What are you currently reading? Is there a work of writing you frequently revisit?

I’m reading The Complete Taj Mahal by Ebba Koch, and I often return to City of Djinns by William Dalrymple. I also read a lot of Thich Nhat Hanh.

You’ve led the extensive restoration and redevelopment work of the Humayun’s Tomb Complex, Mirza Ghalib’s Tomb, Hazrat Nizamuddin Basti, and Sunder Nursery in Delhi for over a decade. What were the challenges you faced whilst working?

I have worked for the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) for two decades now. During this time, it has been a privilege to be responsible for some really visionary projects supported by His Highness the Aga Khan, such as the restoration of Bagh-e Babur in Kabul and of course the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative in Delhi.

Working on 60 or more monuments within the Humayun’s Tomb–Nizamuddin Basti area of Delhi, we have been able to demonstrate a model conservation approach for the Indian context — an approach centred on employing master craftsmen using centuries-old building traditions, materials and craft techniques. This has led to 12 monuments in the area being added to the World Heritage List and the Archaeological Survey of India revising their conservation policies to include an emphasis on craftsmanship. The AKTC’s conservation efforts in Delhi have also created 650,000 man-days of work for master craftsmen.

Do you see the practice of conservation going beyond reinstating architectural integrity? How can one attempt to make it more exhaustive and collaborative?

In India, conservation has been viewed as an elitist endeavour simply because conservation efforts have not led to improving the quality of life for local communities. The AKTC’s efforts in Nizamuddin aim to demonstrate how conservation and development need to go hand in hand. Here, we have coupled conservation efforts with major efforts towards socio-economic development, working with the local community to meet their needs. We have invested heavily in improving education and health infrastructure — over 250,000 individuals access the health facilities created here. We implemented vocational training opportunities that have helped almost 2000 youth get jobs. We built toilets long before it was sexy to build toilets in India, and carried out urban improvements such as landscaping neighbourhood parks and streets. I am very encouraged with the interest in the project that has led to the government initiating schemes to encourage similar efforts elsewhere.

Were there any early influences that made you foray into conservation architecture?

Looking at the modern architecture in Delhi, did I even have a choice? As an architecture student, I realised that historic buildings were built with so much attention to detail which is clearly missing in today’s fast-paced world. I also realised that Delhi’s heritage was at serious risk. I have been fortunate enough to have a chance to work in a field that has given my life much meaning.

What is it like when a building reveals itself to you? How do you identify signs of distress and disrepair before intervening?

I have often said that a conservation architect is like a doctor for historic buildings. So indeed, one has to understand the structure, its uniqueness, its significance and the intention of the original builder. Accordingly, the conservation effort can range from preservation to reconstruction and often includes an array of interventions. Thorough documentation, condition assessment, and archival research help, and so does having an inter-disciplinary team, as we do at the AKTC.

How important is it to integrate conservation practice with urban design as well as intangible living heritage?

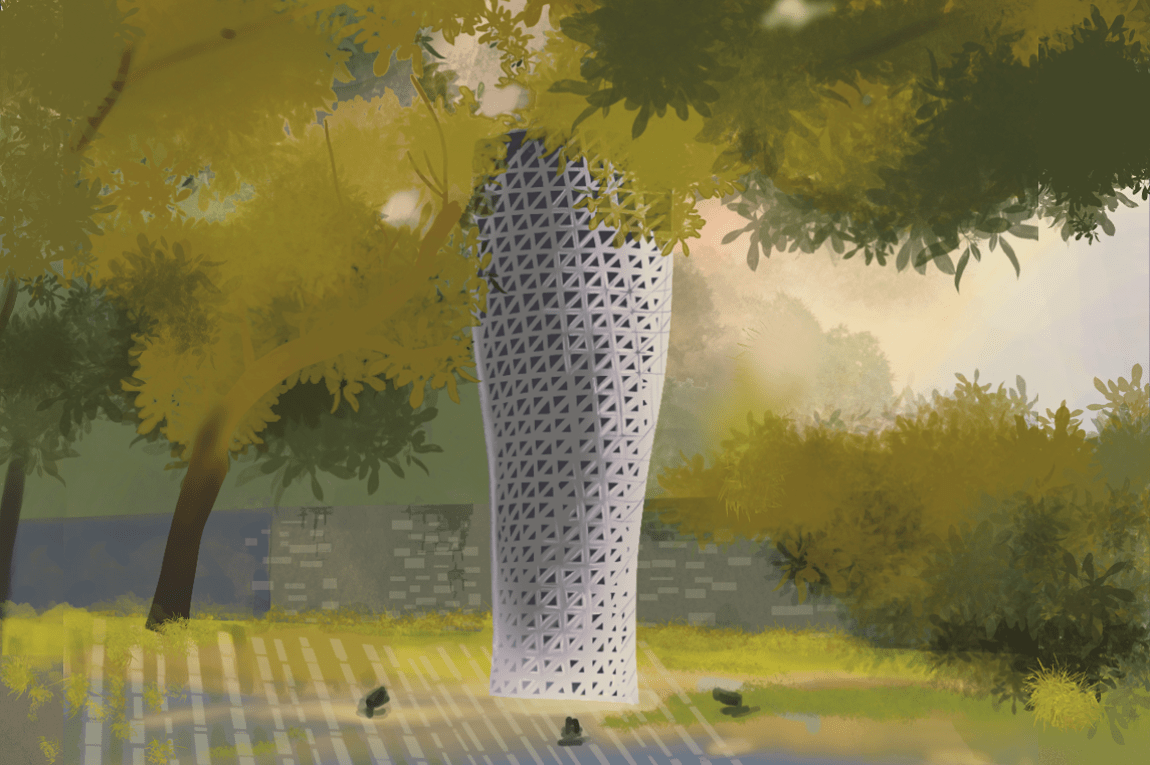

In 2015, India signed on UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape resolution. This resolution urges member states to consider the urban context of the heritage sites to be as significant as the monument itself. The resolution is itself based on the model projects the Aga Khan Historic Cities programme has carried out worldwide — in Cairo, Mali, Zanzibar and Kabul, amongst other historic cities — since the 1970s.

In Nizamuddin, the conservation and socio-economic efforts have been coupled with major landscape and urban design interventions as well as urban planning efforts such as writing out the heritage by-laws for the National Monuments Authority.

The creation of Delhi’s heritage park — Sunder Nursery — has been part of this effort and a huge endorsement. Within weeks of the opening at Sunder Nursery last year, it was ranked amongst the world’s 100 greatest places by TIME magazine. Again, the AKTC’s efforts in Nizamuddin have allowed us to work on the cultural legacy of icons such as Hazrat Amir Khusrau and Rahim, leading to publications, seminars, festivals and concerts.

When preservation of a structure is undertaken in the garb of restoration, do you think a certain sensitivity, or even pride or respect for it is lost?

Restoration is as much part of the conservation effort as is preservation. Specially so when inappropriate past interventions have used inappropriate modern materials such as cement which need to be removed and replaced to safeguard the future of the building. However, restoration can never be carried out without evidence of what existed and without recourse to require craft skills. If done well, restoration leads to pride and respect for the heritage asset.

In India, many of our sites are crying out for restoration carried out by master craftsmen, not petty contractors. The grandeur of our past has been obliterated at far too many sites.

You travel extensively for work. What learnings have you gleaned from your travels?

In India, we treat our heritage as a burden; the world over, countries and communities have demonstrated how conservation can help meet several objectives of the government — increased and sustainable tourism, revenue generation, creating more jobs, instil a sense of pride and well-being and even communal harmony through the understanding of varied cultures and beliefs.

Do you have a favourite monument or building?

Ha! Many favourites — it’s been a joy to be working particularly at Humayun’s Tomb and the Qutb Shahi tombs in Hyderabad.