India’s 7,516km–long coastline is dotted with scores of tall, swaying coconut trees. According to reports from 2018, the country is the world’s third largest producer of coconuts. While the mature coconut is used for its coir, oil, milk and meat, the young, green tender coconuts are a mainstay on street corners across towns and cities in coastal India, beloved for their cool, refreshing water and their fresh, wiggly malai. There’s no dearth of use of the coconut — but it is the water from the mature coconuts that forms the basis of a new biocomposite material (also called malai) that is a PETA-certified alternative to leather.

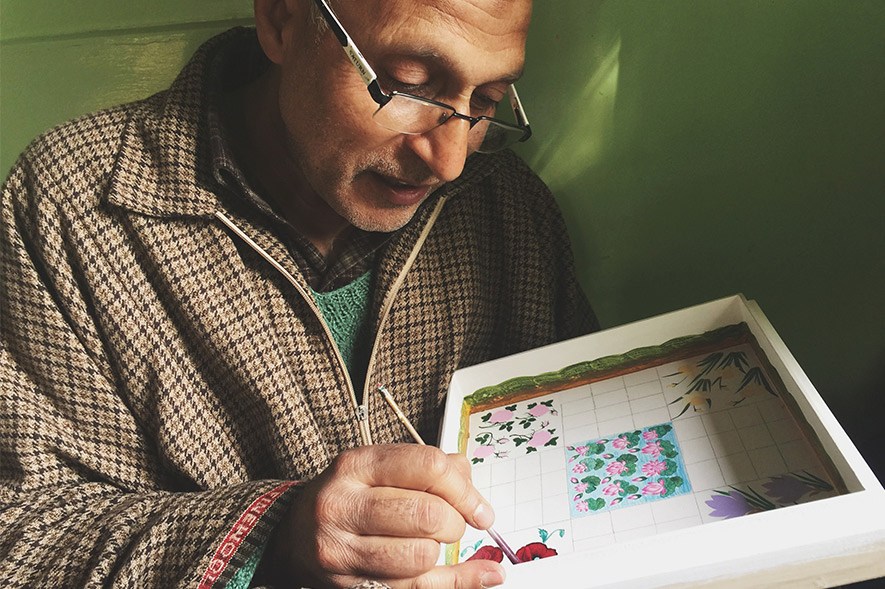

Designer Zuzana Gombosova, who co-founded Malai, the start-up behind the material, studied textile and fashion design, followed by an MA in Material Futures at Central Saint Martin College of Art and Design in London. The course led her to insights on circular design and sustainable design processes, and the importance of materials in design. “That’s also the first time I encountered bacterial cellulose, which is currently the main ingredient of the biocomposite material that malai constitutes,” she explains.

About five years ago, Gombosova — who hails from Slovakia — moved to India to work for an Indian manufacturing company, where a research project on waste in manufacturing spurred her to examine materials that were truly circular. “From my research [during my MA], I knew that bacterial cellulose can be produced from mature coconuts — there is an existing industry in the Philippines where it is grown for use in the food industry — so I was interested in exploring this material here in India.”

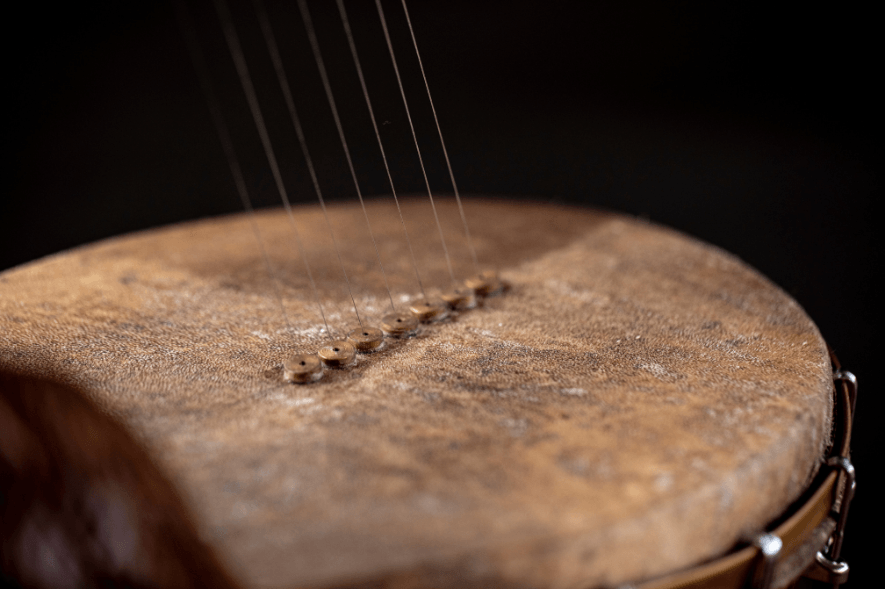

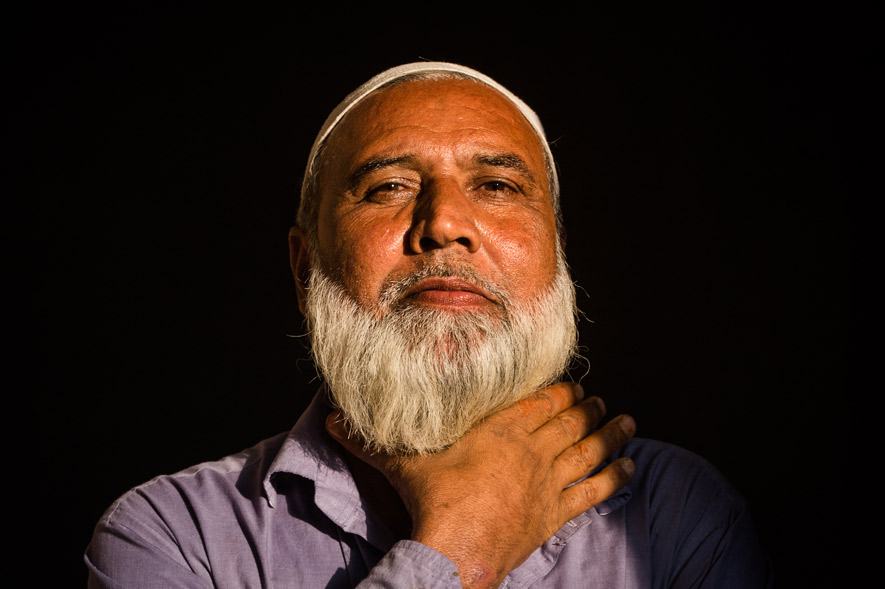

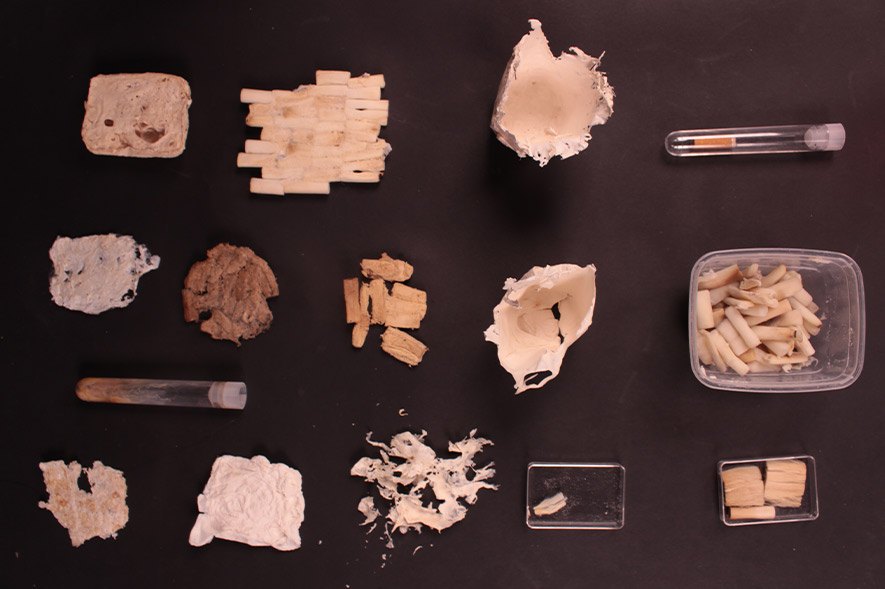

For this, Gombosova partnered with Susmith CS, a product designer from Kerala, who was also very keen on exploring this material. “Our drive was to develop a material that would be based on bacterial cellulose but would have all the properties necessary [for use] in commercial products,” Gombosova explains. In 2017, the two moved to Channapatna in Karnataka to begin their research. Along with the gelatinous bacterial cellulose cultivated in coconut water, they incorporated other natural materials like fibre from banana stem and hemp fibre to make it strong and sturdy. After about seven months of primary research, they had a product that resembled leather.

The duo then moved camp to Kerala and set up a pilot production unit near Kochi, slowly increasing the size of their sample sheets, improving production technology, and building their local supply chain. The production cycle takes about four weeks. First, waste coconut water is collected and fermented to grow bacterial cellulose. Then, the cellulose, along with the natural fibres, is processed into sheets, which are dried, mechanically softened and coated. While the material has been well received by the design community — both internationally and in India — Malai’s set-up is still small. “We can produce around 200 square meters per month,” Gombosova says.

Over the last two years, Malai has been supplying sheets of the material to fashion brands, manufacturers and designers who have been actively looking for sustainable replacements to animal leather. “I always say we were kind of lucky to be in the right place at the right time, because the attention of many industries, predominantly the fashion industry, has shifted towards sustainable materials in the past couple of years,” Gombosova explains. Gombosova and Susmith have also been tinkering with the material at their own design studio at Malai. In February 2020, they presented a collection of their accessories at the Lakmé Fashion Week and won the Circular Design Award. As part of the award, they will present another collection digitally in October.

Currently, malai is predominantly being used to create fashion accessories and footwear. But Gombosova says that they are in their second stage of research to improve some of the mechanical properties of the material, which will make it more suitable to be used in interior design — as panels, wall coverings, and upholstery for furniture — and in stationery.

Now, more than ever, we need designers and design thinkers to find solutions that not only do good, but also attempt to fix the harm that has already been done. As for how else malai could be used? For Gombosova, “imagination is the only limitation.”

Learn more about Malai here.

Jessica Jani was formerly part of the editorial team at Paper Planes. Find her on Twitter at @_jesthetic.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.