This story is part of Issue #3 of Big Little Things, a limited-edition magazine, produced and published by Paper Planes for UnLtd India, a launchpad for early-stage social entrepreneurs. Read more about this collaboration and UnLtd India here.

I was twelve when my father retired from the Indian Air Force in 1992. My family’s nomadic life, which basically meant moving cities every four or five years, and a life in which I arrived fairly late, came to an end. When we weren’t moving cities, we were moving houses within the same Air Force Station. This feeling of being in a temporary home has a wonderfully efficient effect on the amount and quality of objects and possessions that one keeps and moves on with.

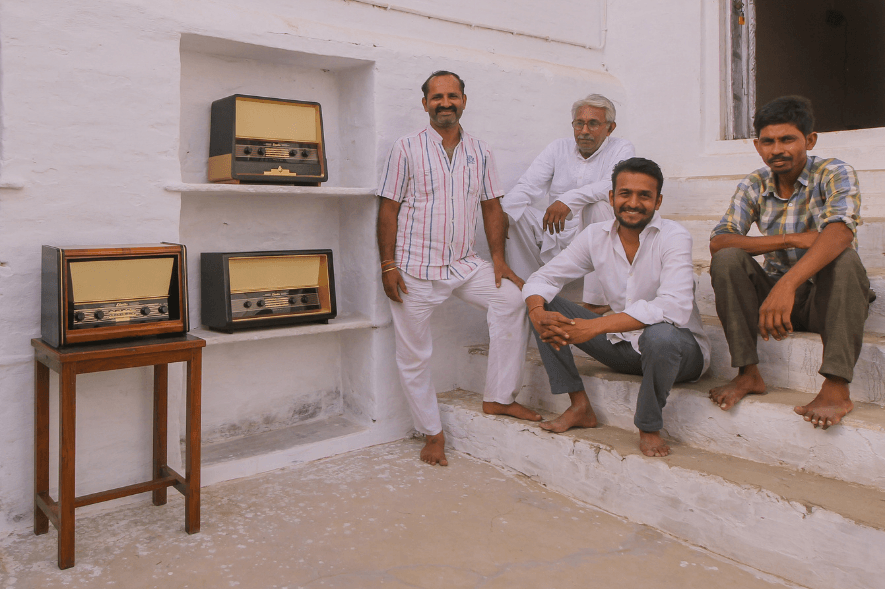

It did not take me long to realise that some of the most cherished objects my mother never discarded on our postings were attached to stories of where, when and from whom they were acquired. It was the same with all the other families — their homes, lobbies, porches, drawing rooms, bedrooms, kitchens, all filled with objects of significance — whether functioning as decoration or in regular daily usage. Each home a unique museum of things collected over distinctly different career trajectories across the country’s cities and towns. Mortar-pestles from Rajasthan, mirrored wall hangings from Gujarat, sea-shell curtains from Goa, striped coir doormats from Kerala, carved wooden tables from Uttar Pradesh, embroidered bedsheets from Punjab, macramé lampshades from Pune, Maharashtra, and strange combinations of so much more — all existing in unique congruous harmony. Everything so collectively out of place at once that it belonged together for the very same reason. As I grew into the culture of definitions, in hindsight, I realised these were all craft objects.

When we eventually settled at our relatively permanent home in Chandigarh, the insatiable urge to discover and acquire more craft objects for the home surged, perhaps this time without the fear of living in excess. Accompanying my mother, it is at this time that I started visiting craft emporiums in the city and understood that they were places where one could still access signature goods from the states of India — like the Gurjari store that represented Gujarat, or Phulkari, which stocked handlooms and handicrafts from Punjab. Of course, there were also the travelling melas and bazaars which, honestly, I found a little more exciting, maybe because there was a ‘limited-availability’ pleasure related to both bazaars as well as craft objects. And then there were the Kashmiri carpet and shawl sellers, pedalling through neighbourhoods on their cycle rickshaws, happy to unroll dozens of carpets at the faintest sign of interest.

When I moved away to design school, I lost touch with these shopping pleasures. Luckily, what I gained instead was a direct introduction to craft and craftspeople — the hands, faces and first-person stories behind the veils of marketplaces. As time passed and the millennium changed over, I occasionally visited the craft stores and state craft emporiums at Delhi’s Baba Kharak Singh Marg, sometimes for research into the making cultures of a state and at other moments, to find unique handmade gifts for friends. But something had changed, or perhaps not. The emporiums had collectively and consistently frozen in time. The potential craft buyer had moved on to newer, well-lit, thoughtfully designed store environments — often gift shops that did not see much benefit in being solely dedicated to one of India’s states or to handmade objects. I remember Taj Khazana in Bombay, The Box @ The Park, The Bombay Store and Cinnamon in Bangalore, Amethyst in Chennai, The Home Store and Good Earth in Delhi, and Fabindia taking up the role of the new emporiums. But there were still exceptions.

At one of Delhi’s busiest traffic intersections, Dilli Haat provided a refreshing experience. An organised open-air shopping plaza with booths for craftspeople where they could set up shop for a limited time. Once the shopping was done, visitors could fuel up at cafes organised by various states. Dilli Haat was the bazaar and the emporium, all in one, with food as an added attraction. It was then, in those early 2000s, that I realised — thanks to Dilli Haat — that food and craft objects were not different. They were both ingrained with similar making traditions and values. The annual Surajkund Mela — when a huge parcel of land on Delhi’s border became the camping ground for craftspeople from all over India for a few weeks — was another organised setting for craft, food, and additionally, performance. There were dances, puppet shows and craft demonstrations.

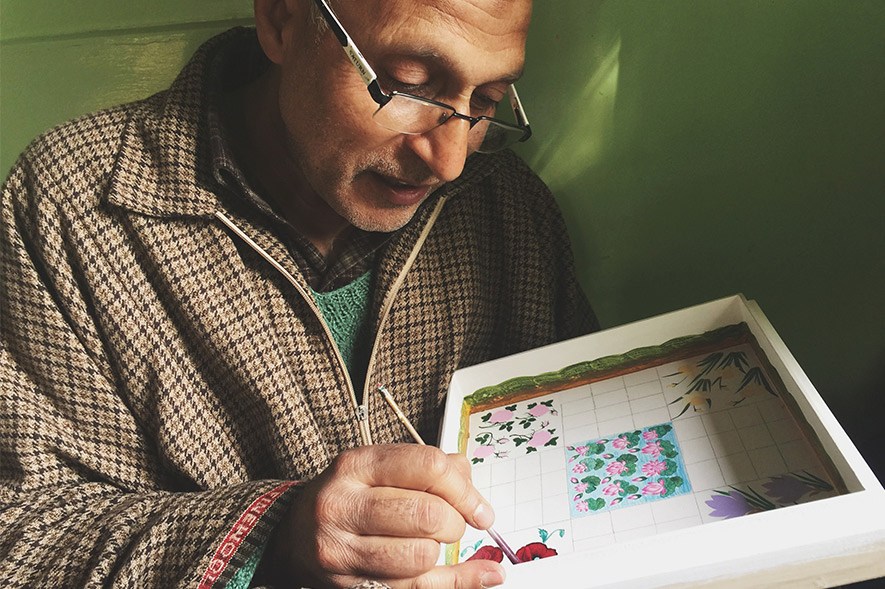

As I noticed the selling environment for craft objects undergoing changes, the objects themselves did not stay unchanged. Looking back, what I remember most of that time, barely two decades ago, was the quiet servitude that was ingrained into crafts and the way they were perceived by people who bought them. Maybe what I mean to say, on a positive note, is that they weren’t always perceived to be as special as they somehow are today. They functioned well, were made well, and were valued greatly on the merit of that very functional efficiency, which was more if not equal to the significance of their culture and place of origin. It was a time when the terms ‘handmade’ and ‘craft’ were not overemployed and didn’t overshadow poor workmanship. A handmade marble agarbatti stand, for example, with a circular array of five holes to hold the incense sticks, would manifest the maker’s time and the attention given to space the holes roughly at 72º from each other. The technology, cost and accessibility of a geometric compass that can facilitate this little task has only improved over the years, yet the discipline and attention that the act deserves is getting harder to spot. This is compounded by the forgiving nature of the buyer, who is increasingly accepting of lesser quality.

Today, one is usually at a loss when it comes to figuring out what the best place is to buy craft — there are, in a sense, more avenues than there have ever been, and yet there are very few. The emporiums at Delhi’s Baba Kharak Singh Marg are still surviving, perhaps on mandatory state budgets more than consumer sales. Amongst them are subtle contrasts — like Delhi Craft Council’s Kamala Shop, an example of what the emporiums can at their least transition to but perhaps never will. The quality of products available at Kamala, along with their presentation and packaging, is noticeably superior to the emporiums. Of course, one may also find some hidden treasures within state emporiums, but not without a good amount of patience and persistence to explore the dark, musty environments. At Dilli Haat too, one can now feel a sense of stagnation — the craftspeople who exhibit their wares are seldom the makers themselves. The products themselves are often plastic-wrapped imports, cheaply made industrial goods polished off to somehow qualify as craft, if only visually. The Surajkund Mela still arrives in the late Delhi winter and receives more visitors than ever before, but well-made handcrafted goods are few and hard to find. The only open-air space where I can still hope to access good makers and their work is perhaps the monthly bazaars organised by Dastkar at their Kisan Haat campus in South Delhi’s Andheria Morh.

Good alternatives to all the physical stores are the tens of web stores devoted to craft. But how does one reach them? Perhaps as recommendations from others who have bought, depending on how their experience has been. There are no giants in the field, and everyone has their own favourites. This very ambiguity of a dependable source of well-made craft objects is a problem plaguing craft and the craftsperson. The good craftsperson still exists, but how does one reach him or her? And how do they reach us? Who can even provide an authentic recommendation? Whom does one trust? Of course, for those in the know, there are excellent stores and sources for skilfully constructed products, but when did the availability of good craft objects become a subject of knowledge for those in the know? And above all, how is it that craft has become so distanced that it is not all around? When did it leave the local market and resign itself to a special corner? Most importantly, who decides what is well made? The craftsperson continues to make, without pondering over these larger questions that may eventually make a difference to their livelihood. One could say that as any phenomena too large for one person alone to address, in this case too, the best would be for each concerned to play their role well. But that may not be enough.

The solution may lie in the creation of a good representative model that works not only for connecting craft to people but also demonstrates concern for the larger direction in which things are moving. I strongly believe that a new retail model will do the needful, for craft benefits best when it connects makers to buyers. By working example — not by policy, law or scheme. There is little hope or expectation of the government leading the way — less trust, too, when its intent directly reflects from acts such as the recent abolishing of the All India Handloom Board as well as the All India Handicrafts Board of India.

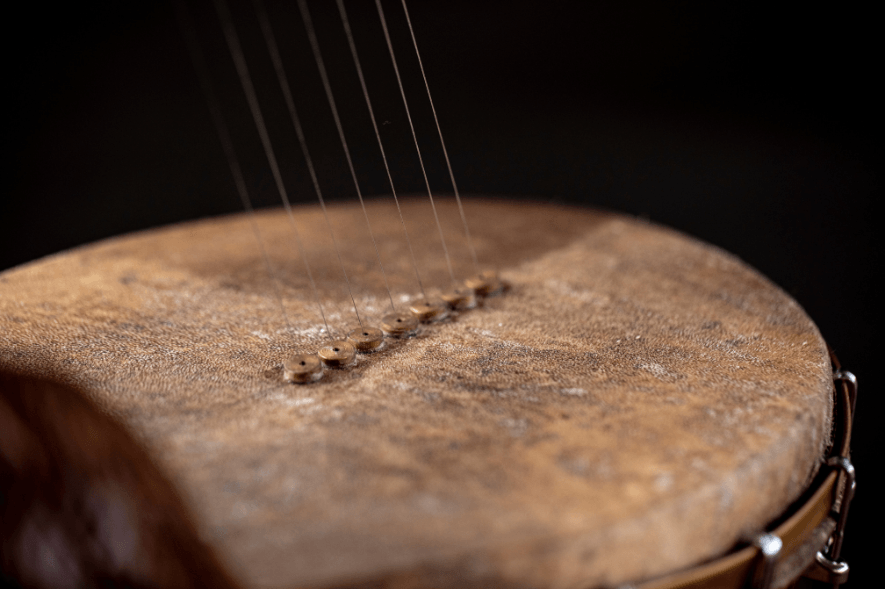

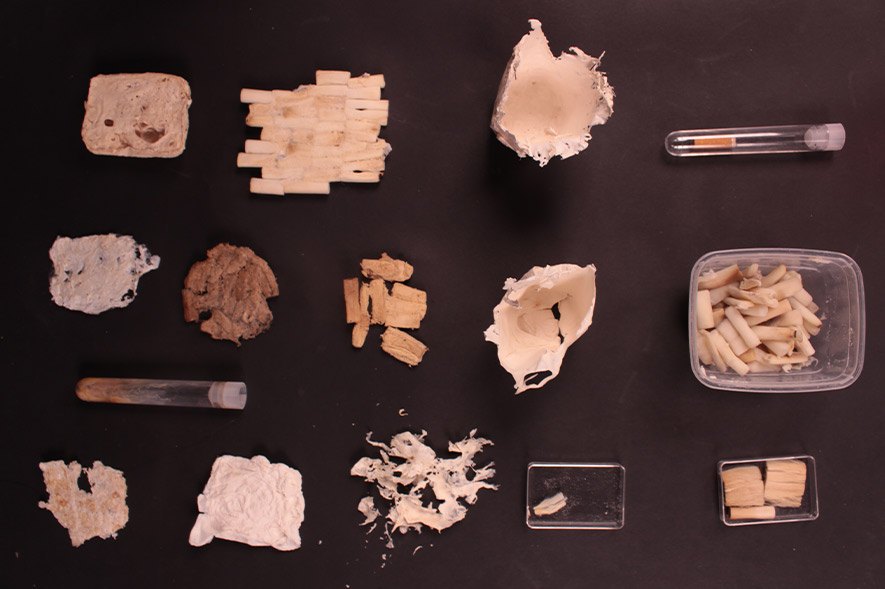

Beyond the marketplace for craft, beyond the skill of the maker, and even beyond the quality of what is made is another crucial factor, that of the definition of what qualifies as craft in the first place. As a country, we have many making traditions that qualify, even if in a very broad definition, as craft. It is perhaps the very need to define that poses a big threat to our intrinsic Indian way of being.

The government’s supposedly well-meaning initiatives to classify certain making cultures as ‘craft’ and not the others have unfortunately led to an all-forgiving sanctuary for recognised crafts. This certification approach indeed helps many, but also ironically ignores making skills that retain higher values of being craft in the true everyday utility sense. A certified pashmina shawl sold in a clean, urban retail environment is no more craft than say, an achappam (rose cookie) maker sold by the side of a noisy, dusty road at a weekly haat. Nomadic blacksmiths, brick makers, basket makers, cobblers, broom makers, vessel repairmen, sign painters and rickshaw decorators may never stand a chance to gain from government schemes and incentives. In my opinion, as grey-area craftspeople, they all suffer from the evils of terminologies, classifications and certifications. Not that they actively seek the government’s recognition, but what is lost is a potential sense of self-worth and esteem in one’s making skill.

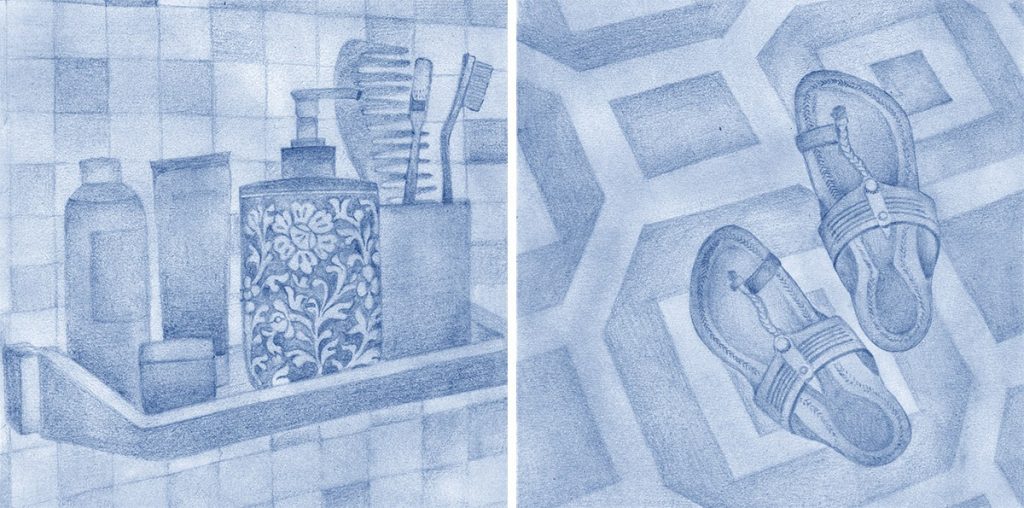

The other key difference between grey-area crafts and labelled crafts is the growing tendency of the latter to aspire towards being showcased rather than being used and celebrated through that very use every day. Grey-area crafts are mostly everyday objects that serve their purpose silently, efficiently and well. They may be admired for their visual aesthetic and detailing as well, but this aspect is never at the cost or excuse of their being handmade. Decoration itself is a softer and high form of function resting upon the need for self-actualisation, which is born of deeply innate sophisticated acts such as ornamentation, dress, dance, ritual and such. Even from the customer’s perspective, one is more likely to forgive a defect or inconsistency in a ‘craft’ product bought from an emporium than in a broom bought from the local store. The result of this phenomena, both at the makers’ end and the buyers’, is that craft products are moving away towards a premium access-only environment where prices are high and important factors like quality and efficiency of use are being masked behind their formal craft certification, accorded by the marketplace it is sold in as well as the government’s effort to promote it. It is as though craft, unable to (or believing that it didn’t even need to) compete with industrially manufactured goods, has conveniently edged out a hazardous corner for itself.

The future of the craft marketplace likely lies in how the equilibrium between the authentic maker and the buyer is achieved. Undoubtedly, the making will not stop — things will continue to be made, in older or newer ways. Quality, authenticity and provenance shall continue to be judged. The true picture shall perhaps reflect best within our own lives and homes. It only takes a minute to look around to understand what I mean. What are the things around us that carry honest evidence of the soul of their maker? Or like my mother would have said, what shall we carry with us to our next home?

Read more about Big Little Things here.

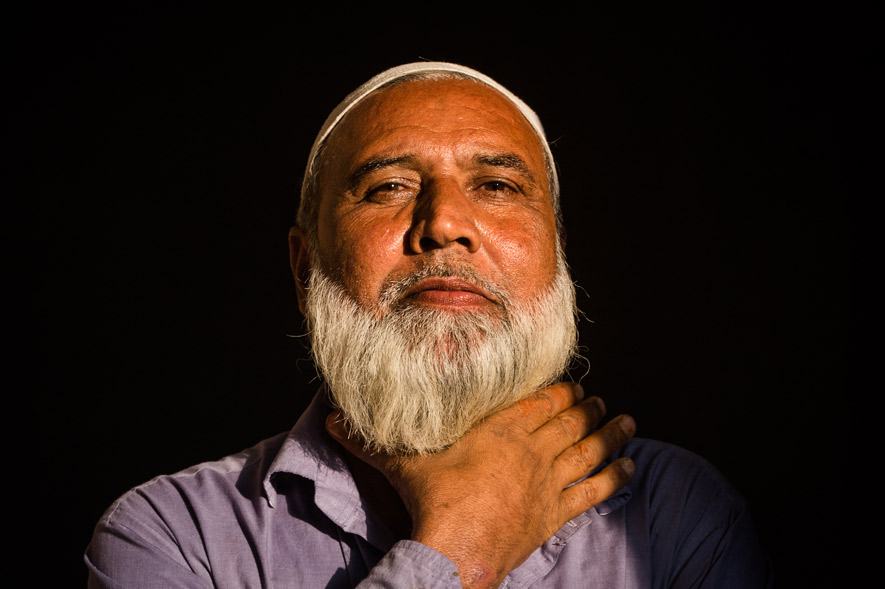

Harpreet Padam is an accessory designer, a partner at his studio Unlike Design Co. and co-founder of craft products brand TOWITHFROM. He occasionally teaches design at centres of the National Institute of Fashion Technology. He’s on Instagram at @generalaesthetic.

Tosha Jagad is a designer and illustrator, based in Mumbai. She enjoys working on projects with an Indian narrative and, of late, has been experimenting with pencil and carbon paper as a medium. She’s on Instagram at @toshajagad.

Tell us what you think? Drop us a line.