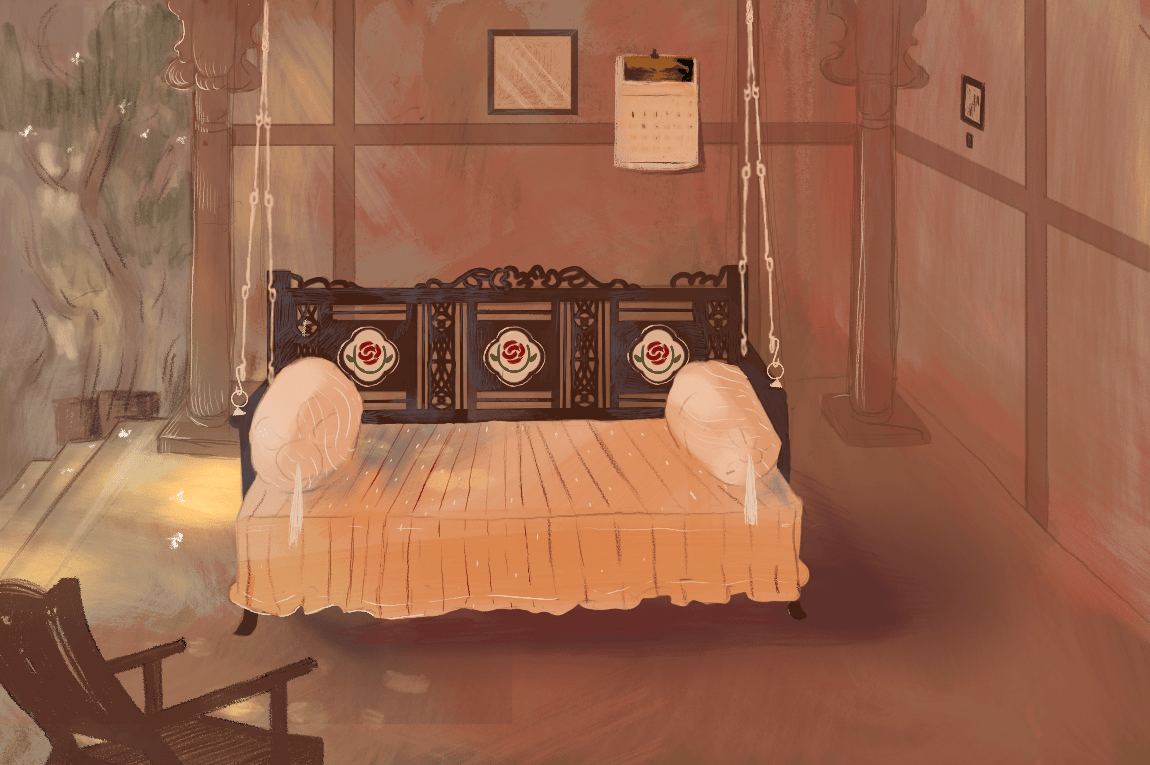

Growing up in Vadodara, my ancestral home was a playground for me. Of all its different components, there was one that stood out most prominently — a hichko or hindolo, a swing with a back rest. Our home had three hichka (the plural of hichko in Gujarati) in different spots, and each one was unique. Of the three, the one in our living room always fascinated me the most — it had animal motifs and intertwining branches of trees. The swing had two large elephant sculptures on either side. As a child, the hichko was my throne and the elephants were my soldiers. All my early memories take me back to the hichko — lying down, having long conversations with my baa, binge-reading the Harry Potter series, or simply curling up and getting lost in my own thoughts. The swinging motion offered a sense of calm and an element of play.

Almost every home I’ve visited in Vadodara has a swing. My interest piqued when I noticed the variations in composition, material construction and design of hichka in different homes. In many homes, architects place kadas, the weight bearings on the ceiling, in multiple places around the house while it’s being constructed, knowing the hichko’s significance and popularity.

To find out more about the hichko, I spoke with Jay Thakkar, one of the co-authors of the book Sahaj: Vernacular Furniture of Gujarat, published by CEPT University Press. He explained that the first representation of the hichko was depicted in Pahadi and Rajasthani paintings of Radha and Krishna. Historically, it was found in royal residences or homes of wealthier families, and meant to depict the hierarchy of power as only the eldest family member would be allowed to sit on it. If a hichko was to be made for a high-ranking person, the ornamentation would be more intricate, with carvings, motifs and embossings. Eventually, this trend trickled down to middle-class and lower-income families, and the hichka became more widely available.

According to Thakkar, a hichko would be placed in a public or a semi-public space. For homes with a courtyard, it would be placed in the parsal — the corridor around the courtyard. Otherwise, like in homes of a sarpanch or mukhya, they would be placed on the otlo (verandah), where neighbours would interact. Initially, the composition consisted of a single wooden plank, commonly known as a paatlo, attached with four weight-bearing ropes to create a swing. Later, to introduce an element of comfort, a back rest was added along with armrests and cushions. This increased the amount of time one would spend on the swing. If a space needed to have multifunctionality, the hichko was designed as a bench that could be detached from the weight bearings and moved to different spaces. In the Saurashtra region of Gujarat, it’s common to find swing beds, which are referred to as dhorni or khaat.

Once the back rests were introduced, they were given a trellis for added ventilation, and during the colonial period, tinted, coloured tiles became a popular addition. Thakkar adds that the legs were frequently shaped into lion paws through the kharadi (wood-turning) process, and within Saurashtra, the bases of the legs would often be enlarged. The chains of the weight bearings were often made with brass-casting work that would depict birds, elephants, diyas or hanging lamps. In more modern constructions, I’ve observed variations in the orientation of the seating arrangements and a more minimalist aesthetic.

Hichka are now commonly found around the country, not just in Gujarat, but they remain an integral, sentimental part of the composition of our homes. It’s been a while since I moved away from home, but whenever I visit, I swing on the hichko, and can hardly tell if it’s the time that’s taken a pause, or my thoughts.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Krupa Patel is an arts administrator and designer based in Toronto, working in urban planning and public art production. She has studied architecture at OCAD University. She is on Instagram at @krupa.gif.

Dharini Verma is a Mumbai-based illustrator and tattoo artist, and is a designer at Paper Planes. She is on Instagram at @dharinigaur.