Author Mridula Koshy started The Community Library Project (TCLP) in New Delhi in 2014-15 with her partner Michael Creighton, in collaboration with the NGO Deepalaya and Narang Trust in a working-class neighbourhood with the intention of creating a free, inclusive, citizen-led, and publicly owned space for all to access books. Her collection of short stories ‘If It Is Sweet’ received the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize in 2009, and she has, since then, written several books including ‘Not Only the Things That Have Happened’ (2013) and ‘Bicycle Dreaming’ (2016). Koshy tells us why books are a powerful tool for thinking, why Sunday is her favourite day of the week at the library, and how writing allows her to revisit the memory of a momentary, fleeting experience.

What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I am reading Tony Joseph’s Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From. I revisit Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat and Anna Karenina as well as William Faulkner’s The Sound and The Fury and Agha Shahid Ali’s Postcards from Kashmir. Actually, lately, all I do is revisit; the list is long. I find it difficult to read and one solution to this is to reread.

What did you grow up reading? Is there a book you wished you read as a child? And what was your relationship with libraries like?

I grew up with the Bible but more as a work of literature, as an ocean of stories and a poem of great breadth than as a religious text. Inevitably, my spiritual life and not just my literary self is formed by it. There was a giant ‘family Bible’ in my house. There was sporadic access to libraries.

When I was in class eight, for reasons that did not have to do with carelessness, reasons that were beyond my control, I successively lost three books from my school library. It was a terrible library in many ways — closed shelves, no free choice of books, a librarian who selected the books we could read, and a didactic and moralistic collection. I was banned from the library and had to remain in the classroom when once a week the other children formed a line and left the class for library period. I felt frightened sitting alone in the classroom. I would try to hide because every passing teacher would come in and ask why I was there alone and then proceed to berate me for the sin of being human, for losing books. At the free library I run now, we don’t impose fines for misplaced books or books returned late. This is not because of my experience but because it is cutting-edge, good practice. However for me, personally, the policy is healing. The reason I lost books over and over that year was because someone who was abusing and harassing me was stealing and getting rid of the books to get me punished.

Do you tend to latch on to certain themes in your writing or is it easy to let go of them?

I latch on to an image, something I have seen, something enthralling, something that lifts me from this world, something that transports me beyond the loneliness of my singular experience. It is sometimes as simple as a glimpse of two people together, or a child running toward something unknown. The problem with seeing something transporting is the momentary and necessarily ephemeral nature of the experience. Writing allows me to revisit the experience, live it again and turn it in my hands to see it from different angles, to extend it in time.

Do you ever end up with nothing left from earlier drafts? If not, then do those fragments find their way into a subsequent work of writing?

I hate wasting effort. If I write something and it doesn’t work — for example as a chapter in a novel — I definitely try to salvage it and turn it into a short story. Though there are times when no amount of effort can salvage a work.

Before returning to Delhi, you worked in the United States as a trade union activist and community organiser. Could you tell us more about this role? Did the intention of working with the community stem from here?

I worked as a trade union organiser in my early to late twenties. It was a period that formed me, especially politically. I am interested in the question of who has power and how we can redistribute it. My work then allowed me to see power shift from one side of the table — the boss’ side — to the other side, which is the workers’ side. Certainly the work I do now, which involves building an organisation that advocates for all people to have access to books, is a continuation of that past experience of organising for power. I understand better now as I begin the fifth decade of my life that much depends on history. We have an organisation that serves a few thousand people, has built four libraries under our own banner and assisted in building many others with and for several organisations. All of this would remain in the realm of social work if not for the fact that we also serve the political idea of building access for all. However, what it would take to catalyse this into a mass movement is beyond the power of any one organisation. Here is where we can hope for history to be on our side and hope for other organisations with whom to work.

You started The Community Library Project (TCLP) with the aim of creating a free, inclusive, publicly owned, thriving space for all to access books, language no bar. What was the initial response like?

Very simply, the people came. If it is free, if it is not mediated by money, then it is revolutionary, then it is freeing. People came because they saw a space which is a little better than the world in which they live, one where we all meet one another as equals. It’s lovely that the space is full of thousands of books and there is a chance to read, meet and talk about ideas. Books are a powerful tool for thinking, and people who think with books are more powerful than when they think without books. Moreover, people who think with other people and with books are the most powerful thinkers. Those who came to us initially were mostly children. Many are now grown — I expect great things from them.

In a previously published article you’ve stated that you became a writer by first becoming a reader, and that you became a reader for the simple reason that you found your way to a library and to the books within. Was this thought always, somehow, associated with your idea of sowing the seeds for TCLP?

It is horrifying to imagine a life in which I did not have access to libraries. Books have saved me, again and again. They have literally given me reason to live. So when I think about the majority of people in India not having access to this life-saving good, I feel I need to do something about it. If even a few people who gain access to reading through our library movement go on to become writers, Indian literature will grow and change radically. That will be a bonus.

The ongoing sit-in protests in New Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh have fostered a community reading corner, a reading space for discussion and reflection. How important do you think is reading as a form of protest?

We are a country that builds highways, stadiums and airports in a bid to declare that we have arrived. But we don’t build libraries. We provide schooling for all in a bid to ensure we have a workforce that is competitive in the global economy. But we don’t build libraries. It doesn’t take a lot to put two and two together and realise a long history of exclusion is still here with us today. Our history of being colonised, the education system it foisted on us, the longer history of the caste system, of patriarchy, and of class, is a history of excluding people from reading. We want only the most basic literacy for the majority of India. We do not want the kind of critical thinkers that are fostered in libraries. So yes, the protest libraries springing up all over Delhi as part of people’s revolt against exclusion is heartening; reading is a means to protest.

What does a day of work at the library look like for you?

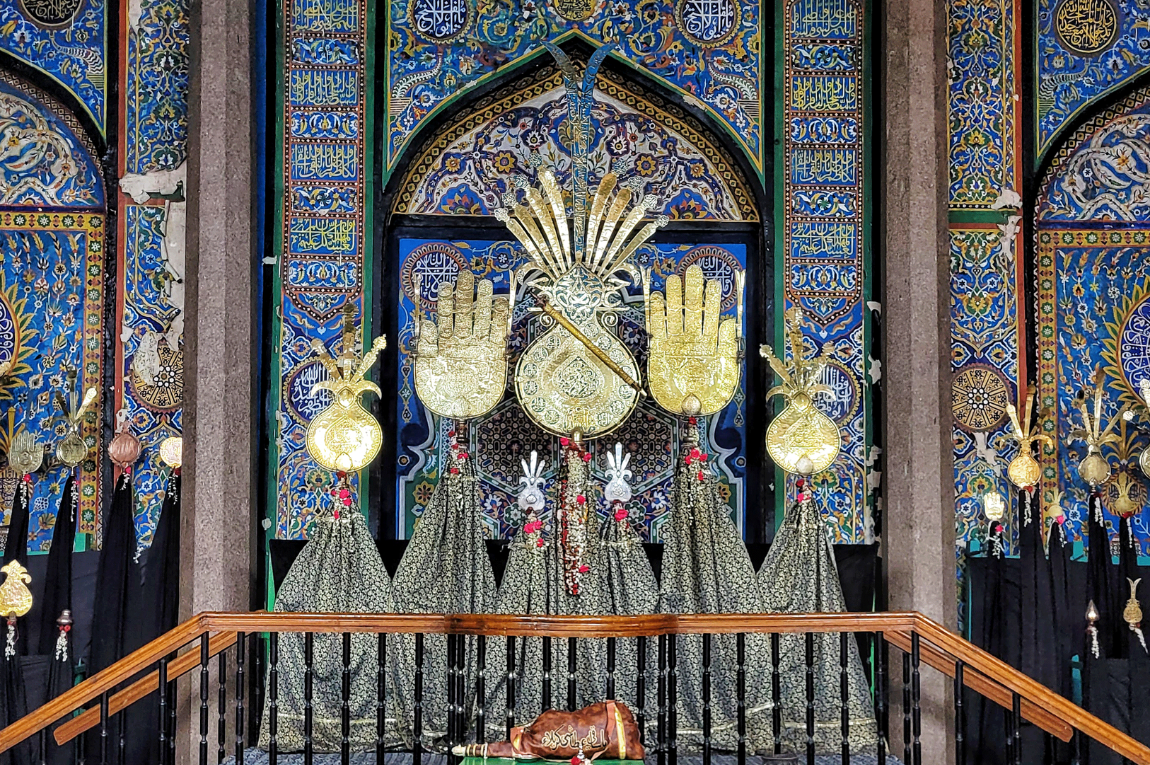

There are no typical days. However, my favourite is Sundays at the Sheikh Sarai branch [of the library]. It is the day when the Student Council runs the library. The Student Council is composed of young people ranging in age from their teens to those in college. They are key to ensuring the warmest welcome to the even younger people and some older people who come into the library. The Student Council members issue books at the circulation desk, do read-alouds for the little ones, conduct the weekly assembly where typically at least one, and sometimes three or four, members are applauded for entering into the ‘100 Books Club’, set out chess, checkers and carrom for the Game Room, oversee the Cyber Project which allows members access to computers and the internet, and when it is closing time, they extract a report from Koha (a library software) on how many members have issued books, they affix stars on the Honour Roll next to the names of children, each star denoting ten or more books read, and they re-shelve books and sweep the floor. When two younger members, aspirants to the Student Council, argue over who should be allowed to press the lock shut on the door, they step in and settle the argument by asking the two to take turns! Most Sundays we see between 150 and 200 people. Some of our members come in and out a dozen times. Member leadership and ownership of the library in the form of the Student Council is critical to this level of participation and love for the library. I mostly bask in all of it and when I am not basking I am stressing, mostly over funding for our work.

The role played by the members of the Student Council at the libraries is indeed very crucial. How do they go about ensuring and facilitating that the children who access the books not only read them but also grasp and question what they are reading, express themselves, and even perhaps draw parallels to their own lives?

Members of the Student Council have grown up reading and being read to in the library. Many are gifted at reading in a natural voice and inviting the little ones in the circle to think about what is being read. They will ask the circle of listeners, “What do you think is going to happen,” and then turn the page and if something surprising has happened, they will express surprise. The Student Council is trained so that even those who are gifted at read-alouds understand why it is that a read-aloud works to invite the hesitant reader who is lacking in fluency to enter reading and experience the pleasure of thinking while reading.

It is important to accept that providing people access matters more than checking to see if they are reading. What will we do if they are not reading — punish them by removing access? In our own homes and among the middle and upper classes, we celebrate the acquisition of books that are never read. This is a kind of luxury we allow ourselves presumably because we merit it. If we can allow that we will not read all the books we purchase, then we can allow that library members will not read all the books they borrow. Once we accept that access matters, then we can look at the question of what practices and methods help people read. Read-alouds do help people read.

Do you think it is critical for writers to engage with the society in ways that involve giving back, or sharing their knowledge and skills?

Well, if we want a robust literature, one in which our writing sits side by side with tens of thousands of other titles that together create a lively conversation of ideas and critique, then we definitely need to do more than just write. We need to engage with the question of how we can build that literature. Building libraries is fundamental to building such a literature.

What are the most pressing challenges you face while running the project today?

We are constantly scrambling for funds.

Apart from the collection of books, what are the other elements that make a good, inclusive library?

Free membership. Free membership. Free membership.

In The Community Library Project, we no longer call for a ‘library movement’. Instead we call for the ‘free library movement’. By free, we mean no sliding scale membership; no free memberships for those who are poor and paid memberships for the rest; no free libraries for the poor that are poor libraries and rich and excellent libraries for those who can afford them. Additionally, no late fees or fees for lost books, or security deposits or charges for attending special workshops. At least in the library we must remove the book from the marketplace. It is not only what we owe our most powerful thinkers like Kabir or Ambedkar but also what we owe every one of those who have read these writers over the centuries and decades and kept their ideas alive, so that we can access them today. It is what we owe those who wish to read books and think about the ideas within, and it is what we owe ourselves, we who wish to divest ourselves of the privilege to read a poorer and poorer literature every year and to live a poorer and poorer life bereft of a relationship with our brothers and sisters in the working class.

(Note: When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small affiliate commission.)