Straddling the space between documentary and art, London-based photographer Kalpesh Lathigra’s work has been featured in a number of international dailies and magazines. The recipient of the World Press Award (2000) tells us why he no longer is a ‘photojournalist’, what it takes to make the right portrait, and the importance of trusting his intuition.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I am currently reading Known and Strange Things by Teju Cole and Bombay, Meri Jaan: Writings on Mumbai [edited by Naresh Fernandes and Jerry Pinto]. The book I frequently revisit is Interpreter of the Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri — there is something about those stories that resonates every time I read them.

You worked as a photojournalist with a newspaper in the UK for almost six years. Could you tell us about your first few assignments and what keeps you drawn to the medium after all these years?

My first full-on experience working for a daily newspaper involved photographing the Political Conference season in the UK in 1994. It was the best and worst of experiences — a baptism of fire with regard to the competitive nature of the industry. Being part of a team taught me about the importance of self-integrity. I also travelled to Bangladesh to make a series on arsenic poisoning through groundwater wells and returned to the country during severe floods. I’ve worked on a range of projects — from a series on HIV and famine in Malawi to photographing daily news events in the UK — and I have to add that I am no longer a photojournalist. I still have the tools, metaphorically speaking, but I really have nothing to say as a journalist. I am an artist.

What keeps me drawn to the medium is difficult to answer in any real tangible way; I am not very good at expressing myself. I can say I’m interested in what a photograph can and cannot convey: its relationship to the viewer, the artist, and what the subject is — whether it’s a person, a building, a landscape or an object — and how these move me emotionally, thus allowing an intuitive approach.

You received the World Press Photo Award in the Arts & Entertainment category in 2000 for your photograph of Kathakali dancers at Globe Theatre, captured just before they get onto the stage. The composition of the photo is exceptionally choreographic, even before the performance has begun. Can you tell us how you went about creating it?

There really is no formula except that I spent time with the French choreographer Annette Leday and her company for a while, maybe a week, until they forgot about my presence. During this time I watched the moments unfurl in front of me. I was simultaneously testing the use of a portable flash and the possibility of Impressionism which then allowed the photograph to have that particular feel. In many ways it is replaying the idea of staging in photographic practice — I was on auto-pilot because that specific scene had played out over and over in my mind.

What has been the one photo story you worked on which enabled you to cut your teeth in the craft of being a photographer? Why?

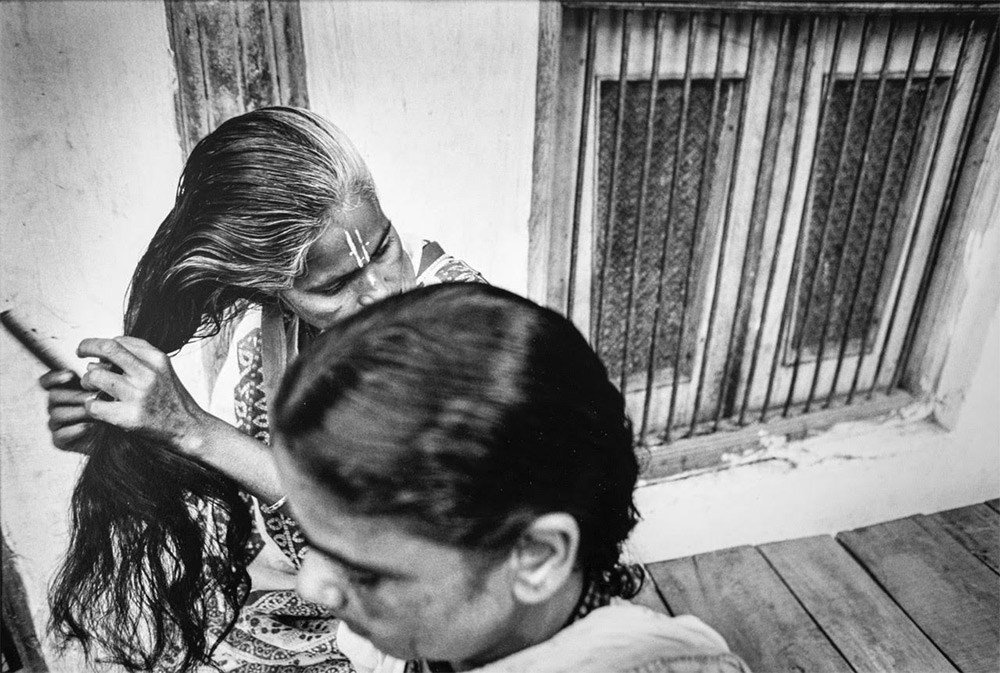

The Brides of Krishna. This project was photographed in Vrindavan in Uttar Pradesh from 2004-2007, looking at the lives of the widows who live there. It’s interesting you say “cut your teeth in the craft of being a photographer” — this story let me experiment with the narratives of story-telling using different camera formats including 35mm, Medium and Large formats, all made on black and white film. So when we talk about the “craft” I’m thinking of the technical aspect, right from the use of these cameras to the final prints in the darkroom. But if we are talking about the effect of the intangible on my photography then it’s a different conversation. This story allowed me to give myself permission to move away from journalism and onto the path of art, evolving my practice and posing questions I am still asking myself when it comes to photography and its role in society.

When do you know that a particular series you’re working on is finished?

It’s when I have nothing more to say. In some ways the practical answer is that I stop seeing and being challenged.

Is there a learning you find yourself returning to with every subsequent shoot?

I’ve learnt that the organisation of logistics is paramount as it frees me to actually make the work. This includes things like travel arrangements, having assistants, lighting, contingencies and so on — once these are in place I can forget about them. Of course, on a personal level, being open to serendipity always helps me.

Portraiture is a significant constituent of your practice. What are the main challenges of getting the right portrait, or a selection of portraits, every time?

The main challenge has always been that of time, especially with commissioned work. I try to keep my set-up simple; it allows minimum waste of time to get the right portrait. Then it’s really down to trusting my intuition of the situation, the location. My brain computes really very fast and that’s owing to my past experience as a photojournalist.

How important is it for you to work across disciplines, say with a writer or an actor or even another photographer? Do you think collaborations help garner a greater pool of ideas?

I wouldn’t work with another photographer. I have, in the past, and it was a wonderful collaboration but I work best alone. Having said that, certainly in the field of fashion, I enjoy working with stylists and fashion directors since they bring a different sensibility to the project and an essential attention to detail. Writers are great [to work with] but not when they tell you what photograph to take, so the best ones are those who leave you to it and how you interpret the writing.

I am currently working on a collaborative project Memoire temporelle, comme un Mirage [A temporary memory like a mirage] with Emmanuelle Peri, who is a Photography Director in London with a background in Art History and Museology. This collaboration is not about garnering a pool of ideas. It is a dialogue of the narratives in the work, the nuances of its visual language, the emotional resonances. How the work is read by someone you trust implicitly — in that aspect of the collaboration it is about giving the work away to Emmanuelle without interference from me.

With the proliferation of newer visual platforms on social media, has the vocabulary of showcasing a certain kind of ‘beauty’ undergone a transformation? Do you think the portrayal of subjects in this realm is gradually becoming more honest?

All I can say is that these platforms allow expression and dialogue which existed earlier but wasn’t shown in mainstream magazines. Simply put, people of colour, of different body sizes and so forth weren’t included in the mainstream. [Newer] platforms have now garnered strength to have these conversations that lead to change.

How do you strike a balance between personal projects and editorial commissions? Do the two feed off each other?

In some ways, yes — sometimes a proliferation of an idea can emerge from a commission. Take, for example, the passport series where I’m commissioned to make a portrait of an actor. I make a technically sound, evocative photograph that ticks all the right boxes but as an artist I am more interested in the idea of a democratic portrait, so using a passport camera [a Polaroid Studio Express Model 403 Passport Portrait Instant camera] with instant film. Editorial or commercial commissions provide financial support to live. The balance, if there is one, for me is disappearing to make personal work; I can’t just be a jobbing photographer. There’s nothing wrong with that and I have respect for those who do so and make great photographs but it’s not me.

Who would be the one person you’d like to have shot your portrait?

Can I actually mention two? They’re both [my] friends — Stefan Ruiz and Nigel Shafran.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)