This story is part of How About Now: Going Electric, an independent, carbon-neutral magazine produced by The Paper Planes Agency for WorthWhile Future Foundation, a non-profit at the intersection of finance and sustainability. The magazine was published in June 2023. Read more about How About Now here.

It’s hard to believe we’re living in an age where the end of vehicles with internal combustion engines may be nigh. Governments are no longer entirely dismissing the science, even as they sweep land and sea for new sources, markets and loopholes for oil, gas and biofuels.

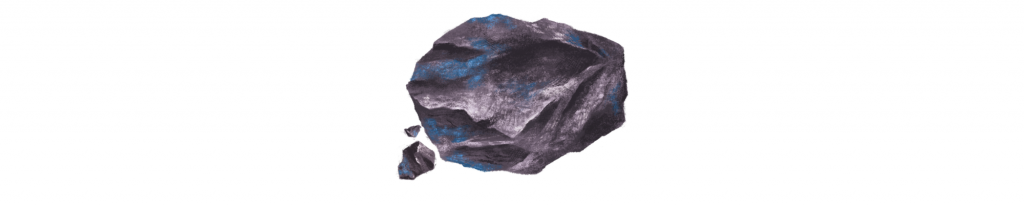

Lithium, cobalt, graphite, manganese, nickel, zinc and rare earth elements are the new metals and minerals on the block, needed in large quantities to power the renewable, electric future for the world to have a chance in hell at keeping warming under 2°C.

While lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite are essential to making batteries for EVs, rare earths are critical to the magnets used in the motors that make EVs run, besides the wind turbines. Also critical to the transition are copper and aluminium that are indispensable for all electricity-related technologies.

The transition has set in motion a global mining boom, as countries like the US scramble to shore up supplies and protect domestic industry. But what shape will this transition take, especially in low-income countries in the Global South that have a history of resource extraction by Northern countries, and are the most impacted by climate change? These are countries that have vulnerable communities, poor or plentiful access to mineral resources, and need financial and institutional support to meet sustainable development goals.

On 9 February 2023, the Indian government announced the discovery of a substantial 5.9 million tonne reserve of lithium in Jammu and Kashmir’s Reasi district. The announcement was cheered by many: India imports nearly all of this climate-critical mineral to feed its nascent and troubled EV industry. A lithium reserve this size by itself vastly exceeds the deposits identified by other countries that are already ahead in the critical energy race. India has already announced that it plans to put this reserve on the auction block by June.

But after the initial jubilation comes concern that the Indian government is putting its cart before the self-driving Teslas. For one, researchers have still not fully assessed just how much of this deposit is minable, what quality it might be and what it will take to extract it. Then there’s the longer shadow: of what the discovery means for people living in one of the most militarised regions on the planet, whose voices are often shut down for the ‘greater good’.

“People salivating at the lithium discovery in Jammu seem to conveniently ignore that the last assembly elections in J&K were held in 2014,” tweeted atmospheric scientist Shazad Gani. “Where are the just (adjective) energy transition people?”

The question is an important one, and one for India to consider as it embarks on its journey to net zero.

The term ‘just transition’ has its origins in the North American labour and trade union movement. The International Labour Organisation defines it as “greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities and leaving no one behind”.

Just transition is a leitmotif in climate conversations in this critical decade, when it is evident that decarbonising rapidly is essential, but the term underlines that it must be fair, inclusive and equitable. The latter is even more pertinent, given expectations from rich countries that the developing world must cut its appetite for coal, gas and oil at a rate unseen in history, while former colonial powers who’ve had all the fossil fuel advantage, resources, technology and lead time drag their feet

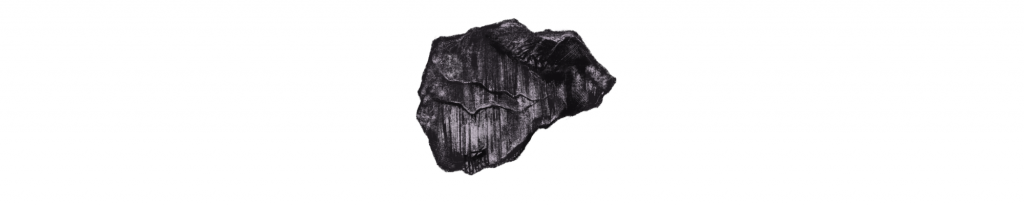

Such a transition also comes from a recognition that workers still have their present and future tied to fossil economies. Millions of Indians rely on coal for their livelihoods, and weaning away from a fuel that guarantees jobs, albeit arduous and hard to come by, will hit parts of the country where coal has come to dominate all other productive economies.

I spent my twenties staring into some of India’s biggest coal mines that swallow huge amounts of land to yield the energy vital to India’s development, but don’t guarantee the same power to the indigenous and local communities that live around them. In nearly every single coal block I visited, communities were shut out of consultations, their consent to divert climate-critical forests never sought, and the impacts of pollution that coats their lives, never explained and barely mitigated.

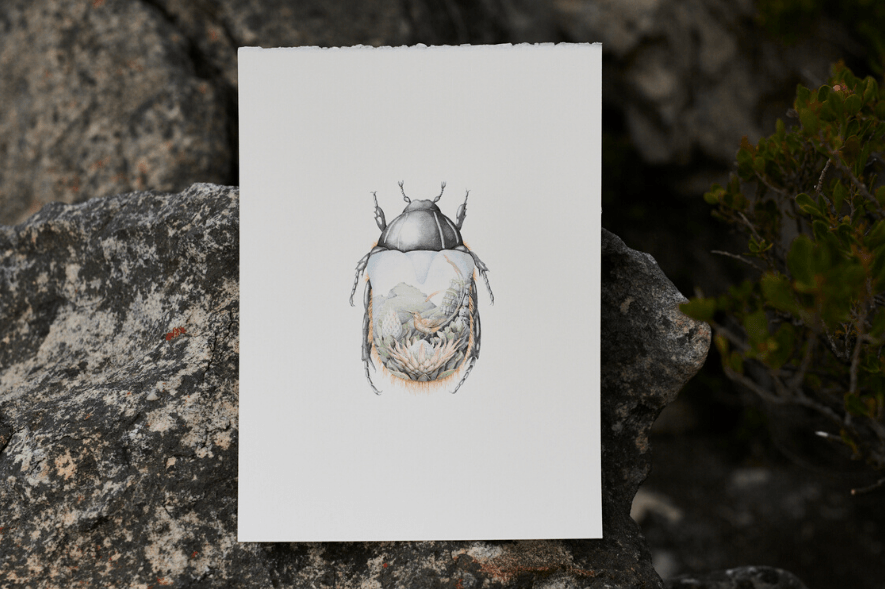

What the energy transition, in all its progressive tech-futurism, has not yet fully embraced in practice is an ethical, rights-based mandate on how we mine for the minerals of the future, still based on an extractive paradigm of the past.

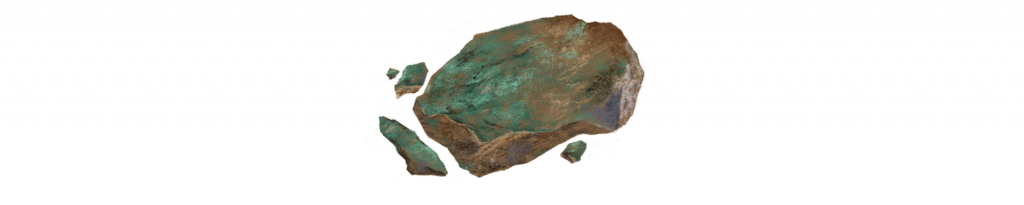

Because let’s face it: There’s no such thing as a beautiful mine. Extracting the metals and minerals that will serve the world’s low-carbon transition is by no means inherently greener than fossil fuels and traditional industry: Acquire land, strip it of all things living, blast, cut, crush, refine, smelt and repeat. The processes might differ — for instance, in the ‘lithium triangle’ of Bolivia, Argentina and Chile, mining is not the extraction of rock, but water from its shimmering salt flats, which has sparked protests and legal action from indigenous and local communities over water shortage fears, and deja vu of outsiders profiting off their mineral resources, which ruined the continent. On April 20, in a move to protect its resources, Chile’s president Gabriel Boric announced that he would nationalise the country’s lithium industry, following the lead set by Mexico last year. The global low-carbon transition is not as ‘clean’ or ‘green’ as we’d wish it to be.

But the world mines far more coal today than it does transition metals. That said, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA), EVs and battery storage will account for about half of the mineral demand growth from clean energy technologies by 2040, if we are to achieve the goal of net-zero emissions worldwide by 2050. To even get to the goals of the Paris Agreement — i.e. limiting global temperature increase to well below 2ºC — would mean four times the mineral demand for ‘clean’ energy by 2040, while hitting net zero globally by 2050 would imply that by 2040, we’d need to mine for six times the minerals being extracted today.

Demand for lithium, cobalt, nickel and copper is already soaring. According to supply chain intelligence platform Benchmark Source, at least 384 mines would need to be sunk to meet the world’s EV and battery storage demand by 2035.

But, according to environmental sustainability researcher Hannah Ritchie, even at this peak scenario in 2040, and even including aluminium extraction, the demand for these critical minerals would be in millions of tonnes (43 million tonnes), unlike the 15 billion tonnes of coal, oil and gas we extract each year.

Importantly, the low-carbon transition upends the world’s energy map, given the distribution and concentration of these critical minerals in particular geographies. For instance, in 2019, the Democratic Republic of Congo accounted for 70% of the world’s cobalt production, China for 60% of the world’s rare earth elements, and Australia, over half of the world’s lithium production. Chile has both copper and lithium, while Indonesia accounted for a third of the world’s nickel. Interestingly, much of the processing of these minerals takes place in China.

This distribution poses a new challenge to nations that, post-COVID and the start of the war in Ukraine, have been focused heavily on energy security, accelerating renewable energy deployment, reducing expensive fossil fuel imports and protecting their domestic industry from supply chain shocks.

We’re now in the middle of ‘green trade wars’ where countries — in particular, the US and in the EU — are racing to secure their own technologies of the future to compete with China, but minerals could prove to be that stumbling block. India, for example, relies heavily on imports for many of its EV manufacturing and renewable energy needs. While the latest national Economic Survey points to resources of nickel, cobalt, molybdenum and heavy rare earths, just how big these resources are is anybody’s guess, as is the Jammu lithium discovery.

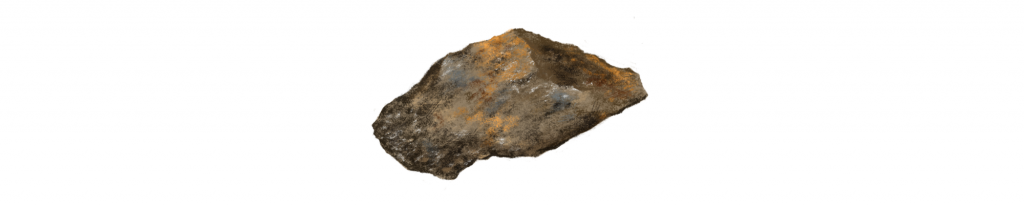

India currently imports almost all of its nickel ore, for instance. Interestingly, the country’s mining authorities estimate that the steep waste dumps in Odisha’s chromite belt could be a significant source of nickeliferous limonite and cobalt.

While India holds 18% of the world’s chromite reserves, in 2019, it was the world’s third-largest producer of the metal that makes ‘stainless steel’ stainless. In 2011, academics at Odisha’s Siksha ‘O’ Anusadhan university estimated that nearly 70 million tonnes of spent earth, or overburden, had been stockpiled by chromite mining in the Sukinda Valley, which has the misfortune of holding 98% of India’s chromite reserves. In 2007, Sukinda was ranked as the fourth-most polluted place on earth by the Blacksmith Institute. Hexavalent chromium, produced from the mining, refining and smelting of chromite, is deeply carcinogenic and is best known as the silent villain in the film Erin Brockovich.

Nickel also occurs along with uranium in Jharkhand’s Jadugoda, where Ho adivasis have died from the effects of radiation and poor waste handling.

The Geological Survey of India has also begun exploring the deep sea around Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar islands for nickel.

In April, countries sparred in Jamaica over opening the deep sea as a new frontier for mining, but failed to finalise any standards, leaving a backdoor open for mining companies. While some eye the ocean as less complicated for extracting base metals for batteries, countries and scientists are calling for a precautionary pause and an outright ban on deep-sea mining, given how little we understand of potential impacts on ocean health, already under threat from climate change.

What, then, are the ways to potentially reduce these impacts?

Amnesty International — which investigated how batteries used by EV auto giants could be linked to child labour in the Democratic Republic of Congo — lays out a set of principles for the battery industry and governments. These range from encouraging businesses to “pursue resource-efficient design, repair, and reuse” to engaging with human rights defenders and responding to their concerns instead of shutting them down. It asks companies to “refuse minerals from the seabed”.

Meanwhile, researchers from the Climate and Community Project, a climate policy think tank, examined ways that the US’ booming EV industry could extract less lithium, based on case studies of impacts in Argentina, Chile, the US and Portugal. They found that the US, where New York and California have already banned the sale of petroleum cars by 2035, can shift to zero-emissions transport while limiting its lithium mining footprint by “reducing the car dependence of the transportation system, decreasing the size of electric vehicle batteries, and maximising lithium recycling.” But that isn’t all: Prioritising and spending on public and active transit could also ensure an equitable transition that protects ecosystems, respects indigenous rights, and “meet[s] the demands of global justice,” they write.

India could choose a similar path instead of the highway-building, fossil fuel–subsidising spree that prioritises cars and sacrifices pedestrians and public health. Replacing cars with more cars is not the one climate solution for a country in which over 50% of all households own bicycles, but there aren’t enough bike lanes or EV buses to speak of.

Will India choose to transition to a more equitable form of resource use that it champions on a global stage? Or will it repeat the same violent extraction perpetuated in its coal, bauxite and mineral belts? Only time will tell but there is still hope from the ESG and investor community, which has only just begun to pay attention to violations that environmentalists have warned of for decades in the mining sector. It does not have to be like this. There is another way.

Get a copy of How About Now: Going Electric here.

Aruna Chandrasekhar is a climate journalist based in Mumbai. She writes about food, land and nature at Carbon Brief. She is on Instagram at @koylabear.

Joby is a freelance artist based in Kochi. She works primarily with digital illustration, 2D animation and comics. Find some of her work at @thejobay.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.