In 2017, my friend and I visited Kochi for our first ever annual ‘sisterhood’ vacation — a trip we now semi-religiously adhere to. Today, Kochi is my home. It houses the locality of Mattancherry — an architectural and cultural convergence of Keralan, Dutch, Portuguese and Jewish influences — at the heart of which lies Jew Town.

Of many theories of how a Jewish community came to be in Kerala, one is that Jews travelled to Kerala through the trade relations between the Malabar coast and the Middle East under King Solomon’s reign (970–931 BCE). It is said that between the end of the 15th century and the 16th century CE, persecuted Sephardic Jews — also known as Paradesi Jews in local parlance (or ‘White Jews’) — fled the Iberian Peninsula and arrived in Kochi (then Cochin), and were granted refuge and land by the Raja of Kochi, Rama Varma. They formed a prosperous trading populace and built the community-centric Jew Town. The Malabari Jews (or ‘Black Jews’), mostly involved in trade and craft, are believed to have arrived in Kochi before the Paradesi Jews, and commonly settled outside Jew Town.

Today, Jew Town is lined with colourful two-storeyed yesteryear homes, now converted to boutiques and cafes. At the end of Synagogue Lane, my eyes land on the Paradesi Synagogue. Originally set up by Samuel Castiel, David Belila, and Joseph Levi in 1568 CE, the synagogue was destroyed by the Portuguese in 1662 CE, but was restored by the Dutch when they took Kochi around two years later.

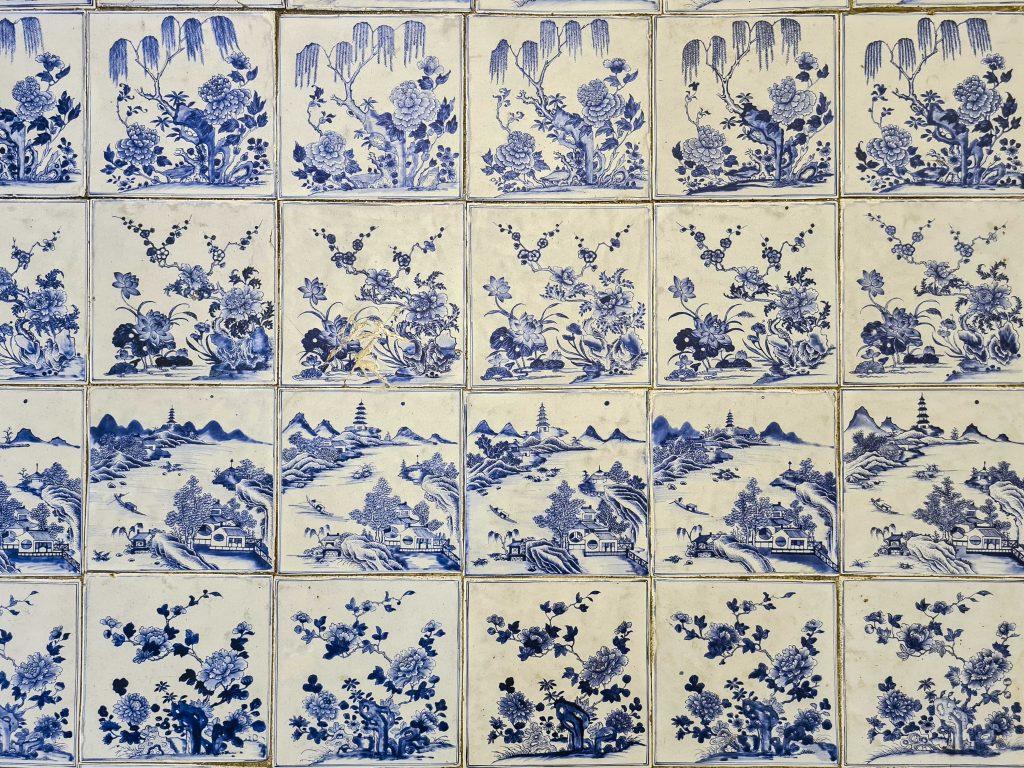

As I walk into the Paradesi Synagogue, the windowed hall grants me respite from the heat. That’s when I see it — a revelation of brilliant blue and white-turned-ivory tiles under my feet, almost imitating ink blots on a blank sheet of paper. The floor is paved with 1,100 hand-painted, willow-patterned Chinese porcelain tiles, which were imported from the city of Canton (a previously used name for Guangzhou) in 1763 by the Jewish businessman Ezekiel Rahabi.

Calligrapher and historian Thoufeek Zakriya, who explores the cultural heritage of the Jewish community of the Malabar region, tells me that each tiled row follows one of four sets of patterns, with a unique belief of what they mean. Two patterns — a lotus and a prunus which symbolise summer and winter, and a chrysanthemum with a willow which depicts autumn and spring — are believed to portray contrast as that of between a husband and wife. The pattern with a tree peony and a boulder is believed to signify good fortune and eternity. The rural scenery pattern that features willows, is popularly believed to be a reference to either one of two legends. The first narrates the tragic love story of Knoon-se, the daughter of a powerful Mandarin, and Chang, a secretary to her father, who were separated by death, and immortalised as turtledoves. The other describes a Shaolin monastery burned by troops of Manchu rulers — the monks’ souls, now doves, journeyed to the City of Willows, said to be the Buddhist heaven.

While it is clear that the tiles were brought from China to Kochi for this synagogue, there are several stories of how exactly they ended up here. Johann Binny Kuruvilla, founder of The Kochi Heritage Project shares an interesting legend that contests the synagogue as the intended destination of the tiles — initially destined for the Raja’s palace, the tiles were redirected to the synagogue when a clever Jew convinced the Hindu royal that they contained cow’s blood, making it unfit for his palace.

The visual impact of these tiles — which also reminds me of British engraver Thomas Minton’s willow patterns on English creamware — is noteworthy. The colours blue and ivory contrast nearly everything else, including the central pulpit with brass rails, the carved teak ark which houses the Torah scrolls, the jewel-toned glass lanterns, and the 19th-century chandeliers imported from Belgium.

In the bustling heart of old Kochi, amidst the cacophony of daily life, the Paradesi Synagogue stands as a silent storyteller. Its tiles whisper volumes of the bridge between geographies and cultures, of community, and of the rich history that the city has witnessed.

Find your way to the Paradesi Synagogue in Kochi via Google Maps here.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Niviya Vas is an independent content writer based in Bangalore. When her rescue cats allow, she slow-travels and documents her experiences in her blog, Commoner’s Causeway. She is on Instagram at @niviyavas.