There’s a lot that makes up the Mumbai we now know. From the skyline to the streets, there have been several contributions to how the city is shaped. But what of the ideas that never came to be? A new book — Bombay Imagined: An Illustrated History of the Unbuilt City by architect Robert Stephens — is a collection of 200 unrealised urban visions, starting in 1670, right up to the 21st century. These aspirations include humane housing, expanded parks, sanitation systems, and more. The ideas are richly illustrated with archival drawings, contemporary speculations and artistic overlays, illuminating long-lost futures from the city’s never-before-seen past.

Read on for four excerpts from the book.

1777 — Sea Outfall

Lawrence Nilson

In 1777, Principal Engineer Lawrence Nilson penned the first recorded break from Bombay’s laissez-faire attitude towards sewage management, writing, “The foulness of the ditch [surrounding the Fort Walls] will ever be very great and the water thereof very offensive to the inhabitants, while the common sewers of the town are suffered to discharge themselves into it. I would therefore propose that sewers be made to discharge themselves into the sea.”1 Intrigued, sanctioning authorities with their hands on the purse strings asked for a cost estimate, only to quash the exorbitantly priced proposition 30 days later. In a last-ditch effort to prevent Bombay from being routed by its own faecal matter, officials floated a reversal to Nilson’s proposal — rather than taking the sewage to the sea, why not bring the sea to the sewage? In the days of experimentation that followed, high-tide waters were successfully directed into the putrid channel, although the entire exercise failed when sluggish drainage at low tide left behind metres of septic silt.2 The ditch would remain a receptacle of muck for the next 85 years, before being buried in an avalanche of debris from the Fort Walls, thanks to the destructive decree of Governor Bartle Frere.

“The town ditch is now so very foul as to require to be thoroughly cleaned…. entertaining fifteen hundred labourers for that purpose.”

—Lawrence Nilson, 1777

1 Lawrence Nilson, “Letter to Government,” Pub. Diary 71 of 1777, March 26, 1777, in JM Campbell, Materials Towards a Statistical Account of the Town and Island of Bombay, Volume II (Bombay: Government Central Press, 1894), pp. 406-407.

2 Ibid., p. 408.

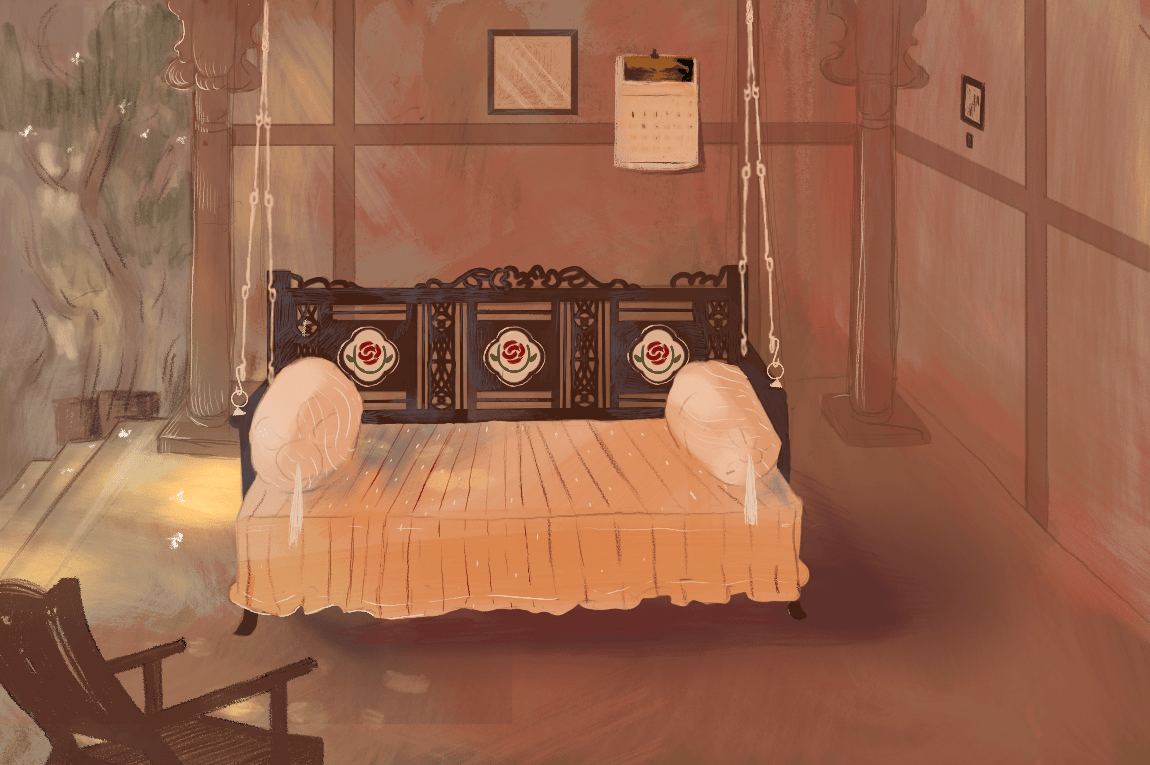

1864 — Versovah Suburbs

Walter Ducat

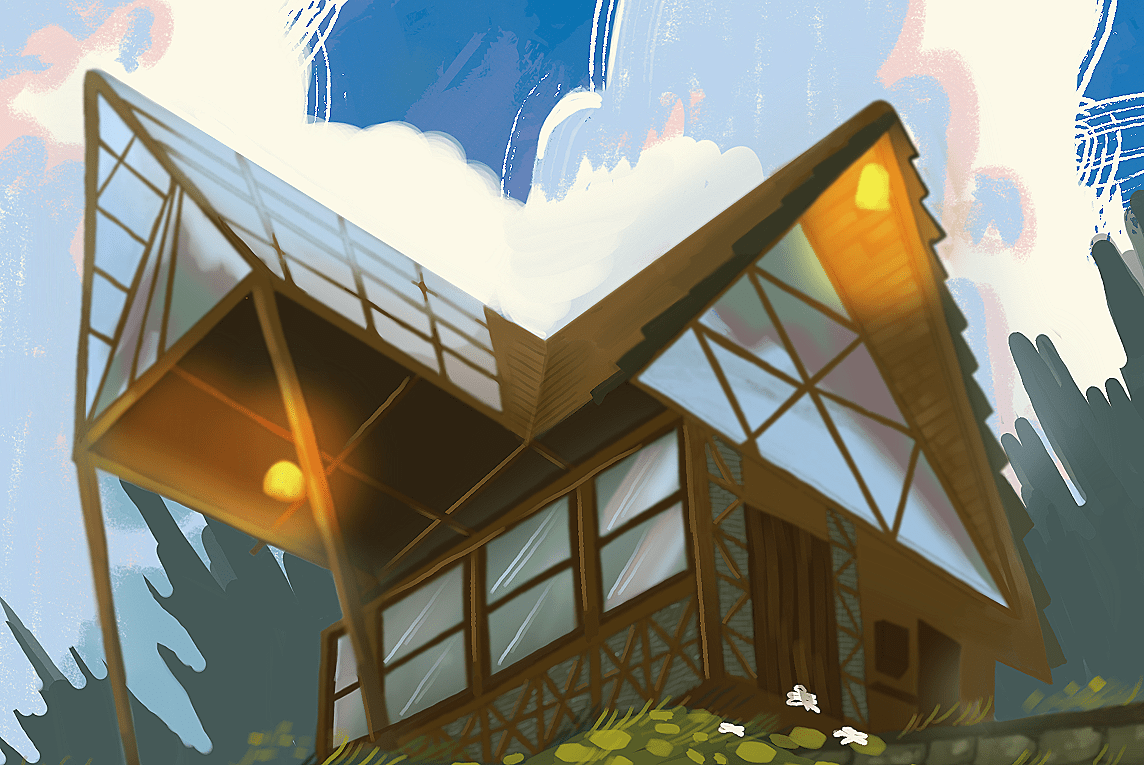

A new railway over Malad Creek was to provide access to Ducat’s suburban development at Versovah. Speculative illustration by Aniket Umaria.

Executive Engineer Walter Ducat’s report of 1864 titled “The Suitability of Versovah as a Suburb to Bombay” must have conjured shock and awe among its readers. While every nook and cranny of the Island City’s southern tip was being jammed with speculative reclamation and dock schemes, Ducat trekked 17 miles northwards through the countryside to Versovah, and imagined an idyllic residential enclave. Spread over nearly 200 acres of salubrious terrain, the proposed layout featured 82 villas, markets, shops, a church and a 60-acre public park.1 Access to the seaside suburb was to be provided via a four-mile-long branch railway from Andheri and a bridge over Malad Creek, an infrastructural ambition which continues to be pursued well into the 21st century.2 Like many speculative schemes at the time, the proposal had it all, simultaneously having nothing.

In a moment of objective reflection, Ducat confessed, “Without the railway the buildings are useless to Bombay, and without the houses the railway would not pay.”3 Neither would materialise in Ducat’s lifetime, and it would take a plague at the turn of the century to force a renewed exploration of possibilities for suburban living in Versovah.4

“The hills at Versovah are large enough to maintain good markets and shops, its own church and clergymen, and to possess all the advantages of a small town in itself.”

—Walter Ducat, 1864

1 Walter M. Ducat, “Suburbs for Bombay,” The Bombay Builder, Volume I (Bombay: The Office of the Bombay Builder Mechanics Institute, 1865), pp. 184-186.

2 Linah Baliga, “Bridge to Madh makes headway after 10 years,” Mumbai Mirror, February 14, 2020.

3 Ibid., 1: p. 185.

4 PJ Mead, Report on the Possibilities of Development of Salsette as a Residential Suburb (Bombay: The Government Central Press, 1909).

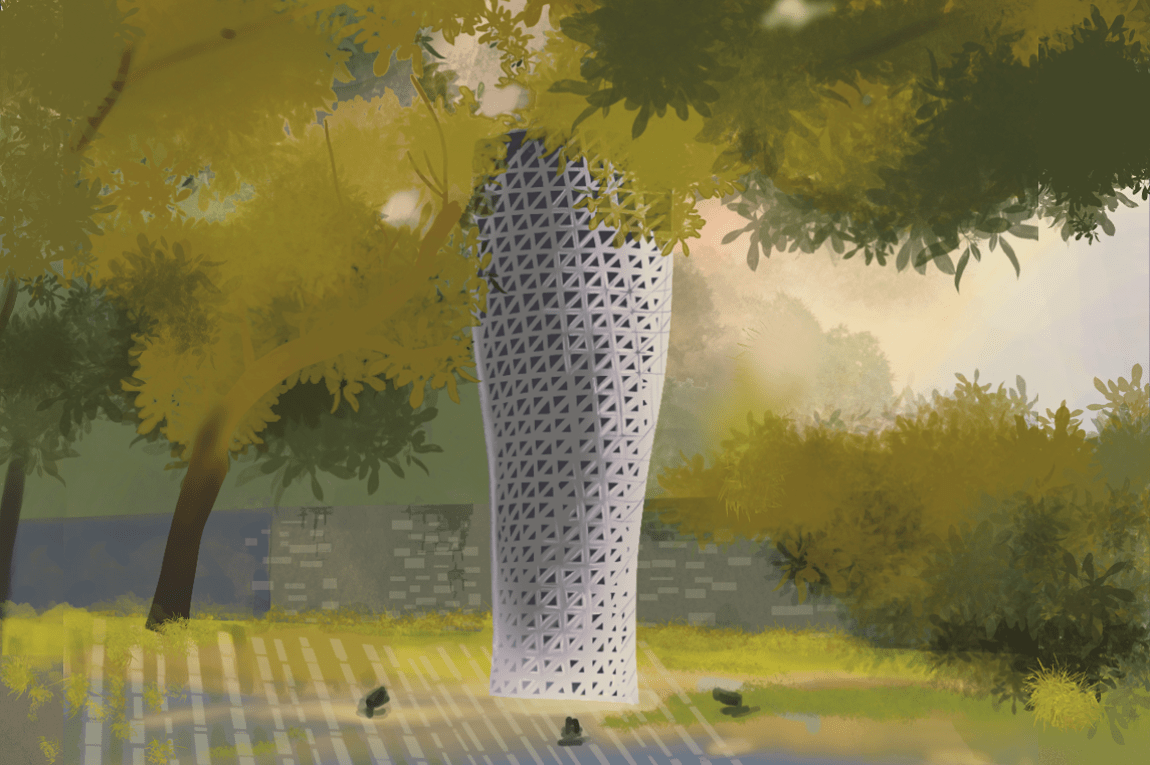

A dreamy vision of South Bombay as seen through a flood of aerial taxis. The new, centrally located Back Bay Park was to be flanked by Malabar Hill on the right and Nariman Point on the left. Speculative illustration by Akhil Alukkaran & Fauwaz Khan.

1921 — Bombay 1971

Anonymous

Nobody let their imagination of future Bombay run as wild as an anonymous creative, whose prose of 1921 painted a dramatic vision of the city 50 years hence. The surreal journey commenced at Malabar Point’s Government House, transformed over time into a people’s pleasure ground from which the complete reclamation of Back Bay lay on full display. An array of fine buildings dotted the previously non-existent horizon, with “curious landing stages from which aircraft were constantly ascending.” Swarms of silent aerial taxis flooded the skies, while broad, shaded, dustless, and perfectly surfaced streets brought a new order to the previously chaotic roadways. Subways with escalators dipped safely below the flow of electric cars as centrally located travelators whisked pedestrians along at warp speed. Subterranean lifts offered seamless connection to an underground tube “the coolest place in the city.” Bigger and better docks reshaped the Eastern Foreshore, while the Western Foreshore had become a recreationist’s paradise with “hundreds of bathers riding the surf as at Sydney.” Time was never of the essence as new government statutes restricted the workday to a mere four hours, and landlords were abolished. Astonished, the anonymous visionary inquired as to who was responsible for the transformation, only to be woken shortly thereafter, recounting, “I had fallen off the seat on which I had gone to sleep on Malabar Point and had rolled down the slope. Only the railings had stopped me from falling into the sea. I staggered to my feet and looked wildly around. Yes, I had been dreaming. Sadly, I wandered back home to my comfortless room in my comfortless hotel past the series of dumps on the sea face which represented man’s puny efforts to make Bombay the paradise I had pictured.”1

“Everywhere order and cleanliness. It seemed to me that a wizard wand had been waved over the slum district that I had known.”

—Anonymous

1 Author Unknown, “Fifty Years Hence, A Dream of Bombay,” The Times of India, October 12, 1921.

Feng Shui expert Lillian Too advised Mumbai’s residents to fit out their windows with antique cannons and oversized mirrors to deflect negative energy radiating from the proposed flyover. Speculative illustration by Aniket Umaria.

2001 — Peddar Road Flyover

Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation

“Like a humongous roller coaster slicing through the narrow Peddar Road lined with residential buildings,” is how one observer described the proposed four-kilometre-long flyover from Haji Ali to Wilson College.1 Not surprisingly, the rupees-150-crore scheme made many sick, including playback singers and Peddar Road residents Asha Bhosle and Lata Mangeshkar, who threatened to relocate to Dubai if the elevated highway rose before their eyes and ears.2 Bands of equally perturbed residents joined the chorus, arguing that the concrete viaduct’s trapping of noxious vehicular emissions would transform one of Mumbai’s most posh neighbourhoods into a “living hell.”3 In defence, the Maharashtra State Road Development Corporation contended the proposal would lubricate the high-friction stretch and increase traffic speed from a piddly 14 kilometres per hour to a brisk 40 kilometres per hour. In mid-2016, after 16 years of relentless protests, the high-flying proposition was finally scrapped by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation in light of another up-and-coming palliative, the Mumbai Coastal Road.4

“The government is helping the elite by building flyovers.”

—Veena Singhal, 2001

1 Times News Network, “MSRDC projects vision of future for Peddar Road,” The Times of India, April 6, 2002.

2 Radha Rajadhyaksha, “Lata and Asha are not singing out of tune, say environmentalists: Anti-Peddar Road sentiment has obfuscated the real issues,” The Times of India, March 31, 2002.

3 S Balakrishnan, “Govt is helping the elite by building flyovers,” The Times of India, May 14, 2001.

4 Ateeq Shaikh, “Peddar Road flyover plan scrapped, finally,” Daily News & Analysis, June 3, 2016.

Bombay Imagined, An Illustrated History of the Unbuilt City is now available for pre-order on www.urbsindis.com.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.