Paper Planes is the official digital media partner for the third edition of Raw Collaborative.

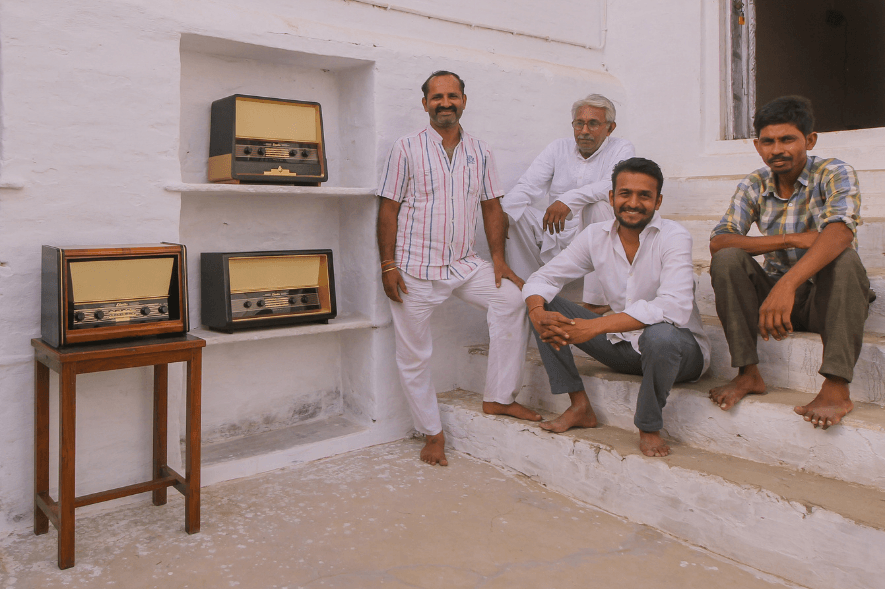

The makers of rich woven rugs, intricately carved wooden blocks, and sturdy earthen pots played a pivotal role at the third edition of Raw Collaborative, as part of the Craft Collective curated by textile designer Nehal Desai. The collective consisted of weavers, block makers, potters and painters from around Gujarat, some independent, others collaborating with design studios like Dehaati and Design Mill. Over the four days of the event, they exhibited their wares and conducted workshops where those attending got a chance to interact with the artisans and understand the processes behind the crafts. We spoke to the artisans about how they hone their skills, what the contemporary crafts scene is like, and why independence is imperative for their trades to thrive.

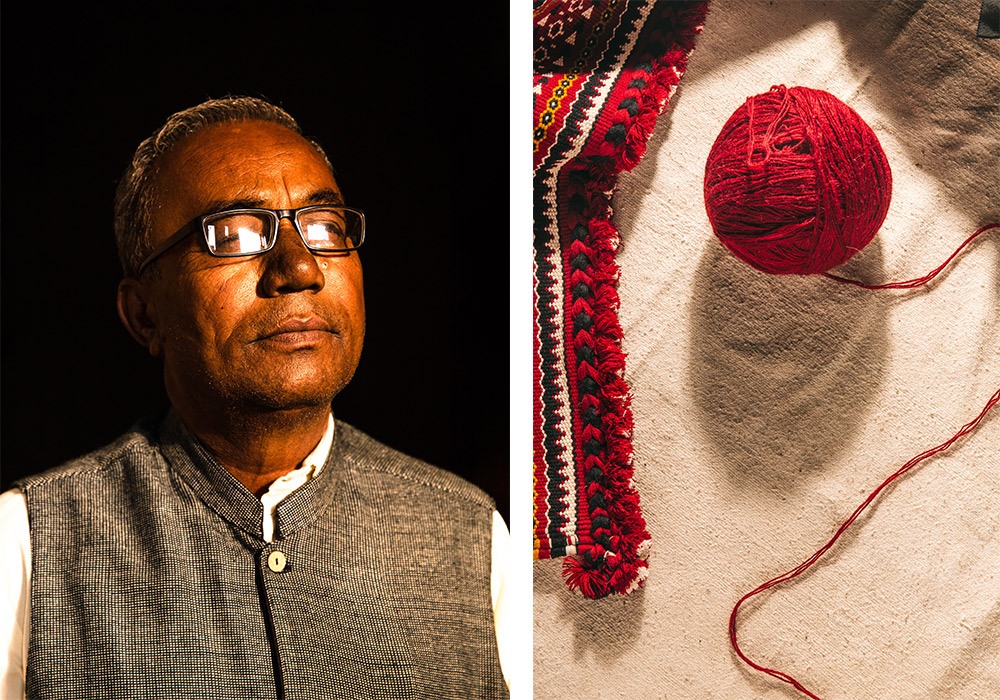

Vankar Virjibhai

Virjibhai is a weaver from Bhujodi, a village known for its textiles in Gujarat’s Kutch district. He has been weaving carpets for nearly 40 years, and is part of the fourth generation in his family to take up weaving. Back in the day, he recalls making rugs and blankets with his father for the Rabaris, a pastoral community indigenous to the region. “They gave us the wool and we made blankets for them. That was it, that was our trade,” he says.

Early on, his father trained him at the loom and insisted he work on weaving carpets. He had resisted at first because carpets are tougher to weave than rugs and blankets — the material is thicker, it takes immense concentration and time, and is done entirely by hand, without any tools. It can take anywhere between four days and a month to weave a carpet, depending on its size and design details. According to Virjibhai, to be a carpet weaver, one must possess a lot of discipline and determination. Even today, nothing can distract him when he is sitting at his loom. “I often forget to eat,” he laughs.

Sharing his knowledge is also something that gives him immense joy, he says. Virjibhai has held workshops and interacted with students from design schools like the National Institute of Fashion Technology in Gandhinagar. Intuition also plays a role in his day to day work — whether with picking the right clients or knowing when to stop. “Sometimes I just know that the carpet won’t get done on that particular day, and I ask my son and the karigar to take a break and start again tomorrow.” He doesn’t plan on passing on the baton anytime soon — retirement hasn’t crossed his mind — and he works as vigorously now as he did in his youth, even cheekily challenging his son to a race to see who finishes weaving a carpet first.

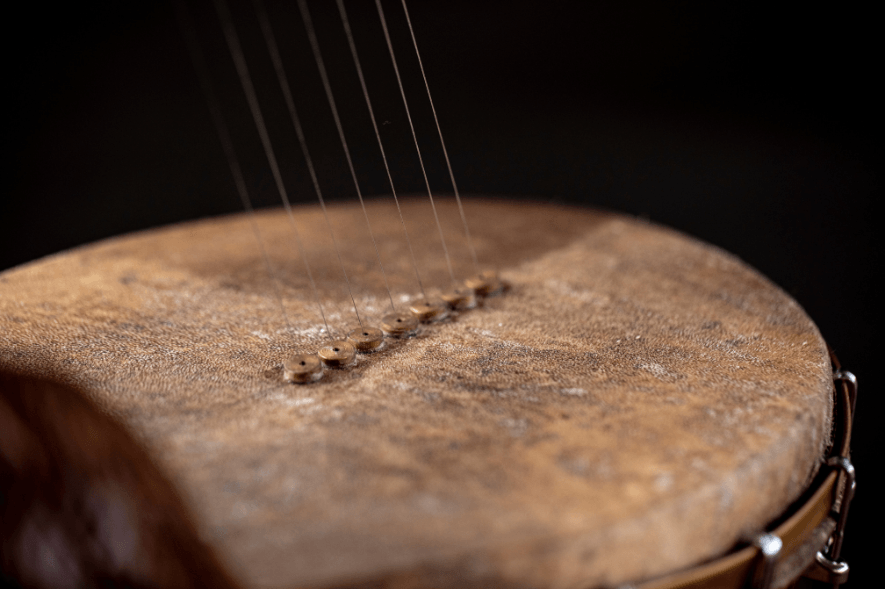

Ghanshyambhai Gajjar

Block-making is an underrated craft. It constitutes carving designs on blocks of teak wood (sagwan), which are later used to print on fabric. Ghanshyambhai is a block maker from Pethapur, a village near Gandhinagar in Gujarat. The craft has been in his family for five generations — he alone has been doing this for the last 35 years. What sets apart the Pethapur block from the Jaipur block — the Rajasthani city is also well known for the craft — is that their carvings are deeper and straight which makes their blocks last longer, Ghanshyambhai explains.

He chose to continue the family trade because it gave him the freedom to do things in his own time. “Rather than being tied to a job or doing something that would involve more labour, my family craft offered security as well as time to myself.” Ghanshyambhai not only whittles the wood into shape, he also draws the designs for his blocks. Over the years, the sort of designs in demand have changed. Earlier, there was a market for minute, detailed designs, like the Saudagiri print which would take around five to six days. Now, bigger, minimal, geometric patterns are in style, which can often be done in a couple of hours. Technology has affected him — both adversely and positively. While quicker, cheaper alternatives like screen-printing have somewhat reduced the demand for blocks, the internet has helped the artisan connect with a larger community and more clients.

Unlike the Bhujodi weavers however, the block makers of Pethapur aren’t encouraging their children to continue practising this craft, Ghanshyambhai tells us. All three of his children are either working or at university. “Block-making is intensive labour that doesn’t offer as much money as a job in the service sector, so we want them to study and have more options,” he says. And what of the craft, one might wonder. He continues to showcase his works at exhibitions around the world, hoping to make designers and design enthusiasts more aware of his craft. He also works with Design Mill, an Ahmedabad-based studio that is helping to bring block-making back into the spotlight.

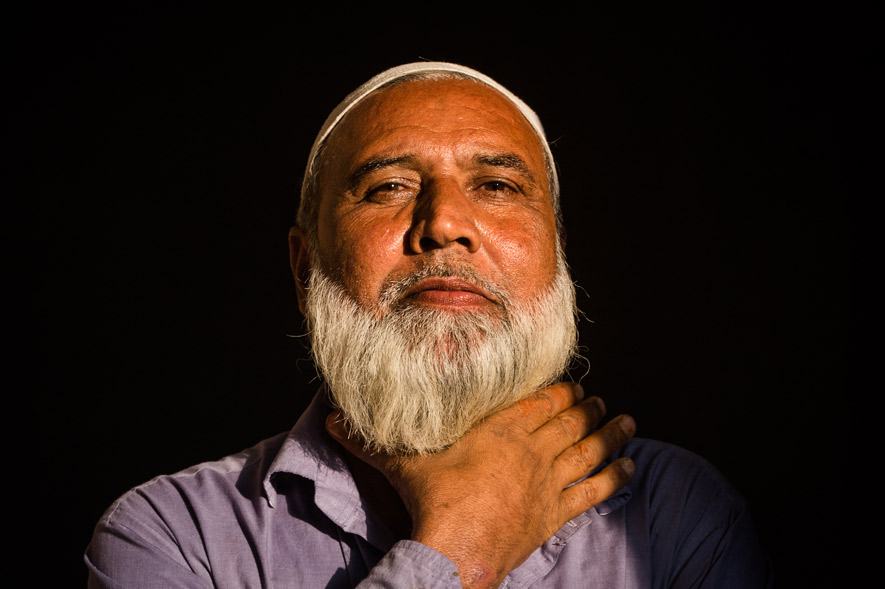

Ramzubhai

Ramzubhai is a potter from Bhuj in Kutch. He has been working with maati, Gujarati for mud, for around 32 years now. He can’t recall exactly when he picked up the craft, but remembers his grandfather teaching him to use the wheel as he was growing up. “All you need is mud, water and a wheel,” he says. “If you don’t have a wheel, your hands are enough. And then you need wood to bake the pot.” He makes the pottery process sound exceedingly simple, but in reality, it can take anywhere between two hours to eight days to finish a product, depending on its design and the kind of material used. While he used to primarily work with local mud found in Bhuj, over the years, he has been dabbling in ceramics as well, along with other kinds of mud.

It hasn’t always been pottery for Ramzubhai. He tells us about engaging with different kinds of trades on the side like farming and being a tailor for a bit too. “But maati is not an interest. I am deeply attached to it. I am in love with it. I will continue doing this till I die.”

Ramzubhai’s work involves interactions with contemporary designers — he works with Dehaati Design — but he’s a firm supporter of function over form. “In my opinion, the market needs something new every five years, and so a design trend becomes obsolete after that time.” When it comes to his products, he claims that they have very little to do with these sort of trends. “We are tied to local communities, like the Gadhvis and the Rabbaris, and their traditions. They support us and that is why our craft isn’t affected by what’s in style,” he says.

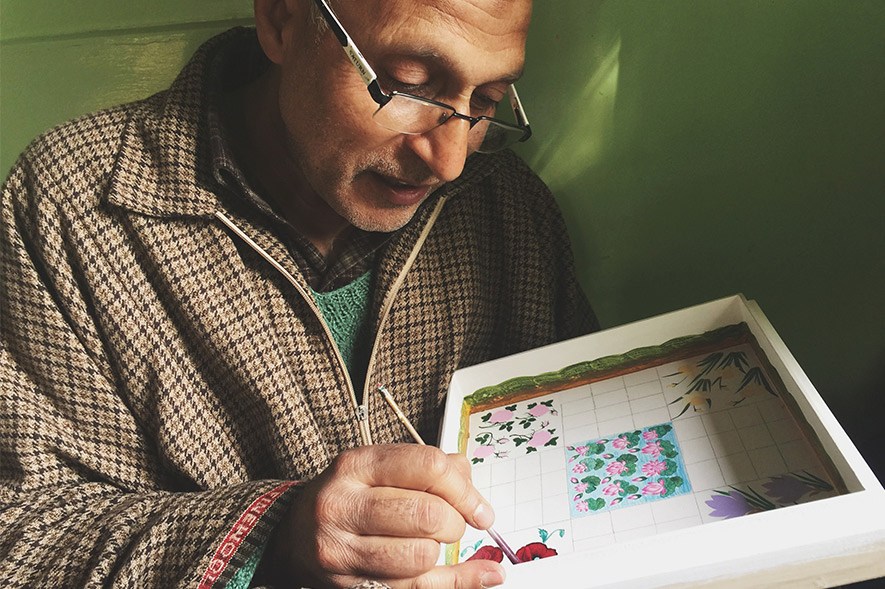

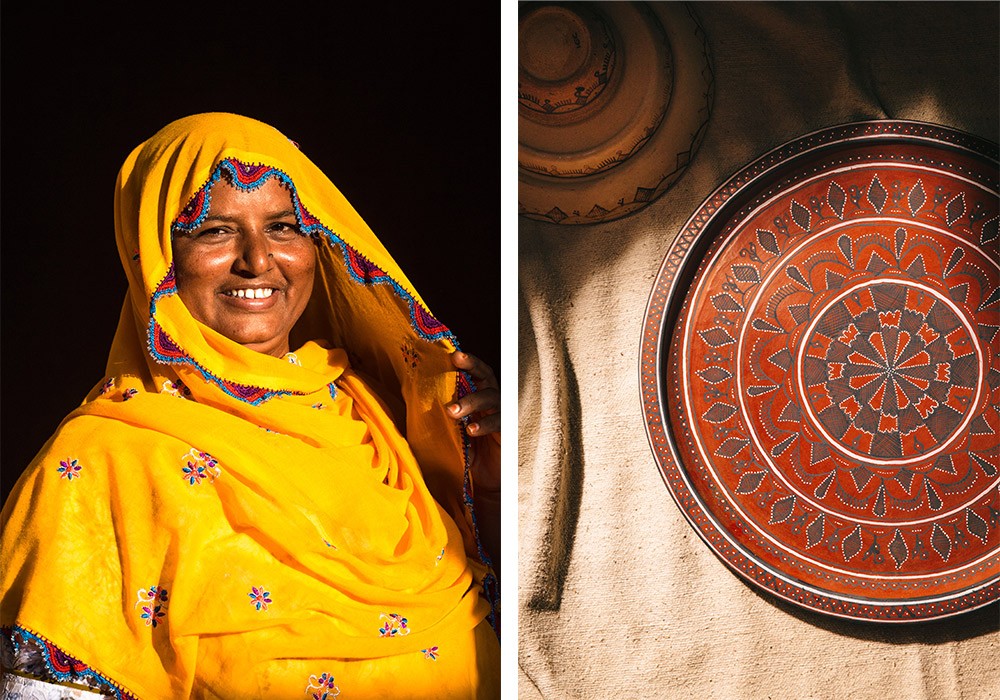

Jainaben

Jainaben is a painter of earthen pots, plates and other objects from Bhuj, Kutch. She uses paints that are completely natural, made from rocks brought from the wild, and her brushes are slender bamboo sticks with frayed ends.

Jainaben is Ramzubhai’s sister, and like him, doesn’t really remember when she started painting earthenware. “I’ve been doing this for as long as I can remember. I was very little when I learnt how to do it,” she says. She paints the pots, plates, cups, and other products made by her brother and other potters in the family. Some typical motifs used in Kutchi pot painting are geometric patterns like the double vajero (resembling the teeth of a comb) or criss-crosses, which are Jainaben’s favourite, along with fauna like scorpions and large ants.

Like her brother, Jainaben has had other interests too. She worked with the tie-dye form of bandhani for a few years but came back to painting. A love for painting runs in the family, she says proudly. Her two-year-old grand-niece is also already painting pots. “We teach our kids from a very young age,” she explains.

Vankar Murjibhai

Murjibhai is a weaver from the Kutchi village of Bhujodi. He has spent decades honing his craft, one that has been practiced for generations within his family.

What sets the Bhujodi weaves apart is the extra warp they use to weave in their traditional motifs — geometrical patterns like wankiyon (zig-zag patterns), chomukh, huthdi, and nature-inspired symbols like the popat and mor. He’s focused on maintaining the essence of this traditional craft, which means he’s also mindful of not straying too far from the original design or chasing trends. An expert at weaving shawls, dupattas, and saris, Murjibhai believes that to truly master the craft, one must know how to dye (a strenuous task, according to him) in addition to weaving.

He remembers being in his early 20s when, right after clearing his SSC board exams, his father sat him down at the loom. “My skill lies in my hands, not my brain,” he says. But his education has helped him step out of his tiny community and engage with designers outside. These interactions have encouraged him to experiment more and hold design thinking at the core of his craft. Quoting Kabir’s dohas, which he believes perfectly sum up the philosophy of Bhujodi weavers, he says that their community is one where artisans support each other, and where their craft is treated as religion. He is hopeful that as their weaves reach more people through platforms like Raw Collaborative, their craft and trade will continue to thrive, keeping them independent and self-sustained.

Raw Collaborative 3 took place at the Mill Owners’ Association Building in Ahmedabad, from November 28 to December 1, 2019.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.