My mother often says that she is solar-powered, which succinctly explains the relationship most of us have with the sun. Sunlight is integral to our existence — it signals the change of seasons, the dawn of a new day, safety in public spaces, warmth in colder climes, and kickstarts life-giving processes like photosynthesis in plants and Vitamin D formation in humans. While sunlight is not in short supply, it has become a precious commodity in urban spaces such as Mumbai, a city surrounded by water on three sides, that has one of the highest densities of population in the world.

This year, amid the pandemic and while adhering to strict lockdown measures, I’ve been thinking about our daily access to sunlight — more so for those living on lower floors and in congested spaces — and how it has become glaringly limited in this city of high rises.

Over decades, as the city has welcomed rapid economic growth and a constant influx of migrants, its urban planning priorities have been skewed toward accommodating this burgeoning population. In the process, providing sufficient access to sunlight and air has become a privilege not afforded to all.

In the 1970s and ’80s, renowned architect Charles Correa, whose practice factored in climate and local building styles, demonstrated how open spaces could be designed into homes for high densities of population with his Incremental Housing project in Belapur, Navi Mumbai. But those designs don’t seem to have travelled across the Vashi Bridge.

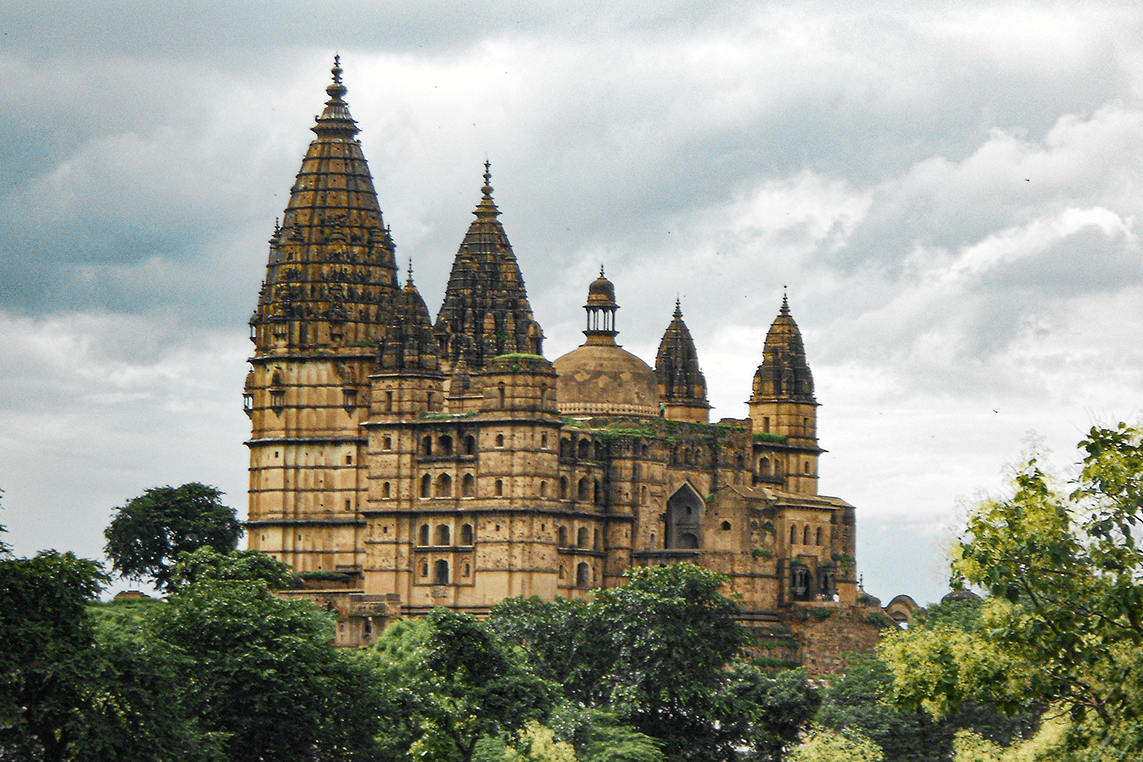

Sunlight has always been a concern — even in the architecture of ancient civilisations, the sun played an integral role. The concept of sun-centric architecture can be seen as far back as the Indus Valley civilisation of Mohenjo-Daro, around 2500 BCE, where houses had courtyards, streets were laid out in a north-south grid that optimised the amount of sunlight coming in, and walls were thick and high to regulate the sunlight and heat. Then there’s the first noted dispute over access to sunlight, which took place in second-century CE Greece. What is fascinating is that this dispute, which was contested in the court of Ulpian, was attributed to the sudden increase of population, structures and other elements that cast shadows on the sun rooms called ‘heliocaminus’ — not very different to the factors responsible for blocking sunlight in recent times.

Today, countries around the world have varied legislations that govern access to sunlight. In India, it is The Indian Easements Act of 1882 that covers the right to light, which if exerted, could restrict those who inhabit adjoining properties from developing their property if it could potentially obstruct light on the other property. The catch? That the property asserting its right to light should have received uninterrupted light for twenty years prior.

The proposed Mumbai Development Plan 2034 puts forth a further increase in FSI (Floor Space Index) for residential and commercial properties in the city, allowing for a higher ratio of built-up area on a plot of land, and consequently setting the stage for even more cramped quarters for the city’s residents in the years to come.

How do we address our basic right to light in a city that is constantly growing? Would more pockets of green between our buildings allow light to permeate this concrete jungle? Should we treat the pandemic as a one-off occurrence and continue developing our urban spaces as usual or do we provision for regular access to light in a post-pandemic world?

In the meantime, for an hour and a half each day while we’re staying cautious and indoors, I’ll continue following the sun around our home.

Where is the Sun?

As the year progresses, the sun appears to do a gradual dance across our spaces, lighting up different areas during different seasons. If you track it closely, the light tends to oscillate between two specific points, retracing its steps after a while. If mapped by noting the position of the sun in the sky at the same time from the same location, it will form a figure-eight path (called analemma by astronomers) over the course of the year. While the sun rises in the east and sets in the west every day, Earth’s elliptical path around the sun as well as its angle of tilt along its axis are what cause this gradual shift in movement in the sun’s overhead path.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.