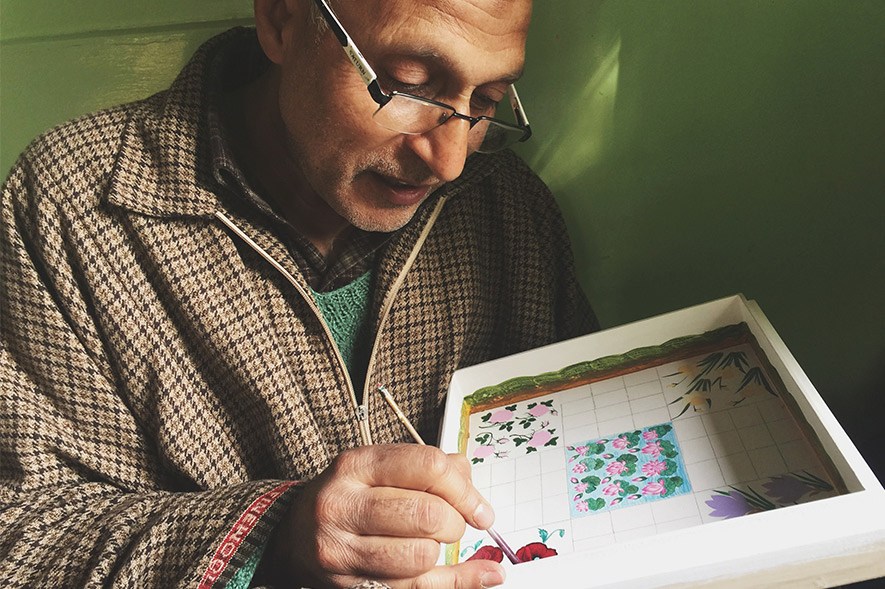

In such ugly times, the only true protest is beauty.” It’s a quote credited to American singer-songwriter Phil Ochs, and it’s what designer Harpreet Padam and the Kashmiri Naqqashi artisans engraved, in braille, on paper mache coasters. These artisans from the Naqqashi community are known for their detailed paintings on paper mache. “We had these discussions with the artisans about the best form of protest an artisan can have, and it comes down to the fact that you must work more at producing these objects of beauty that you continuously have been for so long — that’s your way of protesting. You needn’t be the one who picks up a rock and starts hurling it at the army,” Padam explains.

Over the last few years, Padam has worked extensively with crafts communities across India, having these conversations and collaborating on contemporary products. His work with the Naqqashi community was commissioned by Commitment to Kashmir, a trust which aims to empower a new generation of craftspersons to become independent and sustainable craft entrepreneurs.

New Delhi–based Padam, who studied accessory design at the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), launched Unlike Design Co. with graphic designer Lavanya Asthana. At the studio, the two work on packaging, branding, and accessory design projects. It’s Unlike Design Co. that runs towithfrom, an online retail space that showcases objects created by the design duo as well as the products from Padam’s work with artisans.

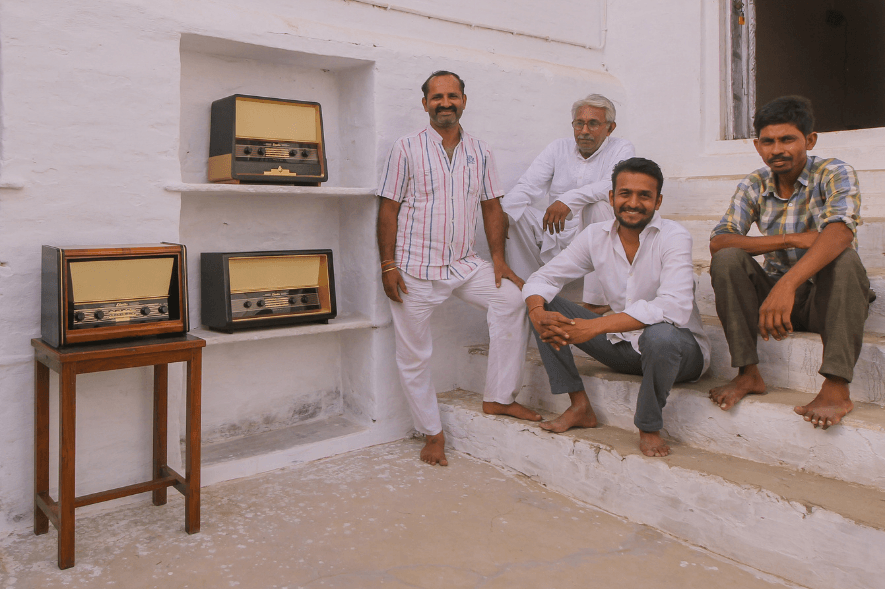

In the crafts sector, Padam has been working with organisations like Commitment to Kashmir as well as on government projects. “The government’s Ministry of Minority Affairs and NIFT together operate a scheme called USTTAD, which is essentially for the upgradation of skills of artisans in various minority communities across India,” he explains. USTTAD literally stands for ‘Upgrading the Skills and Training in Traditional Arts / Crafts for Development’. It’s this scheme that has seen Padam travel to various parts of the country to conduct workshops with craftspeople who do Bidri work in Bidar, Karnataka and with skilled wooden cutlery makers in Udayagiri, Andhra Pradesh.

Padam’s favourite USTTAD project was his first, with the crafts community in Bidar. Working with Bidriware entails finding the right kind of soil, which is boiled in water, turning an absolutely chrome coloured product into jet black within seconds, he explains. “To watch that happen is a beautiful process.” The resultant products from his workshop with the community in Bidar, include beautiful trays, boxes and paperweights, available on the towithfrom website. In fact, the platform has often been the first consumer for products created with other artisans as well — which also reinforces a sense of confidence in these artisans.

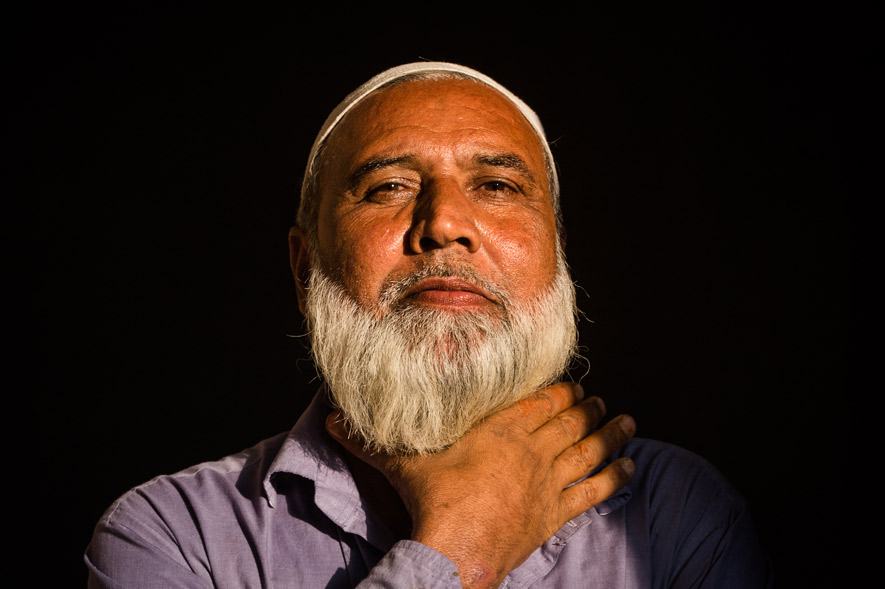

For the Commitment to Kashmir projects, Padam travelled to Srinagar to work with artisans from various communities — like the Naqqashi people, who paint paper mache, and the Sakhtas, who make the paper mache forms and structures, along with walnut wood carvers and crewel embroiderers.

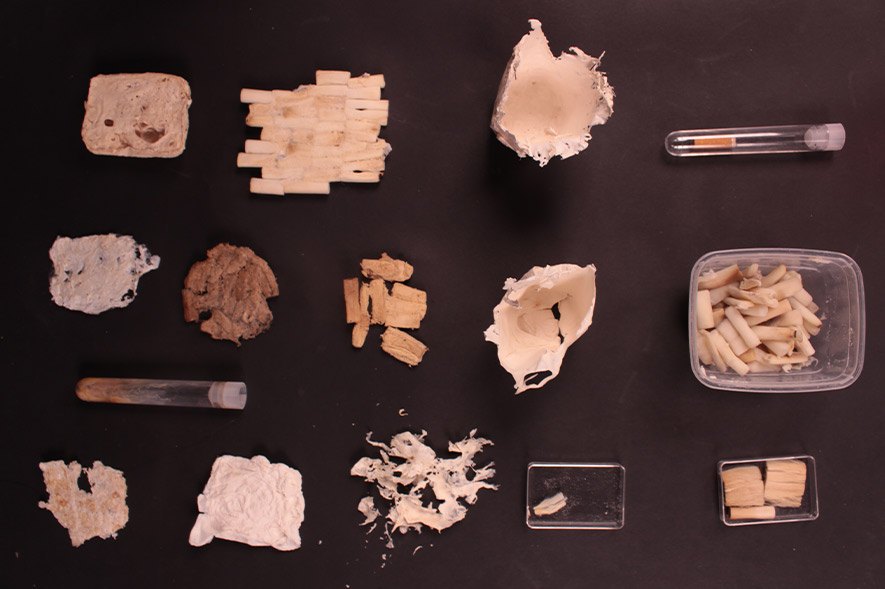

With the paper mache artists, “what has been happening traditionally is that it is the Naqqashis who take full credit for the product, although their contribution is [only] 50 per cent. The person who actually generates the structure and the form itself doesn’t really get too much credit and has always been in the background,” Padam explains. “So one of the objectives of the project was to make [the Sakhtas] independent as entrepreneurs so that they are the ones who actually finish the product at their level and bill it to consumers.”

To do this, he worked with the moulds they already had, but used local materials like charcoal and turmeric to colour the paper pulp and give it a raw, finished look. The pulp was then used to make boxes and bowls, grey on the outside and yellow on the inside. These products have been in development for a while, and finally came together during Padam’s last workshop with the Sakhtas around July, right before the now-two-month crisis in Kashmir.

With the Naqqashis, Padam developed new designs for pencil cases, small jewellery boxes, photo frames, bowls and trays. “The objective was that since these are fine artists, what they paint is what the product is. I thought, in some way, since they had the capability to produce any sort of artwork with their brushes and paints, they should actually be sending out some sort of messages about what they feel about being in Kashmir,” he says. “There is a lot of frustration and depression about being in a place like Srinagar, which is always surrounded by the army. It’s been going on for so long that there’s a faint sort of numbness that’s come about.” Conversations with the artisans are filled with subtle undertones of mainland India as an oppressor, yet their paintings depict flowers, trees and other happier themes.

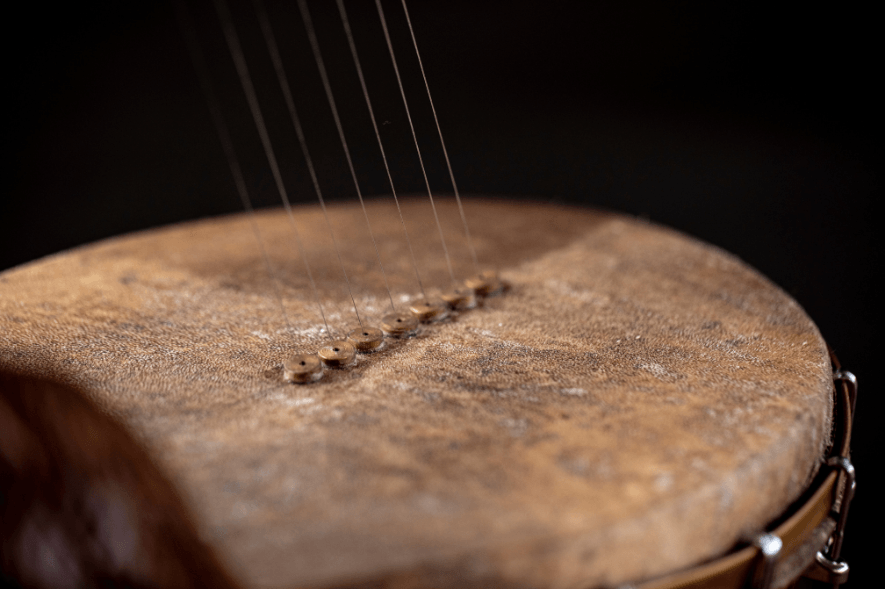

Ultimately, Padam worked to create three kinds of stationery boxes with the Naqqashis. The first kind has flowers at one edge and on the other, a particular razor wire that’s used in Srinagar, “which is much worse than barbed wire, and tends to signify the army.” For the second, Padam juxtaposed the Indian Army’s camouflage pattern with a screenshot of Srinagar from Google Maps. The third box involved relief work — “they do these raised effects where you can actually touch and feel the texture” — of an apple and rocks. The idea was to “contrast how the place is [traditionally] known for its apple orchards but at the same time it has its new identity of rocks being thrown at each other.”

While these products have been months — if not more — in the making, the themes they deal with are more relevant than ever today. Apart from a few calls, Padam hasn’t been able to be in contact with the artisans since the lockdown was imposed. “They resist speaking of any local situation since they’ve been strictly asked not to talk of it,” he says.

Padam doesn’t get to choose where he goes next. But if there was one crafts community he could work with across India? “I would like to work with a carpet-weaving community, either in Rajasthan or the ones in Uttar Pradesh,” he says — he has no idea how exactly that would happen, but he’s full of hope.

Towithfrom stocks many of the products mentioned in this piece. See the collection here.

Fabiola Monteiro is Senior Editor at Paper Planes. She’s on Instagram at @fabiolamonteiro and on Twitter at @thefabmonteiro.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.