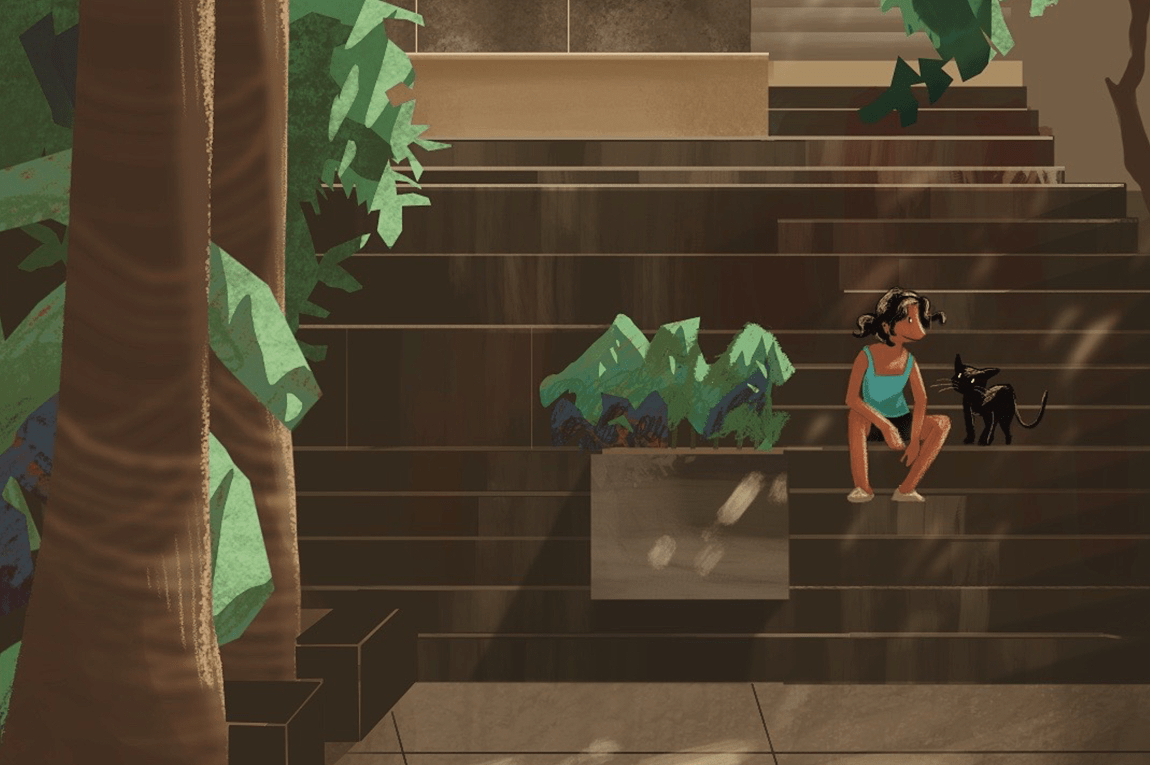

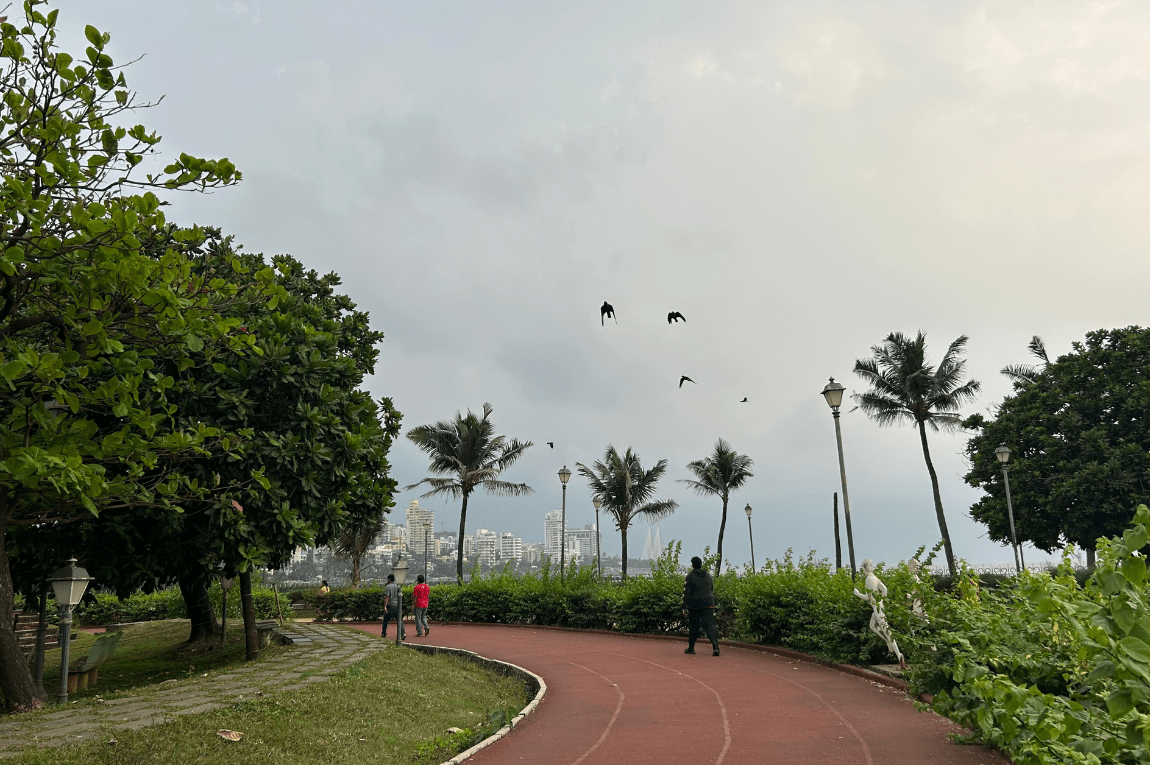

When I moved to Mumbai in 2017, I came to realise just how infamously busy the area of Dadar is. I dared to venture into the neighbourhood, and learnt that it houses the popular Shivaji Park, which has a rich history as the city’s cultural nucleus, and has seen the presence of several influential figures in arts, literature and politics, like writer and poet PK Atre. The park is dear to cricketers across the city, and to some greats including Sandeep Patil and Ajit Wadekar.

The last time I visited the area was late last year, when I was walking around with a friend, and spotted a charming blue-banded, symmetrical bungalow. In addition to its curvaceous eyebrows (window shades or chhajjas) and the pillars of the balconies, the lettering style of the building’s name, Vandan, reminded me of a typical Art Deco building one would spot along the Marine Drive stretch. As we walked further, I realised Vandan was just one of the many buildings of this style in the area.

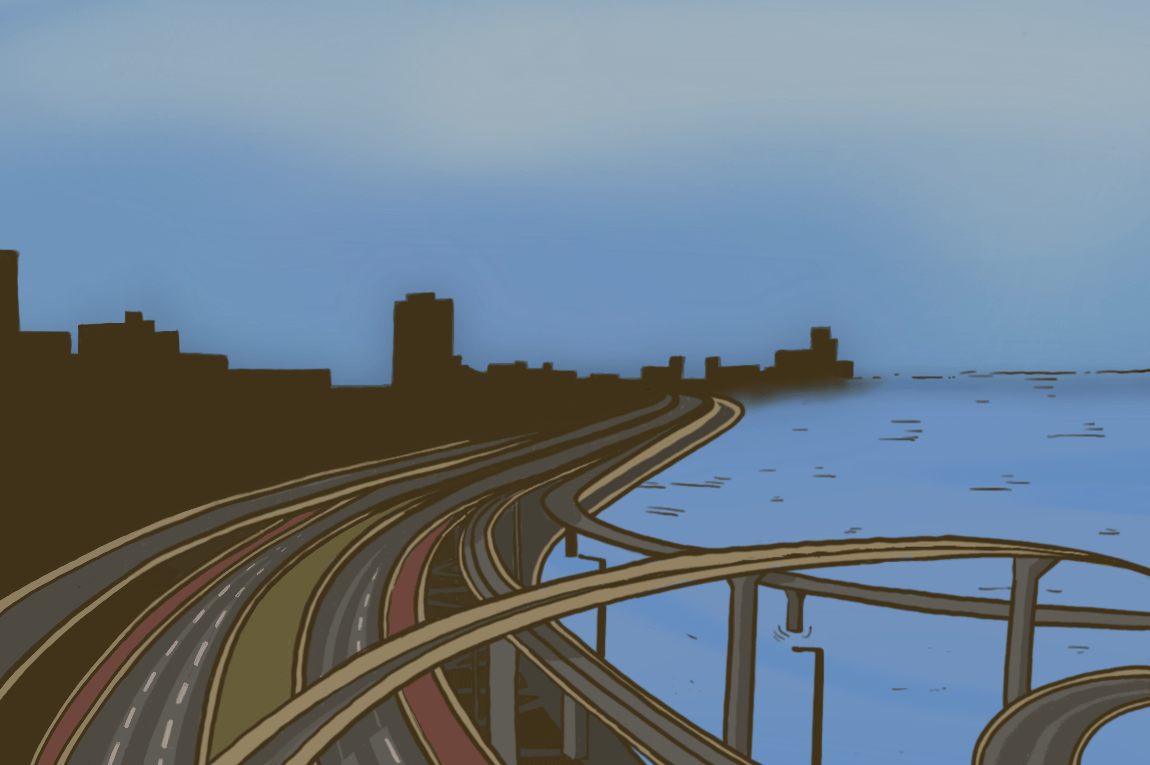

I later found that these buildings came up in the aftermath of the bubonic plague of 1896, when Shivaji Park was conceived to decongest the city’s dense areas. The British government, attributing the plague to poor hygiene in crowded areas, formed the Bombay City Improvement Trust (BCIT) to ease congestion and promote sea breeze in landlocked zones — an initiative that popularised the apartment typology seen here today. The BCIT also laid out guidelines for building height and streetscape to ensure that the structures received sufficient sunlight and ventilation.

Unveiled to the public in 1925, Shivaji Park underwent subsequent development. The surrounding land was gradually sold to interested buyers during the 1930s — a period during which Art Deco was gaining speed in Mumbai, and moving northward through the city. The structures around the park — three-storeyed buildings in four curved rows — were mostly designed by Indian architects. Apartments here, due to their lower building costs, proved to be attractive for middle-class residents. The building material of choice was reinforced cement concrete (RCC), due to its affordability and robustness. The choice was supported by Bombay Municipal Corporation’s Chief Engineer, NV Modak. Author Nikhil Rao, in his book, House, But No Garden: Apartment Living in Bombay’s Suburbs, 1898-1964 (2013), highlights the trend of the middle classes shifting to this locality, and points out another reason for this: “The vast majority of such builders were middle- and upper-middle-class residents of older parts of the city, who would often themselves take a unit on the top floor — or indeed, even the whole top floor — while renting out the other units to ‘people of their own status’.”

“I also spot buildings’ names in Art Deco lettering in the Devanagari script. The building Hari Nivas on Raja Badhe Chowk features the popular Art Deco motif of a frozen fountain, which symbolises eternal life. The corner building also has a turret or a viewing gallery on the top floor, providing what could possibly be the finest view of the area.”

While I walked around, I noticed that the buildings here have more subdued Art Deco features than the ones in Churchgate and along Marine Drive. Once, during a guided tour with Art Deco Mumbai around Matunga, a locality neighbouring Dadar, I was informed that the residents prioritised modesty and avoided extravagant additions to structures. They also infused their religious identities in the structures — evident in symbols on window grilles and gates — adapting Art Deco as their own.

Several common features of the style are noticeable here, like the raised eyebrows on corner windows, compound walls with concrete grilles, patterned window grilles, and spiral brackets. I also spot buildings’ names in Art Deco lettering in the Devanagari script. The building Hari Nivas on Raja Badhe Chowk features the popular Art Deco motif of a frozen fountain, which symbolises eternal life. The corner building also has a turret or viewing gallery on the top floor, providing what could possibly be the finest view of the area.

The locality has been undergoing rapid change. As I reached the end of my walk around the neighbourhood, I saw many structures covered with scaffolding. In 2016, giving in to strong opposition by the residents on designating the area as a ‘heritage precinct,’ the government limited heritage status to the park, allowing development in the surrounding area.

As I left Shivaji Park, I couldn’t help but think of the communities formed here over decades. Regardless of what its future may hold, the neighbourhood will undoubtedly remain an iconic part of Mumbai.

Our selection of stays across India, best visited for their design and style. Check in

Pranay Dewani is an independent writer and researcher who loves exploring art, culture, and film through their writing. They are on Instagram at @shutupbyrd__.