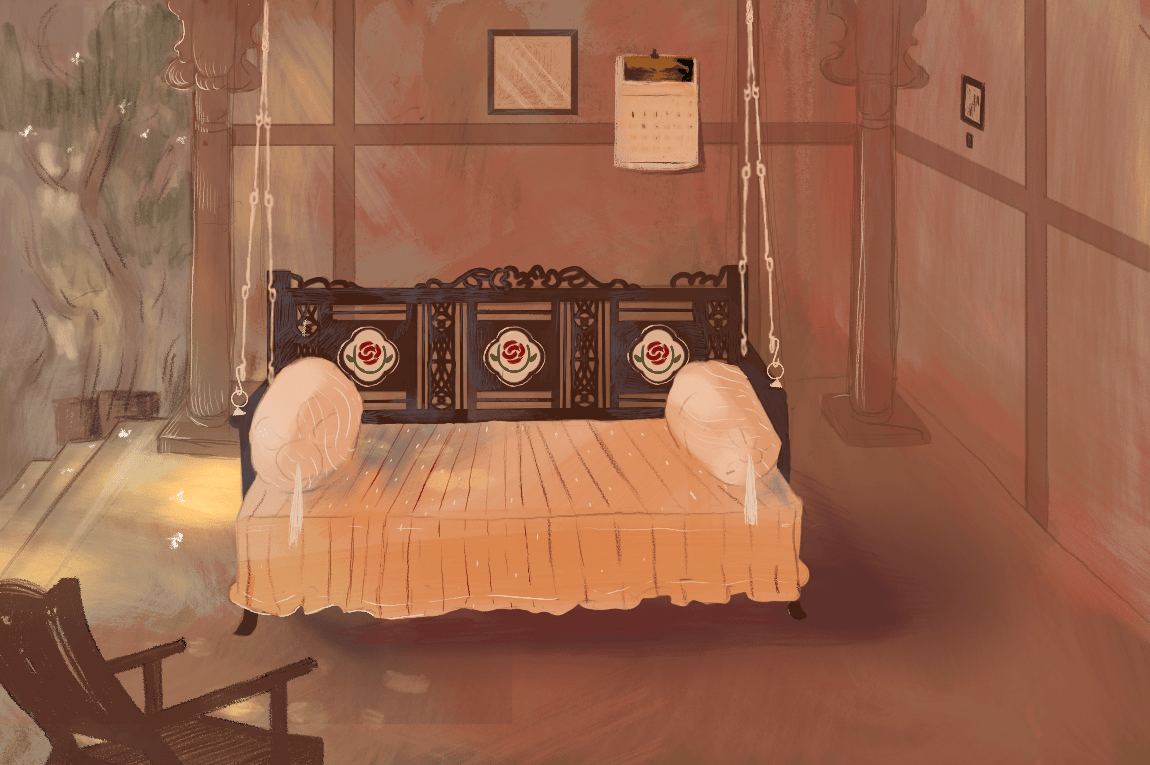

Bombay is a city conjured up “from marshes, salt flats, isolated islands, open sea, seemingly from the air itself,” as Gillian Tindall writes in City of Gold. The South Bombay peninsula we know today was a reclamation experiment that concluded in 1845, in which the East India Company built what they thought was a city submerged in the sea between the original seven islands. With this new landmass came a long stretch of waterfronts snaking along its Western perimeter. It is impossible to imagine living here without these frontiers between us and the ocean. What would Bombay be without the sensuous curve of Marine Drive or the jagged yet friendly Carter Road promenade? Where would its citizens go in times of love, leisure, play, World Cup win–jubilation, and the kind of melancholy that only gazing at the horizon can fix?

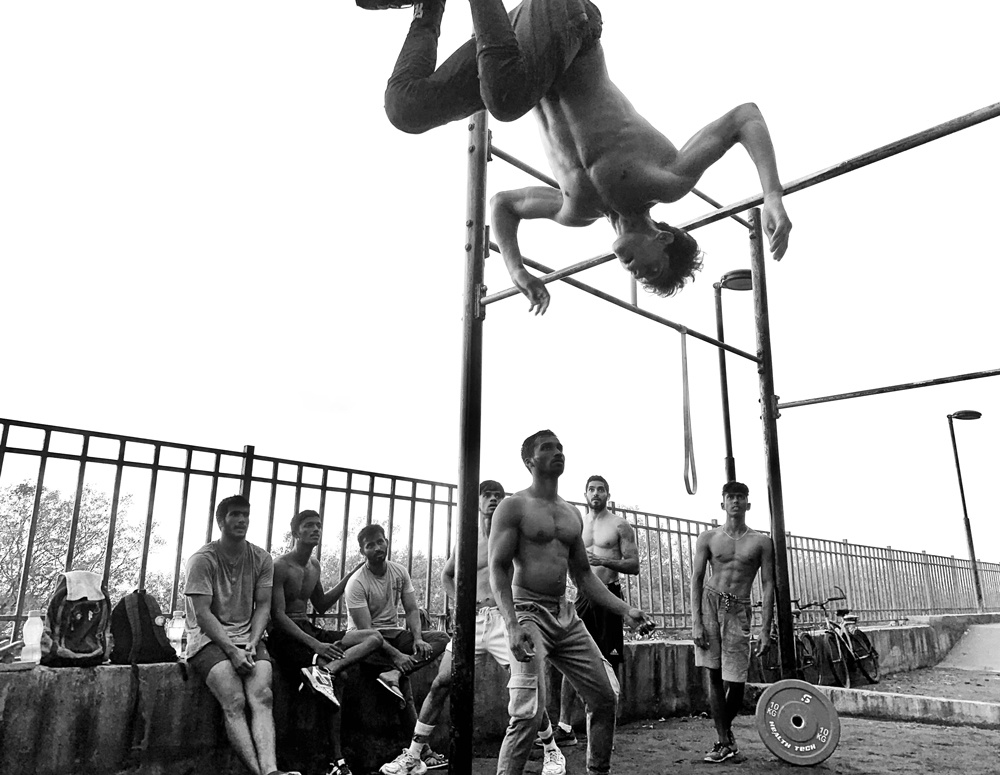

All my life, I’ve lived three minutes from the 85-year-old Worli Sea Face promenade. From my front door, I just need to take 100 steps forward and then 150 steps right and I will reach the ocean. Only two steps separate its slim path from the traffic-clogged road, and a short wall stands between it and the moody, grey Arabian Sea. Its concrete surface is littered with the Mumbai public space–bare minimum: rickety benches, outdoor gyms, battered date palm trees, an unofficial kabootar khana. It hugs the coast for about two kilometres before ending at the steady discharge of cars coming off the Bandra-Worli Sea Link. Right after it is Worli Koliwada, the over 800-year-old fishing village that is home to the Kolis, who were among the city’s first inhabitants, and an Indian Naval base. Although it is unexceptionally designed, Sea Face acts as a gym, a playground, a romantic date spot, a kitty party venue, an exhibition centre, a Physical Training class for Greenlawns school, and a dog park, amongst other things, and usually all at once. The promenade is the heart of the community and the closest thing the neighbourhood has to a free public space surrounded by nature. It is a rare open path in a city where nearly nothing else is designed for walking. But this treasure, along with many others along the city’s waterfront, is rapidly disappearing.

As someone who grew up without a “building compound,” Sea Face was my playground, and I shared it with thousands of other people, who presumably didn’t have compounds either. Mumbaikars have only about 1.24 square metres of accessible open space per person, amongst the lowest in the world. In comparison, a typical car parking space measures about 12 square metres. In our record-breakingly dense city, anyone can find the space and fresh air they deserve by the water, no matter where they live and how much money they have. But during the pandemic lockdowns of the past year when most beaches, gardens and promenades were closed to limit the spread of the virus, people who didn’t have compounds and private gardens were forced to remain indoors indefinitely. Anca Florescu Abraham, co-founder of Love Your Parks Mumbai (LYPMumbai), believes that local civic bodies need to trust citizens to safely use the spaces they sorely need.

“The easiest way to bring down the numbers from their [the civic bodies’] point of view is to shut down the city and keep everyone at home,” she said. “But the trickier route would be to keep things open with proper safety measures in place and to devise solutions that don’t imprison everyone, especially children and the elderly from low income backgrounds who are left to struggle in limited space.”

LYPMumbai harnesses the power of local communities to stand up to the often opaque bureaucratic functioning of the many civic bodies in charge of the city. It’s a technique that has worked for people across the world, even in this city; it was a citizen’s movement which saved Bandra Bandstand and Land’s End from privatisation in the late 1990s. But to fight for a place, we must intimately know it. It’s hard to do in Mumbai, where only a third of the 149km coastline is open to people.

At Worli Sea Face, people have been involved, and with a passion. As a child, I used to look forward to receiving the Worli Walkers’ Association’s newsletter Worli Waves for its updates about the promenade. The 140-odd benches on Sea Face are deeply connected to the neighbourhood: they were each donated by a resident in memory of a loved one and engraved with wonderfully quirky messages like “Watch the waves a wee bit” and “Smile; Let Go.” Recently the BMC painted over the benches in a violent shade of robin’s egg blue.

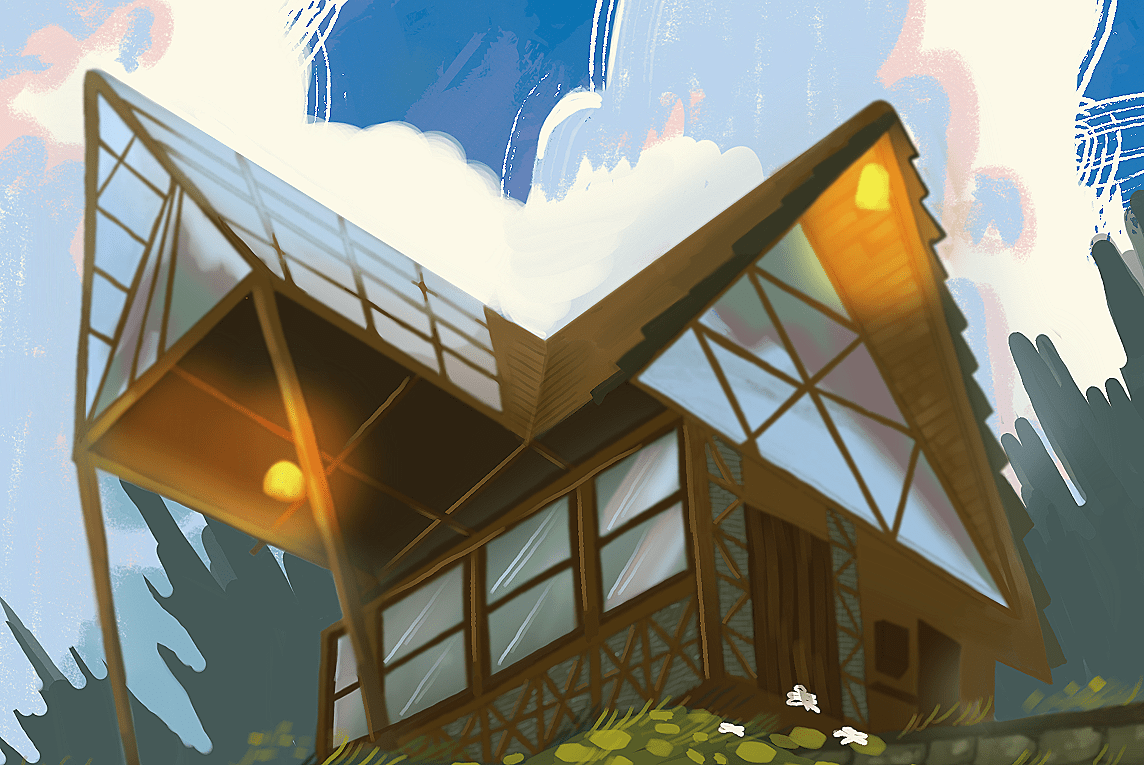

But even when a place enjoys this level of intimate attachment it is not safe from reckless re-development. It’s impossible to talk about our coastal city without mentioning the Coastal Road, a 29.2-km freeway being built along the city’s western shore, which is going to dramatically change our relationship with the sea. My beloved Sea Face promenade has been almost completely demolished to make way for the megaproject, and instead of the crashing waves, visitors can now look upon a wall of bright yellow barricades with images of the massive looping roads that will soon rise up from the sea. The new plans promise a 4km-long and 20m-wide promenade, 700 metres away, to replace Sea Face. But while Sea Face has no barriers and even has wheelchair ramps, not enough is known about the design of the new promenade, as the artist’s renderings released by the civic bodies are vague and subject to change.

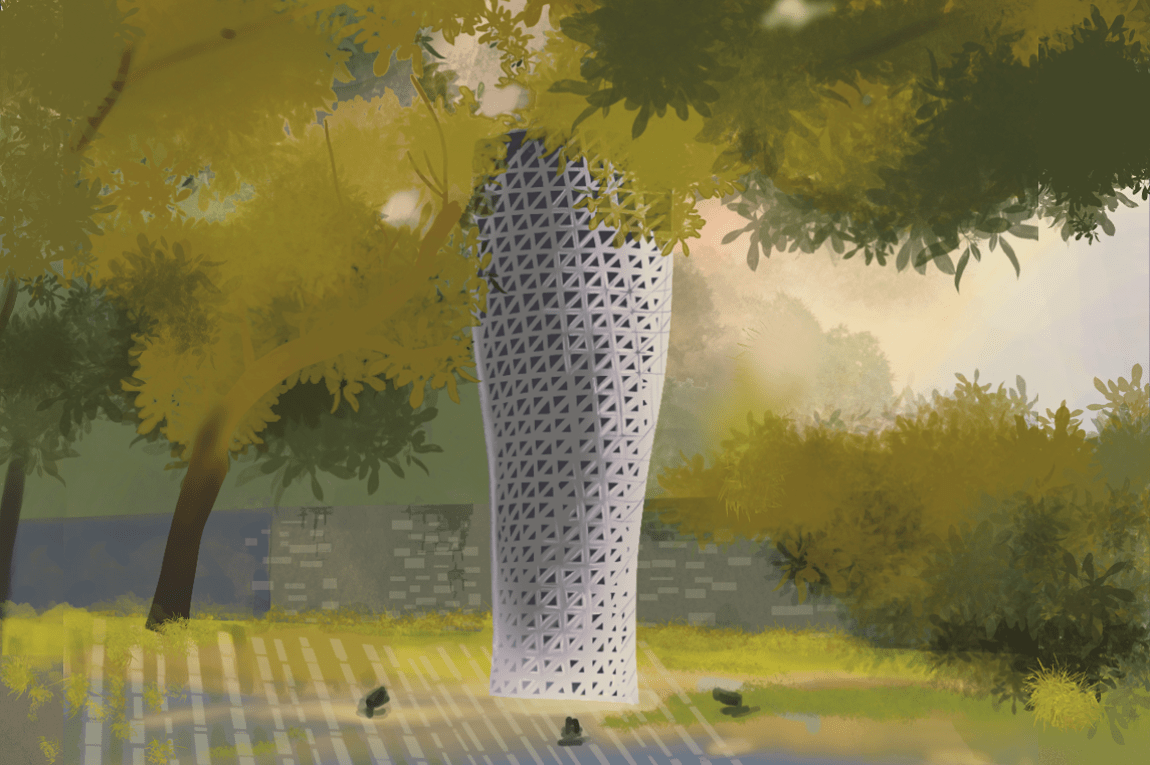

Environmentalists and architects have also been crying themselves hoarse about the Coastal Road’s many flaws. Amongst other things: it serves only the tiny minority of car owners; it will destroy mangroves and increases the city’s vulnerability in the face of storms and flooding; it could be simpler, cheaper, and less invasive, according to proposals by Abraham John Architects’ urban design and research platform Bombay Greenway and research by the architect and historian Robert Stephens. It seems we are doomed to be locked in a battle of one-upmanship with the Arabian Sea.

“Given its colonial origins, Bombay has an idea of mastery over nature that’s been etched into its DNA,” said Aaran Patel, a Masters of Public Policy candidate at Harvard Kennedy School of Government and a Bombay-native who has been chronicling the environmental impact of the Coastal Road since its inception. “But each monsoon, we’re seeing the shaky foundations of this logic. We need to conserve, expand and embrace our natural assets rather than seeking to conquer them.”

The history of Mumbai — “great city, terrible place” as the architect Charles Correa called it — is the story of a city being constantly destroyed and rebuilt. Its citizens, like those of many other great cities, feel a permanent sense of loss when they turn a corner and the building they expected is now rubble, or when cranes and cement dust clutter the otherwise open horizon. But there might be a productive way to channel the grief that comes with this ephemerality.

“I think realising the threat of loss is also an opportunity for discovery,” said Patel. “There are a few movements, like Marine Life of Mumbai [a collective which raises awareness about the city’s coastal biodiversity], which give me hope for the long run. They are a reminder to stop, pay attention and find new ways of seeing the city.”

It is inevitable that our seafronts will be transformed over and over, but I don’t believe that they will ever cease to be “the great community spaces of our city,” per Correa. I can only hope that the future designers of Worli Sea Face remember the golden rule of design: empathy; for the emotional lives of its users, like the Kolis, who inhabited Worli long before there were cars, and for those who love the promenade as if it is an extension of their homes. When the directors of the East India Company ordered its officers to “Redeem those drowned lands of Bombay” in 1684, a new city was built. If our elected officials have the power to conjure land, we should demand that they do it to make free space for our simplest needs: walking, playing, and watching a brilliantly hued Bombay sunset.

Sneha Mehta is a writer and designer. She writes about the cultural implications of design and food, and how the objects we surround ourselves with shape our identities. You can find her on Instagram @snemeh.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.