Founder and Artistic Director of Thresh, a performing arts collaborative, New York-based Preeti Vasudevan aims to create experimental productions that encourage provocative dialogue with identity and erase boundaries through performance. The award-winning choreographer and performer tells us about her relationship with the stage, the importance of disengaging from one’s work, and why Tamil is her body language.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I’m currently reading Zadie Smith’s White Teeth. I do visit Ka by Roberto Calasso frequently.

Being on stage is a coming together of bodily movements, sonic or rhythmic influences, an awareness of being watched, and a certain state of consciousness, of being ‘in the moment’. How do you negotiate vulnerability here, more so if the performance draws from intimate or personal experiences or alludes to autobiographical references?

The stage, to me, is the only place I allow myself to be fully vulnerable. It represents, to me, the notion of a womb where you stand naked, where there is nothing to hide and only you to behold. It’s not easy but the more honest you are with yourself, trying not to be someone else or please others, then this space becomes a truly energised one. Autobiographical storytelling allows one to be vulnerable but they also have to be edited strongly so that they don’t become needy and overindulgent. A sensitive ‘outside eye’ can help in this process as it is a performance in front of an audience, and not a therapy session. Once personal stories are told, they have the effect of having given birth — it is yours but it also has its own trajectory and journey. The more we allow that story to breathe freely the more honest and vulnerable one can be, reflecting on the impact of telling that story.

In the process of working on a new performance, what usually dictates or propels the approach you take on?

Apart from movement, what I bring into the studio emotionally or psychologically [on] that particular day dictates the approach. Once I get a few ideas going, I start to see a pattern or a map from where I can begin to draw a framework.

In the case of your own previous work, do you feel the need to revisit it, finetune it, adapt or use it perhaps as a catapult to create new work? Does it then assume new meaning and significance?

I try not to edit too much as that [piece of work] was a specific journey. There may be minor tweaks and some tightening but the more frequently I perform a piece, the tighter it gets and then eventually settles. New work is almost always influenced by older work as there is a certain stream of consciousness. It depends where and when it comes to create a new thought.

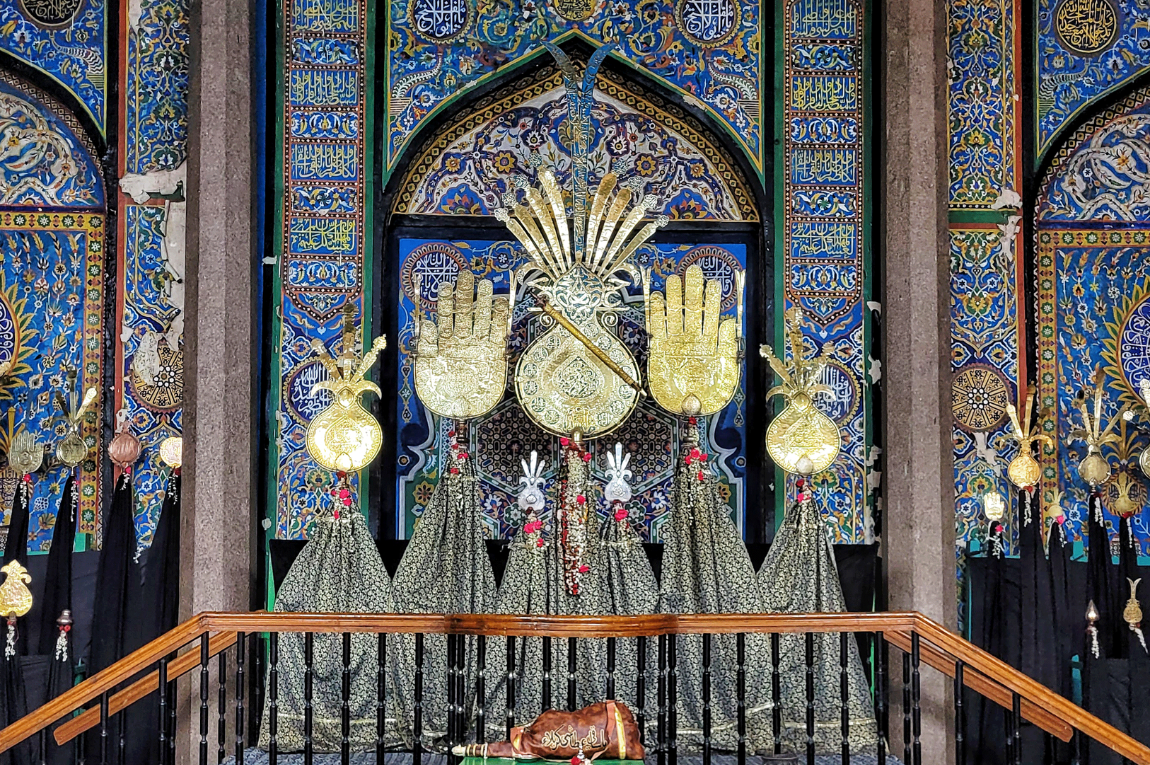

Your solo performance ‘Stories by Hand’ (2017), co-created with writer and multimedia designer Paul Kaiser, tells a story primarily through gestural languages — mudras and dance movements. In your narration, you mention that Tamil is your ‘body language’. Could you elaborate on this? What languages were you working in whilst conceptualising the performance, given that you are multi-lingual?

Yes, Tamil is my body language as that is what I grew up hearing at home. All things home-based were in Tamil — instructions to the cook in the kitchen, grandmother talking about all and sundry things, parents chatting with the vegetable vendor, the cook, a neighbour, or hearing the prayers mumbled in the puja room or discussing something with an older family member. These are visceral and sensorial and your brain thinks through the body to communicate with a language used in this manner. English being the formal language took over a more intellectual area and thus remained in my head! Formality took over and the body language for it was more restrained. I worked in English with Paul, but then I explained my gestures by speaking of their Sanskrit terms, meanings and symbolism, including what Tamil does. So I would say Sanskrit, Tamil and English.

What are your thoughts on making the work of an artist or a performer open and available to other people to learn from?

I am not entirely sure about this question — is it about another artist whose life story I create and perform? In which case, I am totally open to it and would have to do some deep research to understand their public and private life and then have an internal dialogue with the person to make it mine and make it authentic.

Is disengagement from your own work important?

Yes. Over-personalising it means entering a danger zone. One can become overly defensive and sensitive when others disagree or simply don’t like what you do — that’s subjective but if you don’t disengage enough, the work and the artistry suffers. But disengagement doesn’t mean you lose connectivity and vulnerability — it means to let go, be allowed to breathe, watch it with fresh eyes, and relearn.

Is there a kind of stage that you find most nourishing, and then something that you find most difficult in your creative practice? How do you deal with roadblocks while working on a performance?

I love old spaces as they carry years of collective artistic energy. It’s like magic — when you walk into the space it feels as if you’re talking to various spirits from different times. It is alive and charged. A brand new space is challenging as it’s a very sterile environment and is almost too perfect. You need the flaws, the rawness, the broken bits.

Roadblocks will always be there. Breathing is a great technique as is putting on some music and moving around without any agenda. Every day is different and accepting that sometimes does take the pressure off.

What sort of influence do informal conversations with co-writers or other performers or those from your troupe have on your work?

They help in the reflection of oneself and one’s journey. You see what works with others, what resonates and why. That is where I find myself interacting. Life is kaleidoscopic, and varied perspectives from people throw light on things that one perhaps otherwise hasn’t considered. Then again, too much of it can lead to confusion, and so finding a balance of information and dialogue is healthy. Beyond that it is better to be more private, in my case.

Are there any books or films or music in which you identify yourself and your work?

Identity itself is so fickle and therefore it’s hard to say which ones I could potentially identify with. I love mythology, storytelling anthropology and folklore. I love people’s personal tales too — they resonate a lot with me.

What, according to you, defines the success of a performance?

Honesty and vulnerability, as well as a good editing process and very good sound design. I prefer wanting more than wishing the show were over!

What are you working on next?

I am currently working on very exciting productions: one is called Drumming a Dream — a Children’s Musical Theater in New York — based on an Indian folktale that tackles issues of diversity, trust, courage and immigration. It has a cast of eight actors, all from varied backgrounds, and includes Afro-Cuban tap dance, Indian dance and music as well as contemporary theatre and dance. We had a residency at the prestigious New Victory Theater on Broadway in New York and are now looking to complete the work. I can see it as the next major holiday show which includes the many multicultural voices that make up our society today.

The second production is titled L’Orient. We are imagining this as an interactive theatre experience for 2021-22 playing on the classical (ballet and Bharatnatyam, opera and Carnatic). It looks at the 19th-century opera Lakmé by Leo Delibes and a 21st-century relook at the gaze of the west on the east. Another project which is very dear to my heart is a journey between myself and Amar Ramasar, principal dancer from the New York City Ballet. It is called Letters and is based on an almost four-year-long relationship between us and our work revolving around personal stories and our recent journey to India to rediscover our heritage through each other’s eyes. It’s about finding ‘home’ and where that resides.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)