In all my years with my father, I never saw him step into the kitchen to make anything, not even a cup of tea. Of late, as I increasingly turn to cooking to anchor my days and steady my volatile moods, I spend more time in my kitchen and he’s always there giving me constant company. Under the cool black granite counter, in shelves hidden behind dark laminated doors, sit steel utensils of varying shapes and sizes, their form and design suited to a specific function. On their cool, grey smooth surface, through a series of fine dots, are engraved my grandfather’s and father’s initials. As I run my finger over the letters, they feel like nothing more than tiny scratches, but when time permits and nostalgia kicks in, I linger longer at the etchings that tell stories of days long gone by, of occasions that took place before I was born, and of course, of my family. Until a few years before my birth, my parents lived in a sprawling home with my grandparents, my paternal uncle and his family. Inside the common kitchen were utensils bearing initials of each of the patriarchs to establish ownership. It might not have been clairvoyance at play, but our family eventually did separate, and the engravings made the task of dividing the utensils a lot easier.

Years later, when I set up home with two friends in the leafy Cox Town neighbourhood of Bengaluru, my mother sent me a set of utensils and cutlery to help get my kitchen started. Amongst them were those that belonged to different generations of my family — most bought, many gifted and some that came free. The engravings they carried told me how they came into my mother’s kitchen and now, mine.

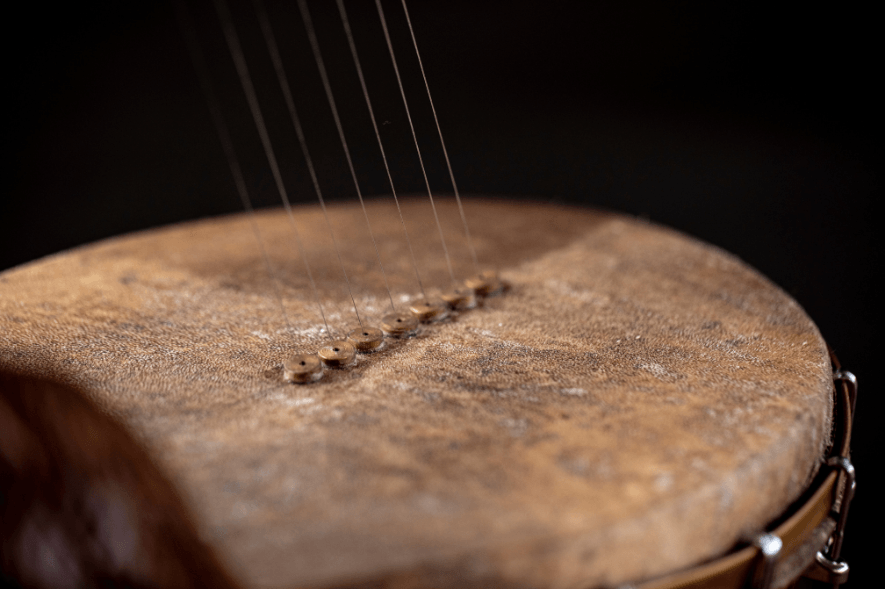

In Ahmedabad, Gujarat, the Vechaar Museum is a space that has over 4,500 utensils and vessels of varying materials, utility and design on display. The museum features vessels with engravings from all across the country. Years before steel became the metal of choice in kitchens, copper and brass vessels were commonly used, and it’s these copper and brass items that are found with engravings at the museum. I speak to designer Surendra Patel, one of the people instrumental in setting up the museum, to understand more about the history of engravings. “The practice of engraving possibly started to ensure that vessels do not get misplaced,” he explains. “When vessels were exchanged, the names engraved on them ensured that they went back to their rightful owner.” The oldest utensil with engraving that’s part of their collection is a 1000-year-old copper ghada (pot) from a village in Gujarat. It’s an engraving of the ancient Brahmi script and has not been deciphered, but Patel says it’s most likely the name of the family it belonged to.

While history isn’t certain about the origin of these engravings, my research led to conversations with several people who pointed to varied purposes of engraving utensils. For instance, engraving served as a way to keep potential thieves at bay. Tarot reader and astrologer Maheshwari Godse’s grandfather was the proprietor of Lakshmi Vilas, a restaurant in Tamil Nadu. When he passed, the restaurant shut down and all the vessels were distributed amongst his family members. Godse recalls seeing vessels in her mother’s kitchen engraved with a line in Tamil that read “Idhu Lakshmi Vilas hotelil irundhu thirudappathadhu”, which translates to “This was stolen from Lakshmi Vilas”. She says this was a common practice across Tamil Nadu to ensure patrons don’t make away with a vessel that caught their fancy.

Utility aside, art historian and anthropologist Jyontindra Jain, who set up Vechaar along with Patel, is of the opinion that back in the day, when only a few people could afford gold and silver, utensils and vessels were important possessions that reflected the wealth of a family. “When a girl was married, she was given a set of utensils as part of her dowry,” he says. “These were engraved with her family name or wedding details. The engravings proclaimed what the girl had brought with her.”

Engravings were often done to mark important occasions and auspicious events. In many parts of India, when a family member passes away, a vessel engraved with the name of the deceased person is distributed amongst family and friends. Sravanthi Challapalli, an independent writer who hails from Andhra Pradesh, recalls a moment when her grandfather was weighed down by all the loss surrounding him. She says, “One day, my grandad happened to notice that the steel glass he was drinking from was one such gift, engraved with the name of the dead person. He told my grandmother to throw out all those damn, depressing things. One can acquire quite a collection if one has an active social life.”

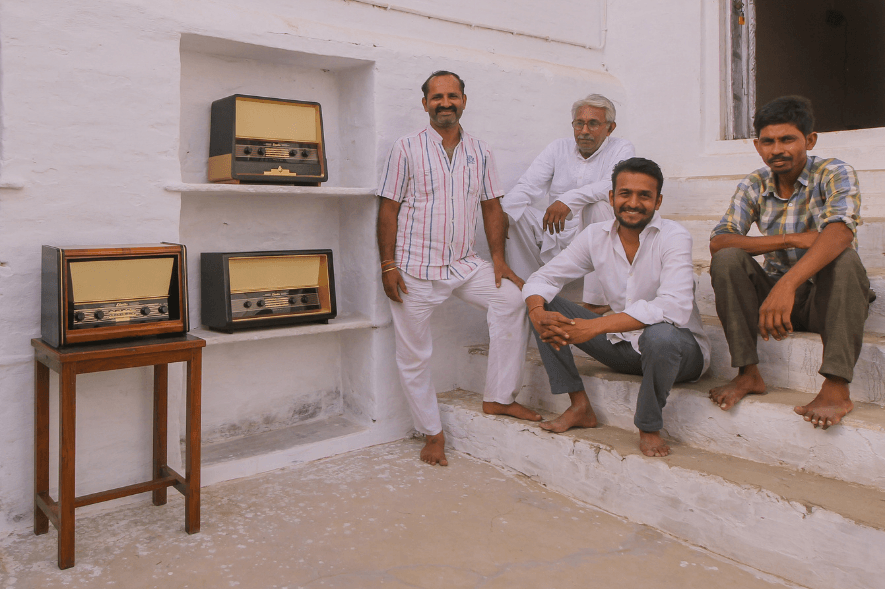

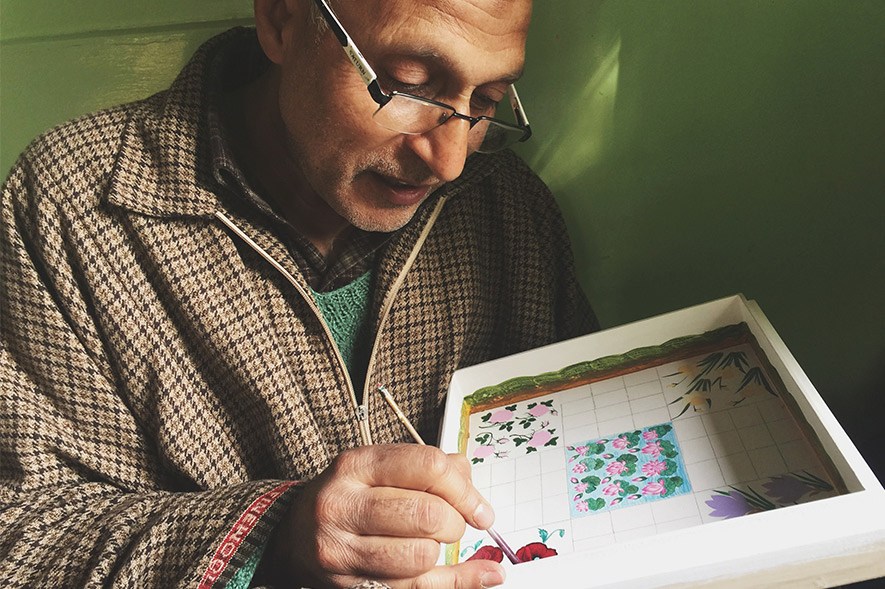

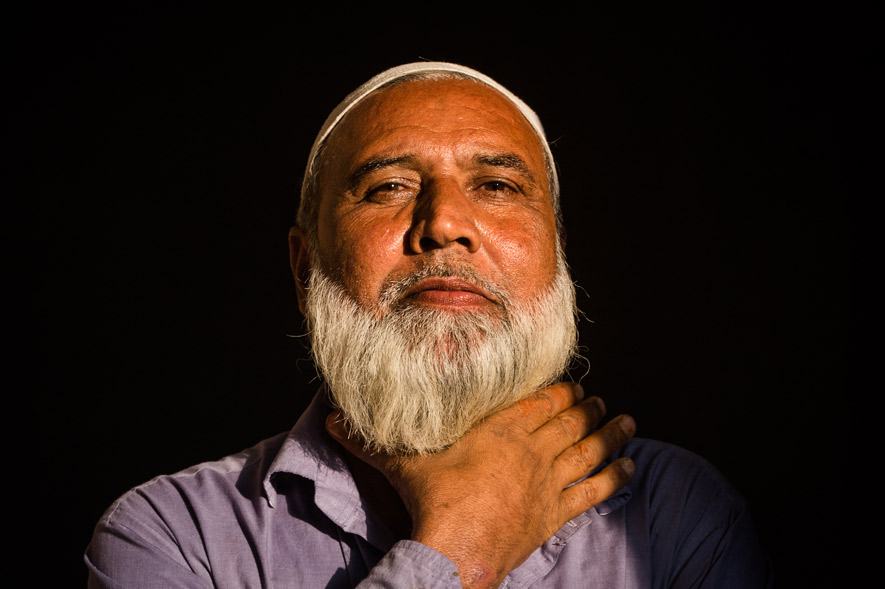

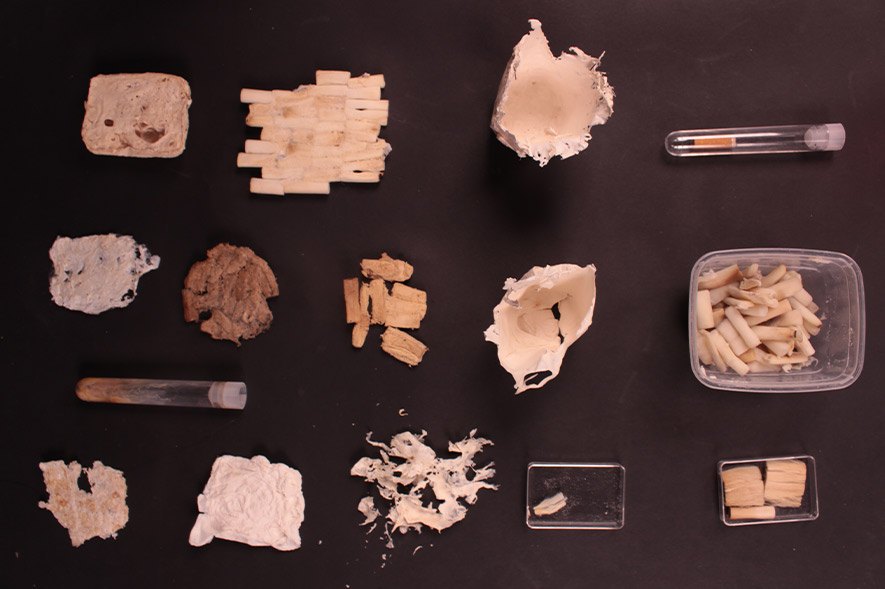

Photographs by Jaskiran Kapoor (left) and Chaitali Patel (right).

But far from stirring up grief, a set of four copper glasses and steel jug in media consultant and writer Jaskiran Kapoor’s kitchen acquired on her dad’s passing offer her solace. “In Punjab, when someone passes away, the Sikhs go to Gurdwara Patalpuri Sahib to immerse the ashes. There are rows of shops outside the gurdwara lined with steel, brass and copper utensils, with shopkeepers who engrave the names of the departed right there. We all got utensils of our choice. I picked two carved copper glasses and a steel jug, and got my father’s name engraved on them,” she recalls. “The real take back is the memory. I remember him each day as I use the jug for milk and glasses for water.”

With the passing of time and changing lifestyles, our kitchens have also seen many changes. Although glass, plastic and non-stick cookware occupy significant shelf space, there’s a resurgence in demand for traditional cookware that offer a variety of health benefits. Kaviya Maria Cherian, the founder of Green Heirloom, which retails this cookware made from clay, kansa, cast iron and other traditional materials, says that many customers ask for their utensils to be engraved. “Copper and bronze utensils cost a lot and customers want to ensure they become heirlooms that can be passed on. While most want names and years to be engraved, others ask for fancy designs,” she notes. Today, engraved vessels have become unintentional heirlooms, both treasured and cherished. The engraved object’s value is no longer defined by the cost of the material or labour involved in producing it, but rather by the heft of memories it carries. There’s a sense of comfort I experience every time I reach for that well-used steel tapeli in my kitchen. The neatly engraved and equally spaced initials of my father radiates warmth and feels like a tight hug on days when I desperately seek comfort.

Chaitali Patel is a freelance writer based in Dubai, and writes about travel, food and culture. She tweets at @07Chaitali.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.