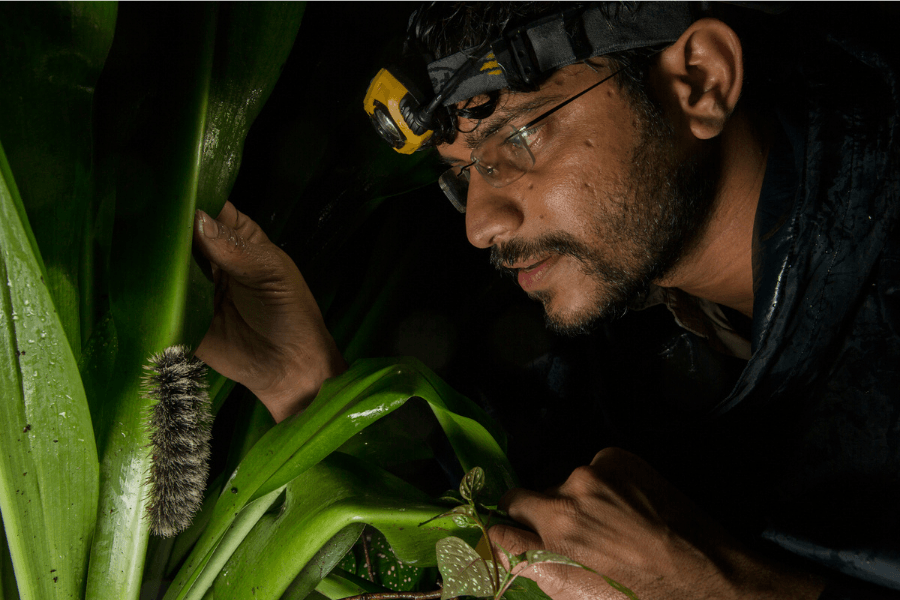

Prasenjeet Yadav found himself in Himachal Pradesh as India went into a stringent lockdown in March this year, amidst the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, but managed to get back home to Ghorpad near Nagpur, where he has been spending some well-earned time. Collaborating with researchers, policymakers, scientists, and conservationists, Yadav’s projects highlight sensitive issues surrounding climate change. He is also a founder-member of Shoot for Science, an initiative to train science communicators.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I am currently reading The Hungry Tide by Amitav Ghosh — a beautiful work of storytelling and a brilliant piece of writing. As I’m unable to read just one book at a time, I’m also in the middle of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari, and The Song of the Dodo by David Quammen.

A book I keep revisiting is Jim Corbett’s Man-Eaters of Kumaon. Its stories take me back to a childhood spent in Ghorpad near Nagpur — steeped in the lap of nature and the wild.

One of your early assignments took you to the Sikkim Himalayas. Could you elaborate upon what it entailed and how it sparked your interest in telling stories using photography as a medium? Moreover, how have your growing-up years influenced your ability to tell stories?

I grew up in the village of Ghorpad in central India, some 35 kilometres away from Nagpur. I have literally been living in a jungle where tigers and other wild animals roam around. I learnt storytelling in the most traditional manner — sitting around a bonfire with family members. Growing up, I was labelled as a rather curious child as I used to ask a lot of questions. While I was trained as a molecular biologist working in laboratory, at heart I was someone who would enjoy working outdoors. So the next step was to figure out a way to combine my interest in wildlife with molecular biology.

I moved to Bengaluru in 2010 to complete my Master’s dissertation at the National Centre for Biological Sciences. Post-dissertation, I joined NCBS as research fellow and worked in a laboratory for four years, publishing papers on the genetics of tigers and leopards. Whilst working, I realised there exists a communication gap between the scientific and non-scientific communities in the country. This is when it struck me that I could use my experience in research along with my storytelling skills to attempt to bridge the gap. I took a sabbatical from my ‘academic’ career and that is when the assignment in Sikkim came about. I always had a keen interest in photography but had no training. Moreover, I procured my first camera only while I was in Bengaluru.

In 2012, I collaborated on a funded project called ‘Sikkim Chronicles’ with a scientist. Along with the paper, we presented it in the format of a photo-story. We documented the abundant natural beauty of Sikkim and the effects of climate change on its fragile ecosystem. The concept of ‘science storytelling’ barely existed in India then. When the researchers showed the photo-story to the funding agency, they extended the funding further.

You spent the last three years capturing the snow leopard in the village of Kibber in the Spiti Valley ― being on your own in a remote location, almost isolated, in frigidly cold conditions. With the challenges posed by the environment, how do you prepare for that moment when you think you will spot a leopard? Has the experience enabled you to perhaps rekindle a connection with the wilderness and sentient life forms?

There was a gap of about five years between the time I began work on ‘Sikkim Chronicles’ and the snow leopard project. Back then I was unsure how to make a living out of what I was doing; there were hardly any natural-history storytellers. Someone asked me to apply for the National Geographic Young Explorer Grant, and I became the first Indian photographer to receive it under expedition/storytelling council. It was supposed to be a three-month-long project but I spent almost two-and-a-half years working on it. When I presented the work at the NatGeo headquarters in Washington DC, they were glad to see images from India that weren’t depicting the Taj Mahal, temples or tigers. They then took me under their umbrella and I worked on multiple stories for them, from one about the birds in the Himalayas to the carnivorous bats in Mexico, to travelling to Mongolia and Kazakhstan to work on a photo-story on mountain goats.

To photograph the snow leopard in the village of Kibber in Himachal Pradesh, I had to move to the mountains, almost 5400 metres above sea level. There was no preparation for it as such; the preparation happened when I began working on the project. Moreover, I learnt a great deal as I was surrounded by people who had far more experience than I did. In Kibber, the locals were my family — they would point me to the right locations and I would cook food with them and take care of their children. I lived and learnt with them.

Speaking of rekindling a connection with the wilderness, I have always been mindful of dipping in and out of the places and circumstances I find myself in. Even now, I think I can easily disconnect from social media or my phone. While in the Himalayas, I learnt so much about myself — about how the human body adapts to extreme conditions, how human bonds are formed. For instance, I was completely alien to the local people, yet there were no barriers whatsoever because of a sense of vulnerability and even trust. Say if I fell and broke my arm, no helicopter would zoom in to rescue me and fly me to a hospital in Delhi. The locals knew I was as dependent upon them as they were dependent on each other, and I felt way more secure than I ever have in any city.

In earlier interviews, you’ve made mention of the remote camera trap set-up you designed. Could you tell us more about it and how you went about developing it?

Well, let me begin by saying that I am definitely not the first person to have used the remote camera trap set-up. The American photojournalist Michael ‘Nick’ Nichols — who is known for his phenomenal body of work — developed it in the 1990s.

A remote camera trap set-up is used to get really intimate shots of the animal in its natural habitat. Such a set-up was never used in extreme conditions of minus 40ºC at 5000 metres. We designed the trap in a way that it could withstand the temperature and run for weeks together. I set up something resembling a selfie booth in the mountains — there was a camera body with a lens and anywhere between 3-5 external camera flashes. Each camera flash varies in intensity, with a different role to play from the others. The other unit comprises a remote trigger, like an infrared beam. When the beam is obstructed [in this case, by the snow leopard], the camera receives a signal to capture a photograph. Each time it had to be set up, it took me 3-7 hours. Designing the contraption took several months, and I sought help from several of my friends who were trained as engineers. The wires were custom-made by a friend in Gujarat. Of course, the team from NatGeo also lent their expertise and understanding. We could have simply hired someone to make this but I knew that once I was in the mountains on my own, I had to know the inner workings, in case something went wrong. One has to learn these skills.

When do you know that a particular series you’re working on is finished?

I don’t think I have ever known this feeling because the day you think you have, you’re done. While working on the assignments with NatGeo, one is collaborating with photo editors and writers on very constrained timelines. I might have gotten a photograph after waiting for the right moment for ten days, or I might have taken just ten minutes to capture something while driving past. The bias towards the effort I have taken to make that photograph is mine alone. The photo editor may not look at it that way, and might prefer an image which barely involved any effort over one that did, without even knowing it. Most editors will tell me that the story is over once the deadline is met.

What does a photograph need to do, or have, to hold your attention?

A powerful photograph is the one that can change the course of history and we have seen this happening through still images time and again. A powerful photograph needs to have a character, a life of its own, and a sense of focus/purpose. If you were to look at the photo again and again, you would do so from a different perspective each time. A natural history photographer may not be able to accommodate all these attributes but if one spends enough time, it’s possible. Photographs aren’t just about movement and action; one has to keep the larger storytelling angle in mind. I don’t consider myself a traditional wildlife photographer but a visual storyteller focusing on natural history who thinks in sets or a series of images in order to tell stories.

You began your career as a molecular biologist and later worked as a research scientist studying the movements of leopards and tigers, before photography became your calling. With a vocation that brings together science and natural history from a visual and sensorial point of view along with the pressing concerns surrounding the ecological and conservation sciences, how do you create an arc of storytelling that sensitizes without being excessively preachy or didactic?

I think it is important to live every story before you narrate it. You have to give it time, experience it, and get a personal, first-hand narrative. It is not just about having technical prowess; I know I am patient and that I can immerse myself into a story I’m working on. When you spend 20 days in a new place and consider yourself an expert, it stems from a sense of having a lack of a complete picture. So when you begin to tell your story, it undoubtedly comes across as preachy or supercilious. On the other hand, when you spend a comparatively longer time, you realise you know so little about the place. However, it then comes with a sense of personal experience and time and what was going on in one’s mind — it then becomes thought-provoking, not preachy.

I also think reading plays an extremely vital role. Besides, my experience in research work has taught me that you will never be in a position where you think you know everything. Meeting people and collaborating with them is equally essential. A fruitful collaboration is when two people watch each other’s back and learn from each other. The language of science is objective, and it has to be so. About 80 per cent of the work scientists do would be termed as ‘boring’ but then when you bring these so-called ‘boring’ and ‘interesting’ parts together to create something, it takes time. Additionally, there is no single formula — the permutations and combinations that work for me may not work for others.

Has the pandemic changed the way you work, considering the several unpredictable impairments as far as travel is concerned?

My plans made in the ‘previous world’ would have certainly taken me to various places. Instead I am back home in Ghorpad, in the central Indian landscape, in the place where I grew up. The time taken off during the pandemic has, in fact, made me step back to look at the last six years of working constantly in the field to carve a path for my stories. It has made me look in retrospect and evaluate many choices, along with bringing a much-needed sense of calm to just be in one place. However, I now feel motivated and hopeful, and the time spent at home has also enabled me to work on proposals for future projects.

What advice would you have for those who want to pursue telling stories about the wild or want to contribute to the larger ecological community but are unsure about where to begin?

Begin at home! There is a misguided notion that you have to quit everything to be a storyteller or a conservationist. Giving back to the ecological community is not a profession but a choice. Anyone can explore the ‘wild’ around their house — for instance, something as simple as observing ants eating crumbs of biscuits or the flight patterns of birds you see at your balcony. For those wanting to publish (if you aren’t making a living out of it), there are multiple online platforms on the lookout for interesting stories, or one can even create their own blog. Do not stop what you’re doing to do this but make it a part of what you’re already engaged in. You can be a lawyer and guide scientists and activists with environmental laws; you can be a restaurateur and be mindful of wastage, the provenance of your ingredients, and questions of sustainability. Sensitivity towards the ecology is a lifestyle, irrespective of who you are and what you do. It isn’t idealistic but very real — the air you breathe, the food you eat, the water you drink.

What are you working on next?

Currently, I am at the post-production stage of some of my earlier projects, the field work for which was carried out before the pandemic struck. I am also in the process of pitching a new story I want to work on next year. Moreover, I am exploring my backyard and documenting my childhood memories. But I am largely photographing my nephew who has just started walking and seems to be as curious as I am!

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)