At the recently launched FC Road Social in Pune, designed by Mumbai-based practice The Orange Lane, a garden theme springs to life. The centrepiece, a 24-foot-tall mural by Serbian street artist Artez, features a monstera-headed protagonist against a monochromatic palm frond backdrop.

In Mumbai, interior designer Minnie Bhatt conceptualised Ishaara — a new, sign-and-dine restaurant — as a conservatory, replete with living greenscapes and custom-printed botanical wallpapers.

Hyderabad’s film production company Matinee Entertainment comes with an outdoorsy design by Sona Reddy Studio that showcases line art of flora and fauna along walls and ceilings — a nature-inspired reinterpretation of palace and cathedral architecture.

Undoubtedly, we’re more expressive of our obsession with nature than ever before. It’s something that Shabnam Gupta, principal designer at The Orange Lane, acknowledges, but she also emphasises that botanical art is a leitmotif that goes back centuries. “People are just reinventing the application. It’s probably used in far more mediums now and we’re just noticing it more,” she says.

Earlier this year, art quarterly Marg chronicled the country’s botanical art journey with its issue, The Weight of a Petal: Ars Botanica. As the tome illustrates, our love of leaves stretches beyond the scientific scope of the artform. Geetanjali Sachdev, a Bengaluru-based, art and design pedagogue at the Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, elaborates, “[Plants] travelled into art through different influences… ancient folk art practices [like warli paintings and Orissa’s wall art], visual depictions of Hindu religious texts, foreign cultures like that of the Mughals, and later the Europeans.”

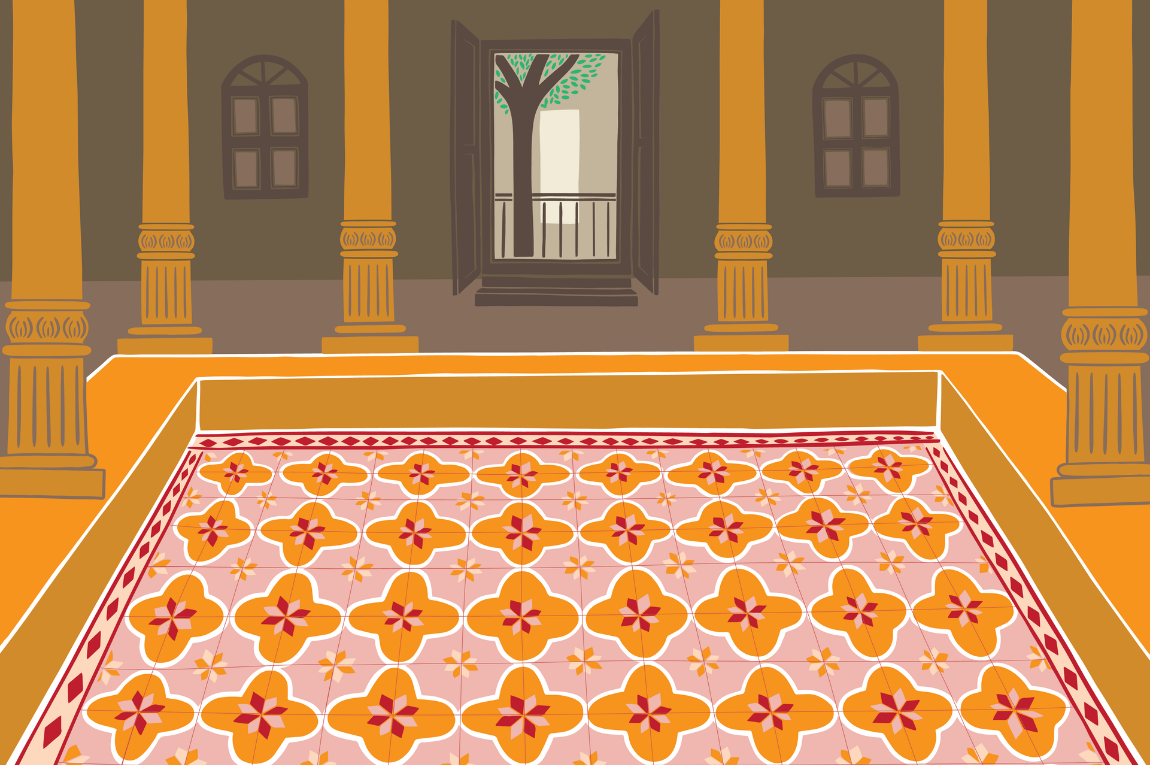

Historically, India’s art is linked with religion. The puranas are rife with references to plants, which were revered for their role in sustaining human life. Citing temple sculptures from the Hoysala Dynasty, which ruled between the 10th and 14th centuries, Sachdev explains that through the visual depiction of the sacred texts, plants emerged in art and design. Similarly, the Mughals, with their penchant for gardens, brought schematic representations of flowers into the iconic Islamic geometric design.

The origins of botanical art as a genre lie in scientific documentation — plants were studied for their medicinal and thereon economic value. In the 17th century, the French colonists were among the first to commission Indian artists in the unpublished manuscript Jardin Lorixa (Garden of Orissa). The British though, were instrumental in charting the region’s natural history. To this end, local artists, the genre’s unsung heroes, worked with surgeon-botanists and scholars in the field. The resultant ‘Company botanicals’ is a sub-genre of the style of painting known as Company School or Kampani Kalam. It’s a style that points to the hybrid, Indo-European painting traditions, developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, by Indian artists under the patronage of the East India Company. The artworks are marked by miniature painting techniques, albeit with a European influence. The period also witnessed a shift in medium from gouache to watercolour on European paper.

With her ongoing doctoral work, which explores pedagogical approaches for the study of plants through art and design, Sachdev hopes to formally extend the scope of botanical art beyond its scientific origins. By doing so, she believes we’d be actively engaging today’s student (tomorrow’s designer) with botanicals in their immediate surrounding — through everyday designs like rangoli and truck art, architectural motifs and living-breathing plants themselves.

From an aesthetic point, designer Vidhi Khandelwal, founder of lifestyle e-shop The Ink Bucket, credits botanical art’s popularity to the calming effect of nature. “It’s easy on the eye and can instantly add charm to any space,” she says. Its evergreen style, a definite bonus, offers flexibility across mediums. This is evident in its increasing popularity among contemporary lifestyle brands. Design label Nicobar’s recent Vipasa home collection celebrates the free-spirited gypsy with a tangle of flora. Wallpaper company Nilaya by Asian Paints’ Fiji Garden line is classic with its vintage botanicals. And baby lifestyle brand Masilo’s Tropical Vibes Only is a dreamy cot bedding set with leafy, watercolour renderings.

The art and design fraternity agrees that the resurgence of botanical art is a reflection of our current relationship with the natural world. Could the trend be a two-dimensional offshoot of the larger biophilic design movement? A way for those without the luxury of time or space to connect with the subject at hand, perhaps? While partially agreeing, Gupta asserts that for many, herself included, it is like oxygen. And the need to wear your passion on your sleeve (or walls) is why we’re seeing the nature theme far more integrated today.

The way lifestyle labels like Forest Essentials and Fabindia employ botanical illustrations also subtly drives home their eco-positive messaging. Khandelwal talks about her work with Indian bistro chain Fabcafe by Fabindia. Her series of signature murals and wallpapers echoes the brand’s credo of clean, healthy eating.

Finally, botanical art and design is a gentle reminder of an otherwise harsh reality: our current environmental crisis. “People across the board are feeling a profound disconnect from nature, and perhaps botanical art is an accessible inroad by which we seek to re-establish that connection,” says Nirupa Rao, a Bengaluru-based, self-taught botanical illustrator. Best known for her work on the book Pillars of Life — Magnificent Trees of the Western Ghats, Rao believes “art can serve to humanise a subject like plants, which we currently seem to be rather blind to.”

That design has the power to alleviate plant blindness may seem like a given. The bigger question though, as Sachdev says, is about the quality of awareness cultivated. We, for one, are hoping that nature will take its course.

Gretchen Ferrao Walker is an editorial consultant who has collaborated with Indian and international publications like GQ India, Forbes India, Time Out, Architectural Digest India, Design Anthology and Collectively.org. She is the former editor of travel bimonthly Time Out Explorer and current mum to a 2-year-old. She enjoys embroidering and making pictures.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.