In 2010, while researching my first book, The Ivory Throne, I came across an 1877 letter by a scholar celebrated as the Kalidas of Kerala. His name was Kerala Varma, but the lines in this letter were neither Sanskrit poetry nor a Malayalam composition. The whole thing was, in fact, a privately written confession of his sins, and among the “heinous” offences he claims to have committed, he lists an interest in Christianity, exchanges with journalists — and “the intemperate use of Bhang” and “stronger narcotics”.

I remember sitting up with wonder. Historical figures often seem to exist in a universe that isn’t quite human. One learns their tales in school — their successes and defeats on the battlefield, their struggles against imperialism, their pious motives and selfless contributions — but rarely do they feature as simply men and women. Kerala Varma is, in textbooks, the Father of Malayalam Literature. But what about the man who, like the young even today, spent his twenties pursuing the ingredients that go into bhang?

From the start, my interest in history was connected to a curiosity about the men and women who animated its stories. How did they think? What were their motivations? They said they had lofty goals, but what hidden compulsions were in play? Who lost out, and who prevailed? Where did the loser go? What does an old text tell us? And what, significantly, does it omit? Ultimately, how is it that men and women of flesh and blood became monochromatic “figures” who made our past but, in equal measure, haunt and inspire our present?

I had endless questions, and the answers appeared in tantalising glimpses. Often they appeared in the form of even more questions. As I traced the life of my protagonist Sethu Lakshmi Bayi — a queen who lost her kingdom and died in oblivion — I sought out paper: letters, records, intelligence reports, diaries, newspaper features and much more. From this I learnt of her policies and politics; what the band played on her thirtieth birthday; that she sat with a lemon at banquets and could not eat with foreigners; and that Gandhi praised her while Lord Willingdon deceived her.

I also looked for people: daughters, nephews, correspondents, and even nurses who washed her when she was old and infirm. They told me of her sense of humour, her arthritis, her joys and regrets, her love of roses, her empty bank account. The papers presented the historical “figure” and how she left her mark on society; the people who knew her remembered the woman she was, whose life was marked by dignity as well as tragedy. Sometimes lines were blurred: yellowing files informed me she once had tuberculosis. Her own daughter did not know.

To be truly curious about the past is to subject it to a relentless interrogation. It challenges notions one holds dear, though one equally risks the confirmation of other prejudices. Only an unwavering stream of questions can steady the boat. At times it can even hurt people. I discovered, for instance, that the grandmother of my protagonist was “addicted to drink”. It upset some of her descendants who vehemently disagreed — but, quickly I asked, why does alcohol diminish her memory at all? Before she became an ancestor, was she not just a person?

Curiosity about the past begins with liberating it from present limitations. The past exists on its own terms, not to assuage guilt today, rouse passions tomorrow, or to pat ourselves on our backs. The achievements of those in the past do not excuse our failures, though history’s failures can often be our shame. To be truly curious, though, is to leave all that to the side and see from the eyes of those who were there: what they say, how they saw it, and why they did what they did. We can learn and we may seek inspiration. But at the end of the day, curiosity and the past are both about questions.

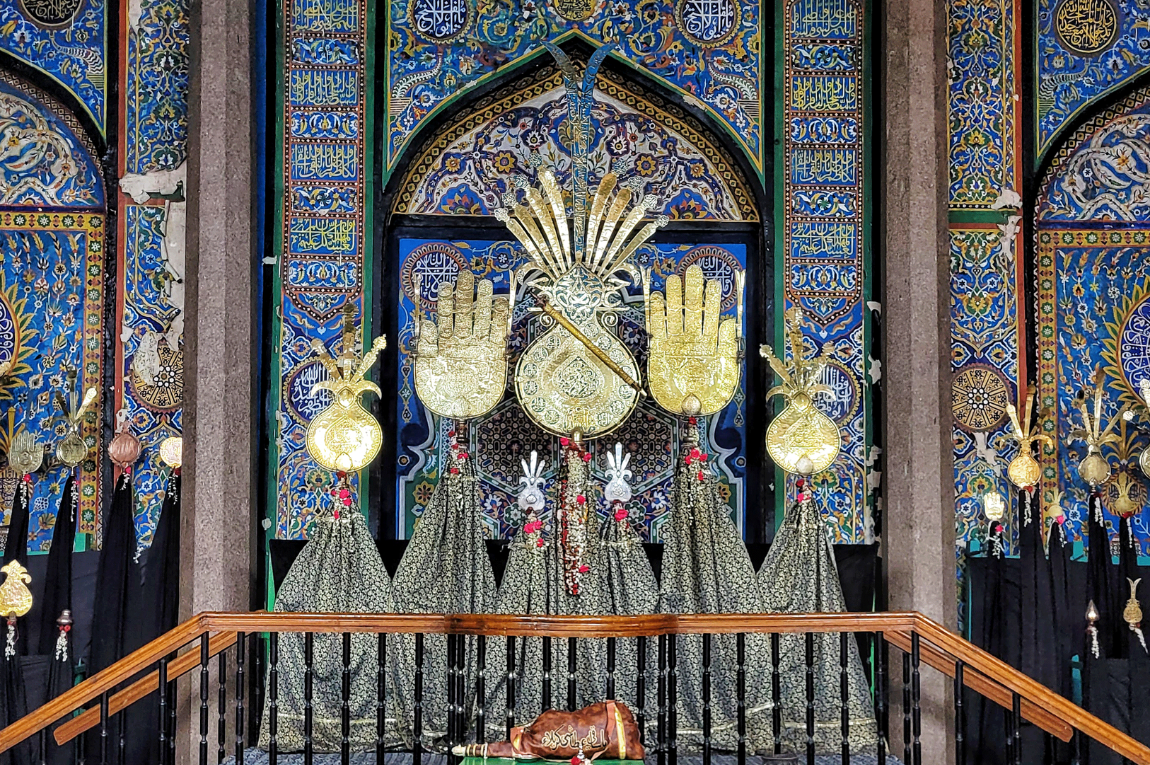

Manu S Pillai is the author of the award-winning The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore (2015), and Rebel Sultans: The Deccan from Khilji to Shivaji (2018). He writes a weekly column for Mint Lounge, and his writings have appeared in publications such as The Hindu, Open Magazine, and The Hindustan Times among others.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.