Established in 1994, Chennai-based Tara Books is an independent publishing house that prides itself in creating handmade, visually striking books that foster a dialogue via storytelling. Co-founder Gita Wolf tells us about the transformation of children’s literature in India, Tara’s focus on propelling indigenous art traditions through book design, and the many ways in which the publishing house cares for its artists.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I’m currently reading Underland: A Deep Time Journey by Robert Macfarlane. If there is a collection of work I return to again and again, it would have to be the essays of John Berger.

Tara Books was established in 1994. How has the concept of children’s literature transformed in India over these years? Do you think the lines between children’s and adult fiction have blurred in this span of time?

Yes, I think children’s literature in India has been transformed. There is far more available — there are picture books, chapter books, fiction and non-fiction but there is also a caveat. Here, we’re primarily talking about books in English. Original work in other Indian languages hasn’t seen that boom yet. That’s a great pity but it’s due to a number of very complex factors which would be too much to go into.

As for the blurring of lines between children’s and adult literature (rather than just fiction) — I’m not too sure. I don’t think so, apart from some select work. Traditionally, before the advent of children’s literature as a genre, the space between what was suitable for adults and for children was liminal. Over a period of time, these categories have actually become more fixed. At Tara, we do have some books that are in the crossover space. In fact, we’re currently working on an illustrated version of a [Leo] Tolstoy story — it is deceptively simple but the ways an adult or a child would read into it would be different.

In one of your earlier interviews you mention how “a combination of aesthetics and politics” has always been fundamental to your work. Could you tell us more about how it manifests into the books Tara makes?

By politics we don’t mean any particular ideology — it is more an acute awareness of how power operates. This can take many forms: it could be through actively bringing in points of view that would not otherwise be heard, or refraining from publishing work that endorses caste, class or gender hierarchies. It means bringing in a context and a location to art and narrative. It also means keeping both human rights and ecological perspectives in mind. Generally, when it comes to such matters — perspectives that are thought to be “weighty” — aesthetics are considered frivolous. We, however, don’t think so. Communication need not always be through a raised fist. Beauty, care, and an attention to how a book unfolds in a reader’s hands to create meaning, is just as important.

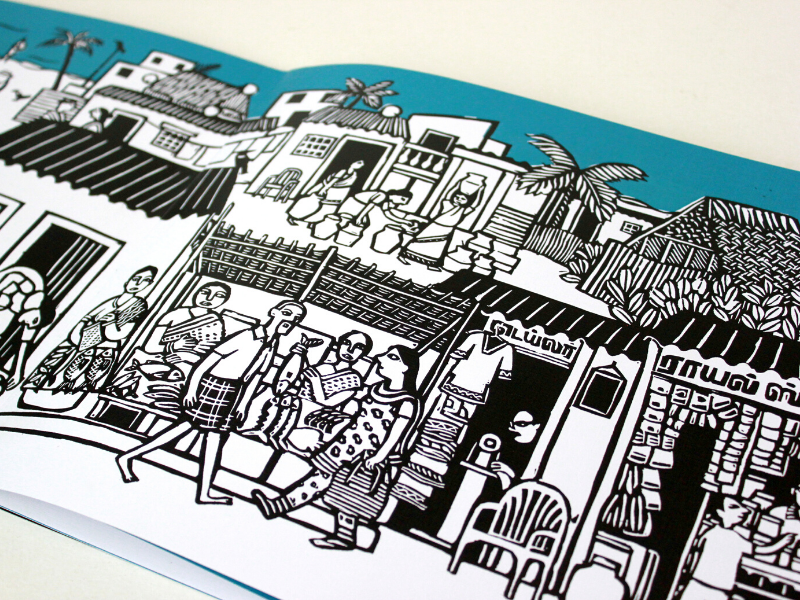

You work with a spectrum of local artisan communities across India ― for both design and craft processes ― providing a platform for talent that otherwise might be untapped or unrecognised. Considering the false prejudice surrounding ‘folk’ and ‘tribal’ art, which oftentimes unjustly relegates the work of the makers of the art, how does Tara work towards addressing the question of indigeneity in art?

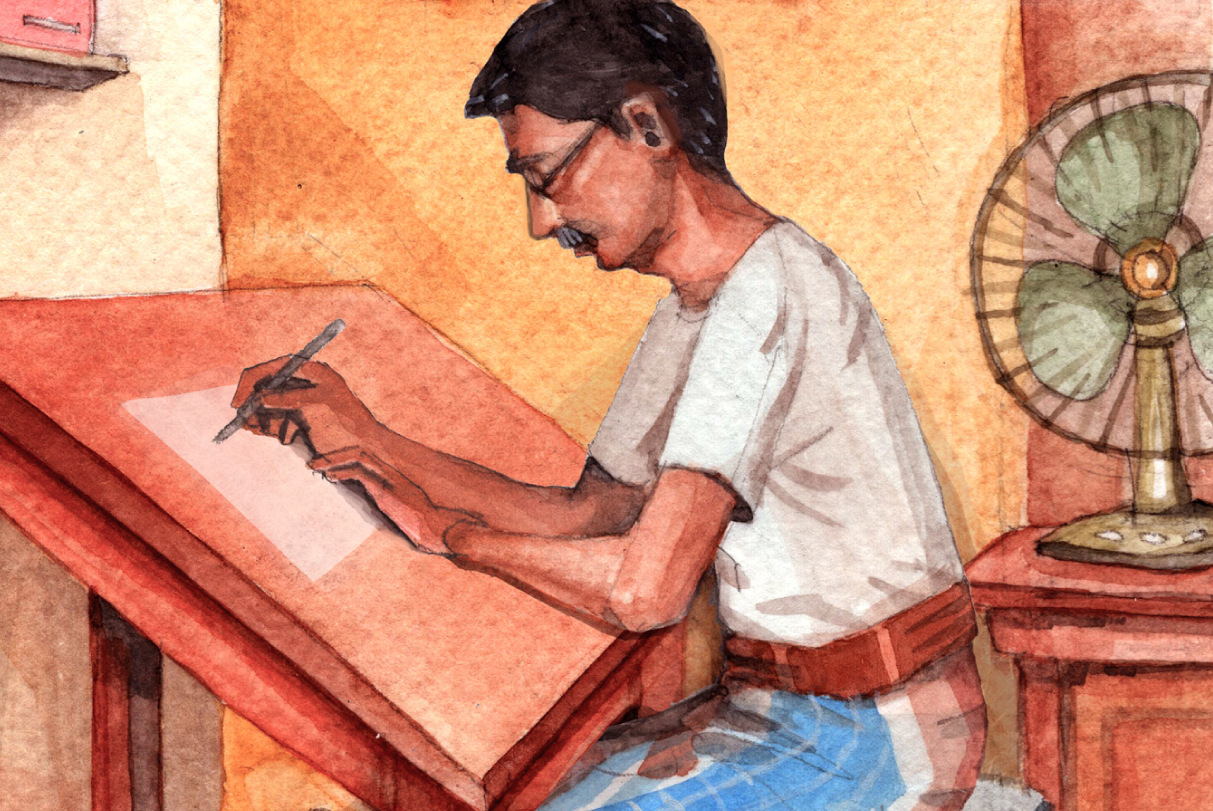

This is addressed, firstly, by working intensively and collaboratively with artists — a process that can take several months. Secondly, by making the artist the protagonist, by supporting them in whatever way they want to tell the story visually and orally — this brings out their worldview and perspective in an intuitive way. And thirdly, by recognising an individual’s work through proper copyright laws and contracts, making sure they receive royalty payments promptly.

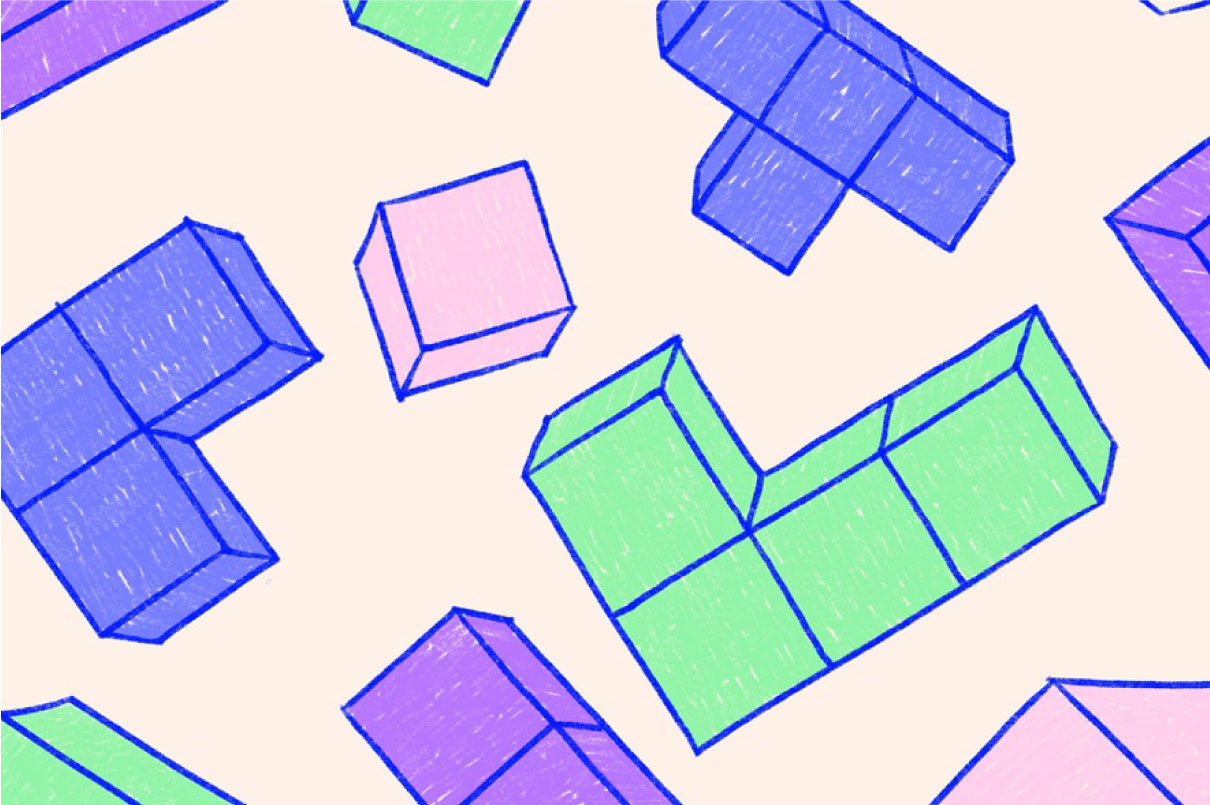

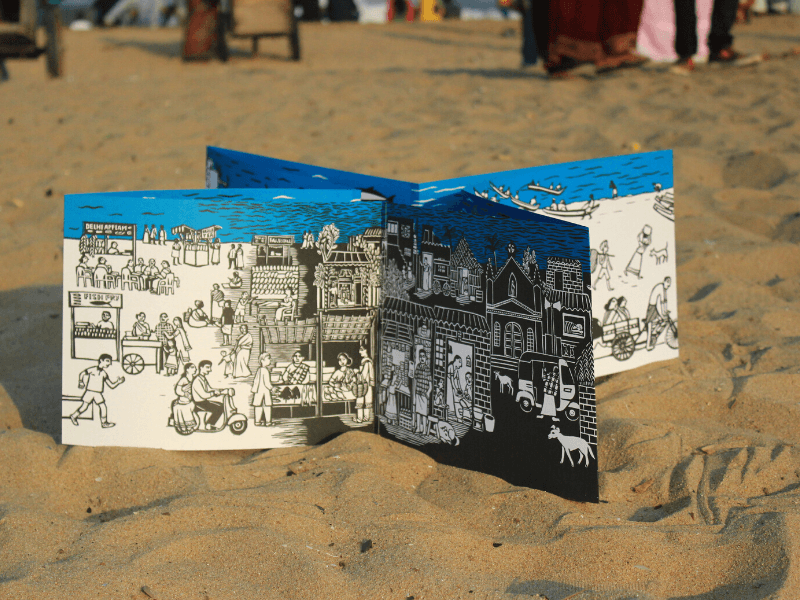

Tara has published titles which involve several experiments with the physical structure or shape of the book, its movement and contours, iterations and amendments with jacket design. Why do you think is it important to play with the form of the book?

While the form of the book as we know it (pages bound together within a cover) is an abidingly good one, we’re excited by what other forms can do to create meaning and experience for the reader. For instance, a particular kind of unfolding can tell a story in stages, interactively. One of our books unfolds into an apartment, telling the story of a little girl looking for her lost teddy bear. Another is circular, following the activities on a local beach from sunrise to sunset, and right in the middle is the sea. The important aspect here is the integrity of the design — the folds, pop-ups and cut-outs are not made randomly; they are part of how particular content can be realised imaginatively and physically. So design is not just an embellishment, it is equally structure and architecture.

Tara has published several handmade, screen-printed books. How do you ensure that the model remains sustainable, both economically and ecologically?

The important thing here is scale — we try to nurture local skills and talent to create employment and a workplace that is run according to fair-trade practices. This needs to be balanced with our vision of creating what can be termed affordable artists’ books. Most artists’ books (printed and bound by hand) are made in smaller numbers, and are hence exorbitantly priced. What we want is to make more numbers, so more book lovers can afford to buy these beautiful books. They’re not very cheap, and yet, particularly when the reader becomes aware of how much labour and care is needed to produce each book, they are not expensive either. It needs to be fair, on both sides. The point is not to make so many copies that our book makers are overworked; to not expand our workshop exponentially so that we lose control, and yet keep it ticking over. It’s a delicate balance.

There is never a single way to translate a book; there might be several styles for translating something. When texts have to be shared with the illustrators, how does this process play out, without creating much tension between the words and the final pictures? How much freedom do you allow for alterations without the original text losing its essence?

Our way of working is very collaborative. We’d like as much freedom as possible, on both sides, without losing the essence of the project. Many of our books actually begin from images — the text comes in later.

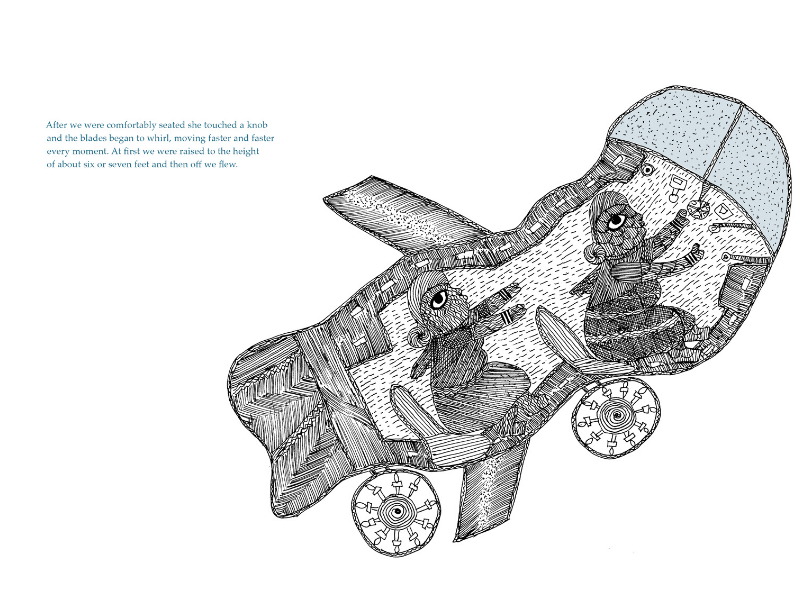

Most of the titles from Tara Books emerge out of a collaborative effort, and embrace narratives that span time, geographies and cultures. For instance, in 2014, you republished Sultana’s Dream ― authored by Begum Rokheya Sakhawat Hossain in 1905, one of the pioneers of feminist thought and writing ― illustrated by Gond artist Durga Bai. How did Durga Bai respond to the century-old text? What was the process of making the book like?

Durga Bai understood what was being said in a deep way. She’s had a history of drawing women doing unusual things — like jumping into waterfalls, playing football, climbing trees and so forth. So when the text was translated for her, she was delighted to try her hand at depicting this feminist utopia. The pictures speak for themselves; Durga has interpreted (translated) the text into images from her own artistic idiom and grammar.

As the one creating the visual identity of the book, how do you keep in mind the aspects of sales and publicity; recall value; of late, shorter attention spans; and given the current times, even a shift towards digital platforms?

We have confidence that what we do — explore and create physical forms of the book — will find their readers. In an increasingly virtual age, there is and always will be a yearning for physicality and a return to the senses. We’d like to keep these qualities alive. Our ideal readers are people like us, and we’re constantly surprised at how warmly our books are received and welcomed. This is an indirect answer to your question: I think we’d like to create a market, rather than respond directly to it. This doesn’t mean though, that we haven’t made mistakes or learnt from them. It is an ongoing process.

Tara Books has recently procured a Classic 1965 Heidelberg Letterpress. Could you tell us what’s in the pipeline?

Yes, it’s the story by Tolstoy that I mentioned earlier, called Little Girls Are Wiser Than Men, illustrated by Hassan Zahreddin, a Palestinian lithographer. We’re making blocks and printing it on our letterpress. It’s exciting.

Does your job leave you with ample space to read for leisure?

My other job currently is that of an organic farmer — something I’ve always wanted to do. My reading now is largely about natural history, gardening and other botanical subjects. I wouldn’t say I have ample space, but definitely enough to keep reading. And I’ve discovered a wealth of podcasts to listen to!

Shop for a selection of Tara Books here.