Not long after the start of India’s COVID-19 lockdown in March, images and videos of what would come to define the country’s quarantine in the world’s eyes began to haunt our social feeds. It was an exodus of migrant workers across our biggest cities — hungry, stranded attempting to return to remote hometowns in the absence of public transport services. Recent reports point to hundreds dying not of the virus itself but as a result of a poorly planned lockdown.

As an emerging and developing country, India is well aware of its socio-economic challenges — we have the world’s second largest population with a high burden of communicable disease. The coronavirus crisis though, has given our vulnerabilities centre stage, creating an urgency to re-examine the way we create and consume, live and work.

Behind the Scenes

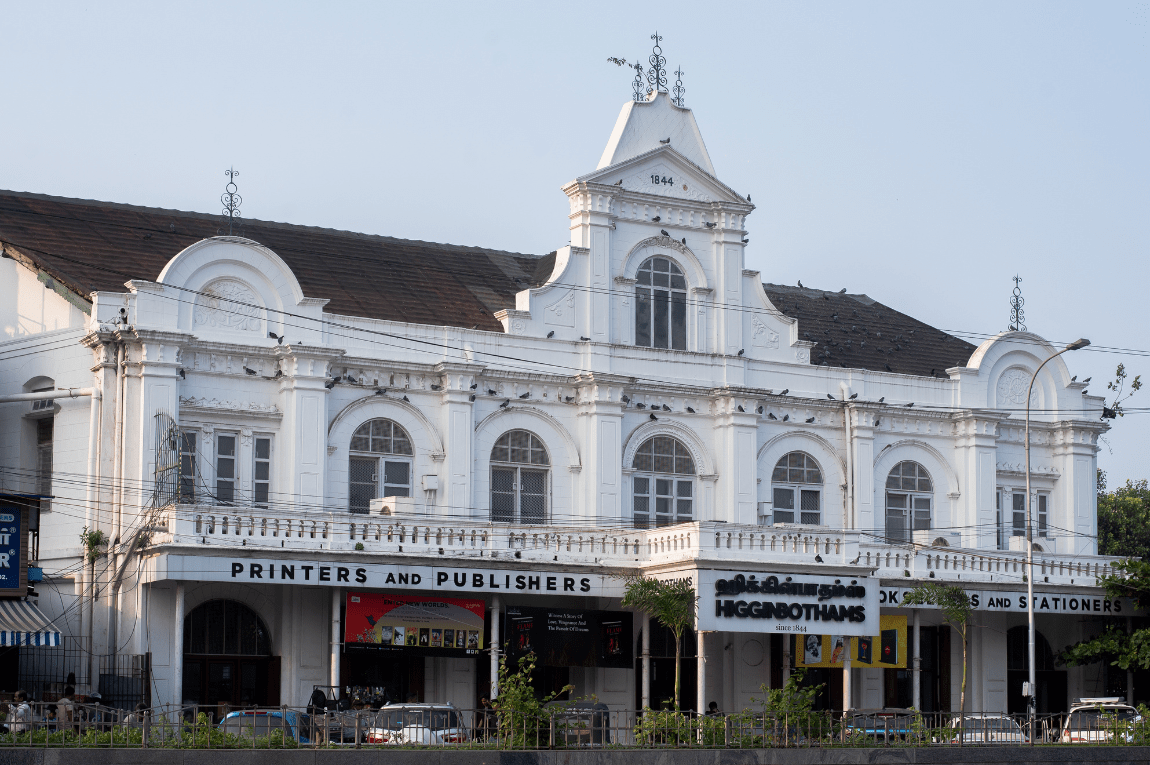

In an Indian context, design is largely perceived as a linear process between company and consumer; a means to enhance the economic value of a product or service via form and function. In light of the pandemic though, it’s imperative to relook at the entire ecosystem of unorganised workpeople that facilitates design.

Reviewing the migrant worker crisis, AGK Menon, a Delhi-based architect, urban planner and conservation consultant, explains how the capital’s long-standing slum problem is part of a wider urban design and financial planning issue. “We only designed the planned part of the city. The people who built it live in the unplanned part, creating slums,” he says, emphasizing a need to include aspects beyond material costs — like fair wages, labour housing support and financial insurance — in a project’s overall budget.

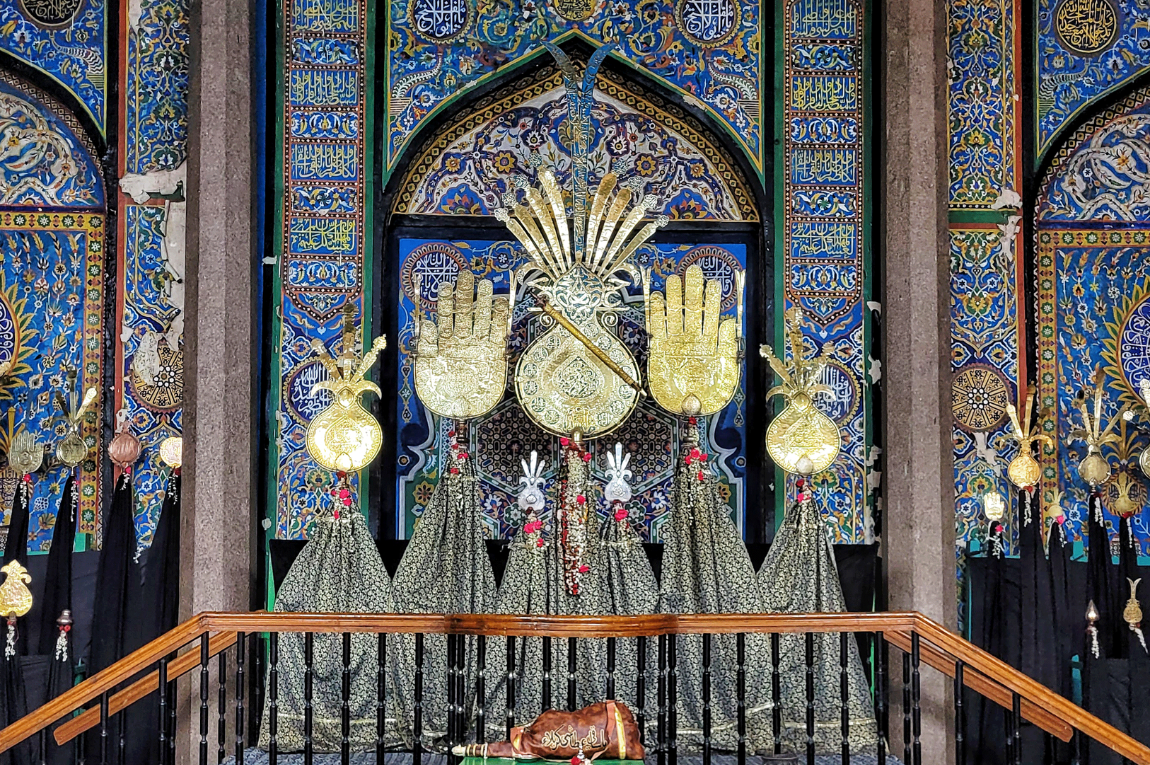

Inclusivity can be more of an uphill task in sectors like handcrafted product design that compete in a market of industrially produced goods. “Over generations, traditional practices have been exploited to cater to the market for profit; craftspeople are not valued for their knowledge but only skill. People want handmade products to be cheaper, which doesn’t justify it,” says Sandeep Sangaru, a Bangalore-based multidisciplinary artist who has been actively engaged with the decentralised craft sector via his studio Sangaru Design.

A World, Revised and Updated

At an individual level, the lockdown has spurred a period of introspection. While the concept of slow living isn’t new, we’re realising that it is indeed possible. What’s more, we’re seeing its positive impact on our work-life balance and the external environment at large. India’s Central Pollution Control Board notes that the Ganga’s water quality is improving in industrial towns and that Delhi’s PM10 air pollution levels reduced by up to 44 per cent on day 01 of the curfew. In Jalandhar, Punjab, snow-capped Himalayan views have been spotted after decades.

These reports offer immense promise. “It goes both ways — the gains that we’ve made in this period are equally reversible in a matter of days. But if we know this damage is reversible, that optimism can make us do great things,” says Ayush Chauhan, co-founder of Quicksand, a design research and innovation studio. He highlights the urgency for macro institutions, like national governments and intergovernmental bodies, to re-examine societal goals and the state of the economy under the lens of a clean energy future.

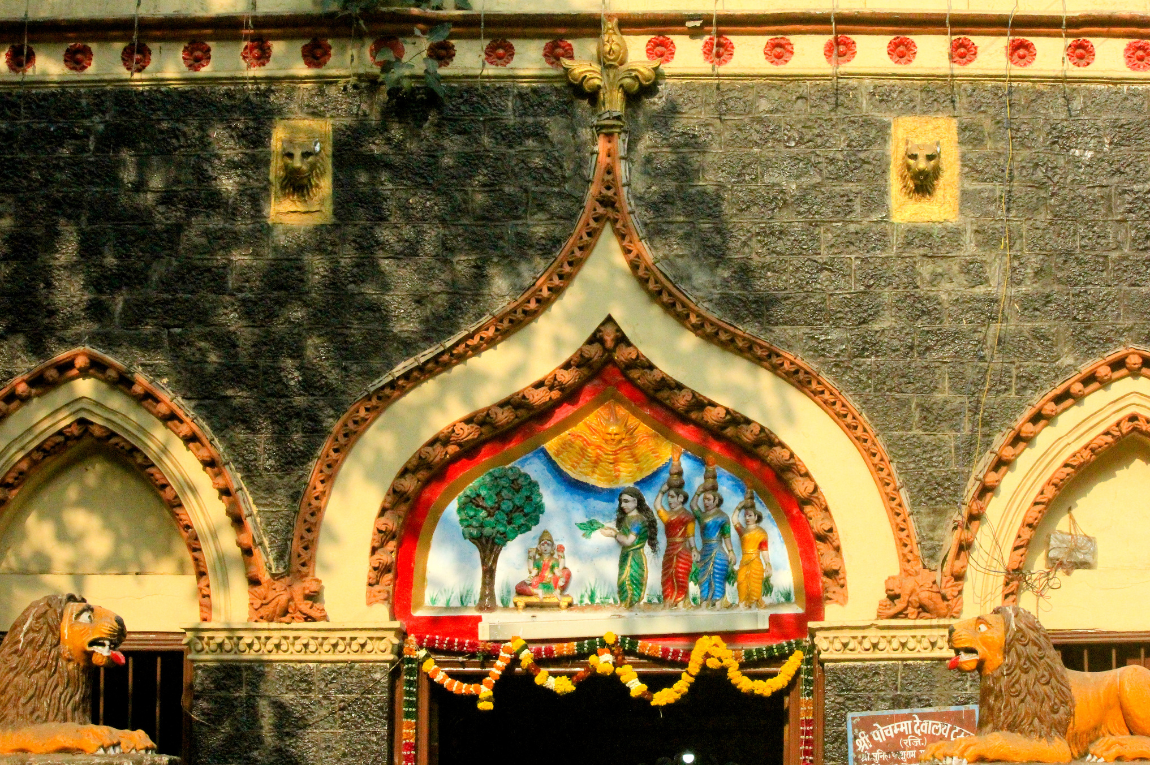

A sudden drop in consumerism also comes with consequences. Sangaru cautions that it could have a detrimental impact on the labour that relies on these industries for its livelihood, and that the system on the whole needs rejigging. “When you concentrate everything at one point, it’s like a cancer; large factories need lots of resources at that point of time,” he explains. But instead, “if we break the fundamental process of production into smaller units, then we’ll use lesser resources in small pockets. You’re producing the same numbers and employing a larger number of people spread across the country.”

The onus in this future would fall on the consumer too. Creating valued goods with extended life cycles could certainly mitigate the throwaway culture, but in a country where design is often looked at as a status symbol, Menon questions our readiness for sustainable, frugal offerings that will be markedly different from what we’re used to.

A Way Forward

The closing of international borders and a slowing down of world economies raises questions on how we do business. Could the pandemic be an opportunity to understand our capabilities as a self-sufficient state? “This crisis provides the tailwind for some form of deglobalisation,” says Chauhan. “We’ve been washing our hands off the kind of negative externalities that global trade has created. It nudges us to make our internal economics and systems stronger.”

Menon adds that post-pandemic policies must tow the fine line between economic nationalism and global cooperation. While more authoritarian controls are in the offing, he says, “The challenge for designers and policy makers of the built environment, at least, [is to] simultaneously ensure that these initiatives are democratic and promote the social values of our society.”

Much of the change we speak of relies on large policy decisions by macro institutions . At a fundamental level, it mandates greater equity and ethics, increased spends on healthcare and education, a universal basic income, et cetera. Ideally, this would also enable sustainable behavioural change at the individual level.

Sangaru stresses on the need for a design-inclusive policy-making process. “Design is about creating a better way of life. Designers have always been trained to design [by] looking into issues of communities at a macro level, and then getting into the micro level to create a solution for a particular need at that particular point of time,” he elaborates, drawing parallels between Scandinavia’s design-led innovation in governments.

Quicksand has been mining its past research on epidemics like the Ebola and Zika crises, in an attempt to share knowledge with organisations at the frontlines that are trying to figure a response for vulnerable groups. Chauhan admits that it’s hard for individual design firms to influence the government at the moment, but he is hopeful that interest from the global public health and international development sectors can indirectly achieve this.

He points to international catering company Compass Group India’s #LetsFeedTogether initiative that has teamed with a host of NGOs, government bodies and private companies to deliver meals to marginalized communities across five metros. Then there’s Pune start-up NOCCA Robotics’ low-cost ventilator (a prototype) that wouldn’t be possible without swift public and private sector support. “These are responses to a crisis, but this is the collaboration that we need at a societal level, this is the compassion that capitalism needs to embrace, this is also the agility that governments need to have,” says Chauhan.

Over the last decade, we’ve witnessed a gradual return of design to its human-centred core. There’s never been a clearer call for the fraternity to own this — as trendsetters, to serve as knowledge pools and agents of change, and as creative storytellers, to construct a narrative built on compassion and hope.

Gretchen Ferrao Walker is an editorial consultant who has collaborated with Indian and international publications like GQ India, Forbes India, Time Out, Architectural Digest India, Design Anthology and Collectively.org. She is the former editor of travel bimonthly Time Out Explorer and current mum to a 2-year-old. She enjoys embroidering and making pictures.

Madhav Nair is Senior Designer at Paper Planes. Most of his work as an illustrator and graphic artist is published under the pseudonym @deadtheduck.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.